Lockup officers groomed him to beat up other teens, mom says. It cost him his life.

This article and others in this series were produced as part of a project for the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism’s National Fellowship, in conjunction with the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

Powerful lawmaker calls for juvenile justice review in wake of Herald series

At this juvenile justice program, staffers set up fights — and then bet on them

Dark secrets of Florida juvenile justice: ‘honey-bun hits,’ illicit sex, cover-ups

FIGHTCLUB: A Miami Herald investigation into Florida’s juvenile justice system

Annie Steeter, grandmother of Maurice Harris Jr., and her daughter, Shakila Stewart, share photos and a program from Maurice’s funeral service. On the table beside them is a memorial to Maurice’s father, Maurice Harris Sr., who was slain during a home invasion robbery. Emily Michot

By Audra D.S. Burch and Carol Marbin Miller

An aspiring basketball player standing six-foot-three, Maurice Harris Jr. fit the profile for one of the non-advertised jobs at the Miami-Dade juvenile lockup: enforcer.

The pay was cheap, his mother said: $2 sticky buns, hamburgers and, for the most difficult tasks, a new pair of sneakers. But the job description was simple. Maurice need only use that imposing frame to punish other detainees who had provoked the wrath of officers.

Nobody told Maurice about the risks — one of which found him on a street corner a year after his release.

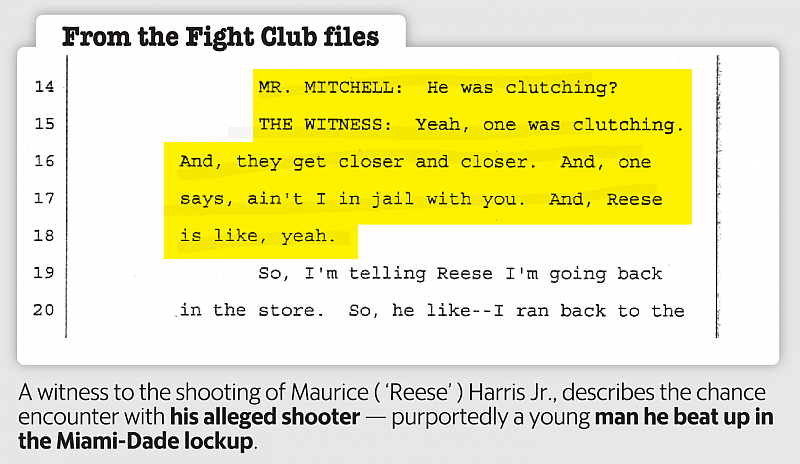

“Ain’t I in jail with you?” asked 19-year-old Everton Demetrius Ramsay, as he ran into Maurice near a Liberty City store on Labor Day 2015. Ramsay, police say, then pulled a handgun out of his waistband and shot Maurice eight times, execution-style, leaving him to die on the pavement.

Maurice’s story, ending in the Resurrection section at Caballero Rivero Dade North cemetery, next to his father, Maurice Sr., echoes accusations throughout Florida’s juvenile justice system of staff paying bounties — contraband fast food, candy bars and especially honey buns — to detainees willing to beat up other youths. And it is an example of how mayhem inside the system can spill out into the streets.

Maurice was 16 years old, and big for his age, when he entered the Miami-Dade Regional Juvenile Detention Center on May 23, 2014. He had been arrested for car theft and trespassing, but added a new charge, battery, five days later.

Maurice shared his secret with his mother during Wednesday afternoon calls, she said: He was doling out discipline as a hired gladiator.

“I gotta do what I gotta do,” he told Shakila Stewart.

What he had to do, he said, was “survive in here.” But he was a fighter full of remorse. “He told me he didn’t want to fight the boys because he hated bullies,” Stewart said.

In one egregious incident recounted to police, Maurice kicked a smaller youth in the face. That youth was the 5-foot-11, 145-pound Ramsay, according to one of Ramsay’s friends, who later described the encounter to police. Ramsay spent 21 days at the lockup, from May 31 through June 20, 2014.

When the two crossed paths a year later in Liberty City, the payback was deadly, police say. Ramsay denied the shooting to police, and has yet to face trial. His attorney, Gregory Gonzalez, declined to discuss the case.

Maurice was killed just days after the death of another youth suggested the existence of a mercenary culture in the Miami lockup. Shortly after 17-year-old Elord Revolte was punched and stomped by a swarm of detainees on Aug. 30, 2015 — he died the next day — the Miami Herald reported that the youth may have been “honey-bunned,” or attacked in exchange for a gooey treat.

After that story was published, Stewart contacted the Herald and said her son had been killed for his role as an enforcer at the lockup.

Everton Demetrius Ramsay

The Department of Juvenile Justice looked into Stewart’s claims after the Herald quoted her saying lockup officers rewarded her son with honey buns, Snickers bars, ice cream and McDonald’s burgers for doing their bidding. A Jan. 11, 2016, DJJ inspector general report expressed skepticism, noting that Stewart never reported her concerns in real time to anyone at the agency. She told an investigator “she did not believe [Maurice] at that time.”

In the course of that investigation, as well as probes by police and prosecutors, youths collectively described a near-primal culture of teenagers coerced into service as goons-for-hire. They recounted how the most intimidating detainees were recruited for the dirty work.

In those statements, as well as interviews with the Herald, youths talked about cellblock beatdowns for punishment and matches staged for entertainment. They described a dark but simplistic way to survive: Beat or be beaten.

The stories were credible enough that a 2017 Miami-Dade State Attorney’s Office memo, which closed out an investigation into Elord Revolte’s death, concluded it was “likely” that staff had engaged in the practice of recruiting enforcers.

“Instead of being rehabilitated, they had him in there fighting,” said Stewart, 38. “If he wasn’t fighting, none of this would have happened. My baby would be alive today.”

His father’s murder

Annie Streeter, 58, a grandmother of nine, including Maurice, is petite and direct with a booming voice that fills the living room. She sits on the sofa and sighs deeply. Maurice, she said in an interview, never really recovered from a childhood horror: his father’s murder.

Maurice Renard Harris Sr. was shot in a home invasion robbery in 2013 as he tried to protect his sleeping 11-year-old daughter — Maurice’s younger sister — from the killers, police said. Behind the anonymity of bandanas, they shot Harris, 36, repeatedly in front of Stewart, his wife of six years. His son, Maurice Jr., wasn