Lightning blasted his shoes off — and illuminated a pattern of abuse by staff

This article and others in this series were produced as part of a project for the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism’s National Fellowship, in conjunction with the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

Powerful lawmaker calls for juvenile justice review in wake of Herald series

At this juvenile justice program, staffers set up fights — and then bet on them

Dark secrets of Florida juvenile justice: ‘honey-bun hits,’ illicit sex, cover-ups

FIGHTCLUB: A Miami Herald investigation into Florida’s juvenile justice system

Keyon Felder’s right shoe bears witness to his near-deadly encounter with lightning on the roof of a building at Okeechobee Youth Development Center. Florida Department of Juvenile Justice

By Carol Marbin Miller and Audra D.S. Burch

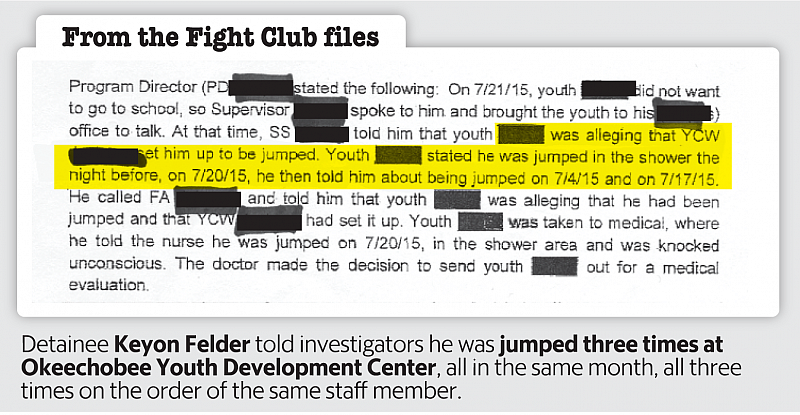

For two days, Keyon Felder begged a half-dozen youth care workers to protect him from his tormenter, someone he accused of orchestrating three attacks by other teens — the last of which knocked him out, and injured his face, head, arms, legs, chest and back.

The man allegedly engineering the attacks: one of their colleagues.

Keyon, 18, but an unimposing five-foot-seven and 140 pounds, told investigators he waited for some sign that his complaints were being addressed. Nothing.

On the third day, weary of being jumped and tired of being ignored, Keyon climbed a chain-link fence and hopped over a ring of razor wire onto the roof of the Okeechobee Youth Development Center schoolhouse as it began to rain.

He got his sign: The sky exploded.

Keyon didn’t know it at the time, but the roof was struck by lightning. He could taste blood, which poured from his eyes, ears, nose and mouth. The strike blasted the scorched sneakers off his feet. He could smell the burnt rubber. He could not feel his arms and legs.

“It just went dark,” he told the Miami Herald. “I’m just lucky, because it could have been worse.”

Almost three weeks after he was airlifted to the hospital on July 23, 2015, with hearing loss, Keyon told his story again, this time to state juvenile justice investigators. He told them he’d been “jumped” in the shower by two boys, leaving him nauseous, with throbbing headaches. He told them it was the third time he’d been ambushed.

He told them all three attacks had been arranged by one of the men paid to look after his safety. And he told them that no one would listen.

“There were things going on that the facility was trying to cover up,” he said.

Investigators have heard similar horror stories: From St. Augustine to Fort Myers, from Tampa to Miami, youths in state custody have complained that staffers are turning troubled kids into enforcers. The reward for a beating can range from Snickers bars and fast food hamburgers to Chinese combos and pizza. Even expensive sneakers.

The most iconic compensation: the humble honey bun, the cheap glazed treat that is currency in jails, prisons and detention centers throughout the state.

The practice has its own nomenclature: Youth workers offer “bounties” for assaults. The target of a bounty has a “honey bun on his head.” The victim has been “honey-bunned,” the object of a “honey-bun hit.”

Youths, including one at Okeechobee — where a handful of juvenile justice facilities are located — have also reported staff using the cue “30 seconds,” which means: I’ll turn my back that long while you beat somebody up. At Palm Beach Juvenile Correctional Facility, detainees said staff would yell “youth support!” to summon an enforcer, and tell teens they could release the “pressure on their chest” by decking a peer.

An officer examines the rooftop where Keyon Felder took refuge at Okeechobee Youth Development Center. Florida Department of Juvenile Justice

A youth care worker at Palm Beach Correctional confirmed the practice in a court declaration in August 2012: “In order to increase the ability to control the facility,” Tina Folger wrote, “youth would be used to control other youth.”

An examination of 10 years of Department of Juvenile Justice records reveals a trail of incident reports, almost like bread crumbs, leading to the conclusion that staffers at some institutions foster a culture of brutality-by-proxy. What is not in the records is any sort of acknowledgment that the problem might be systemic — nor any directive saying it must stop.

Paul DeMuro, a retired juvenile justice administrator who worked as a court-appointed watchdog in Florida following a federal lawsuit over shameful conditions, said kids get turned into enforcers in systems where casual violence festers over a series of years.

“Unless you really get to the heart of the damn thing, it will reassert itself,” DeMuro said

“Yeah, you need new policies. Yeah, you need honest monitors,” he added. “It’s necessary, but it’s not sufficient.”

Jeffrey Butts is director of the Research and Evaluation Center at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, and he’s worked with policymakers in 28 states, largely on youth justice.

“It takes a high level of neglect for a long time for this stuff to emerge,” he said “It’s like black mold: It will grow if nobody is cleaning it up.”

Christina K. Daly, DJJ secretary, said “allegations of honey buns or other rewards used as discipline or for attacking youth have been fully investigated and found to be unsubstantiated.”

Daly, in an interview with the Herald, said instigating detainee violence is “not a practice, a systemic practice of this agency. It is not acceptable to me, and any time the allegation is raised, it is our responsibility to investigate that.”

As to records of abuse by staff examined by the Herald, she said: “Unfortunately, these things have happened and all we can do is move forward and do what we can do to prevent them from happening in the future. ... All we can do is work with our staff, train our staff and be very clear what our expectation is.”

‘You’d do a lot for a Snickers’

Twenty years back, a Miami juvenile court judge held hearings about abuses in a now-shuttered Pahokee youth facility. One boy testified he was conscripted to fight in matches staffers organized for their “excitement.” He said he was paid in candy bars.

Marie Osborne, who has overseen the Miami-Dade Public Defender’s Office’s juvenile division for decades, questioned witnesses and remembers the boy explaining: “You’d do a lot for a Snickers.”

More recently, a Miami Gardens teen told the Herald an officer put a “honey bun on [his] head” after the two argued over an unapproved trip to the restroom. “I went to the bathroom. I didn’t ask no permission,” said the youth, who asked not to be identified. “He came to me [and said] the next time you do that, I’m gonna show you something.” The teen replied: “That’s a threat?”

The teen acknowledged cursing at the officer, and taunting him: “You ain’t gonna touch me.”

And he didn’t touch the youth. The youth’s friend told him “that man put a honey bun on your head.” Later, two detainees jumped him, injuring his neck, he said. “When I got back to the mod, mod four, the two kids who jumped me had honey buns,” he said.

The teen’s father said he viewed video of the attack at the detention center and what he saw shocked him. “They did not stop the fight.”

“The other kid said, ‘you have to be ready, because an officer put a honey bun on your head. At any time, another kid can jump you,” the father said. “They are using the other kids to fight. Enjoying the fight. Watching the fight. It’s not right.”

His son, who was 15 at the time, spent six days in the hospital, records show.

This youth says he was beaten up by two fellow detainees at the Miami lockup after exchanging harsh words with an officer. Afterward, the attackers were eating honey buns available only from the staff vending machines. A friend told him: "You know that man put a honey bun on your head." The youth's face is obscured to protect his identity. -Emily Michot

Allegations of “hits” and “bounties” and other acts of officially sanctioned mayhem have persisted year in and year out. A sampler:

▪ In 2008, a detainee at the Milton Girls Juvenile Residential Facility in the Panhandle told the state’s child abuse hotline that a staffer ordered other workers to stand down while detainees attacked her. “Let them fight,” the worker said — and her colleagues did. The girl told investigators her life was in danger. The allegation was substantiated.

▪ In 2009, DJJ confirmed allegations that, on Easter Sunday, the program director of Camp E-Kel-Etu in the Ocala National Forest loaded a small boy suspected in the theft of hygiene supplies into a truck, and drove him to an off-campus service road. The director of the program, since closed, brought an older boy with him to terrorize the kid into spilling what he knew, an internal report said.

When the director returned to the campsite, he rounded up four other “little boys” — the youngest was 11 — and stuck them in a supply room with two older youths, said an internal DJJ report. The gear room housed canoe paddles that he hinted could be used as weapons. He “picked up a paddle and threatened to allow” the bigger youths to “beat up the younger and smaller boys,” one of the younger detainees told investigators. Rather than get whacked with a paddle, one of the boys talked.

▪ In 2010, two detainees at the St. Johns Youth Academy claimed a staffer had ordered them to jump another teen, saying “someone needs to fight him.”

The worker opened the victim’s door, and let the attackers in, the two intruders told investigators. One punched the 17-year-old in the face, leaving a gash; the other choked him so violently he suffered three fractured neck vertebrae.

The program operator concluded “staff intentionally unlocked the door” so the youth could be beaten. The worker was fired. But a DJJ investigation called “inconclusive” the allegation that the officer set up the attack, saying it was his word against that of the two boys.

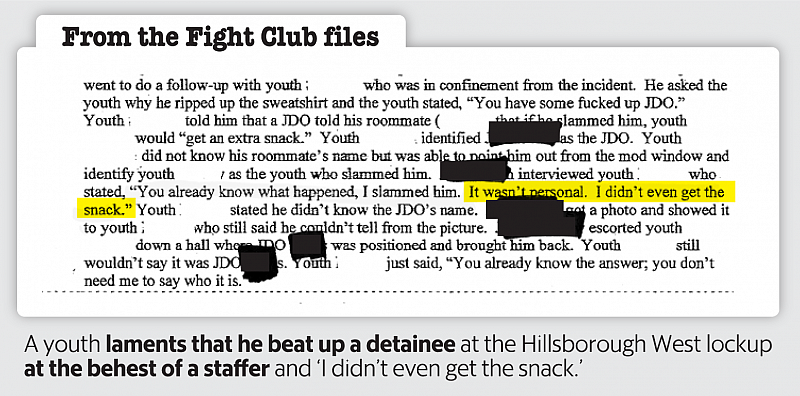

▪ In 2011, a 16-year-old at the Hillsborough West Detention Center told an investigator he “slammed” his roommate after a worker promised him an extra snack. The 15-year-old victim said his roommate picked him up — twice — and threw him down on the floor both times. The victim hurt his right ankle.

When an assistant superintendent interviewed the attacker, he admitted everything. “You already know what happened,” he said. “I slammed him. It wasn’t personal. I didn’t even get the snack.”

DJJ reported that the staffer failed “to conduct himself in a professional manner.” He was fired.

When fights aren’t investigated

It’s difficult to determine, on a case-by-case basis, what triggers the violence in Florida’s lockups and youth programs. Records suggest that juvenile justice administrators do not investigate the lion’s share of detainee beatings. If officers and workers are to blame for some or much of it, no one is gathering the evidence.

In 2015, when 17-year-old Elord Revolte was beaten to death by a mob at the Miami detention center — a beating that two detainees said was instigated by an officer — DJJ reported 53 fights among youths at the lockup, 36 of which resulted in an arrest for battery, prosecutor and DJJ reports said. Aside from Elord’s beating, only one of the fights resulted in an internal DJJ investigation, said a 2016 inspector general report.

During the investigation into Elord’s death, one detainee told an inspector that he had “witnessed staff place snacks on youth’s heads and request youth be beaten up by other youth.”

Over the past five years, police and DJJ have fielded complaints about staff-arranged fights in at least eight institutions in six areas, including Fort Lauderdale, Miami, Jacksonville, Tampa, West Palm Beach and Okeechobee. As recently as last February, a 14-year-old boy accused a Broward lockup officer of telling him to hit another detainee.

An incident at the Duval Academy on July 16, 2014, shows what can happen when teens are deputized to enforce rules. Workers in Jacksonville called their program “Positive Peer.” It left a 15-year-old positively traumatized.

Boys at the Jacksonville academy were picking on a smaller kid. They shoved his shirt inside their pants, and then threw it into a garbage can, he said. A staffer stood and watched. When the youth refused to wear the shirt, workers postponed breakfast for everyone.

A DJJ administrative review describes what happened next: A supervisor “entered the day room and appeared to make a gesture with her hands. Immediately following the gesture, several youths ... began to physically force a shirt over the head and upper body of the youth.” That supervisor and a colleague watched from a few feet away without interfering as the boy was swarmed.

When the teen removed the shirt again, the two staffers attacked him, he told investigators. Detainees consistently said one worker wrapped her fingers around the youth’s neck and choked him, leaving visible bruises. The kid “was crying, and the other youths were laughing at him,” the DJJ report said.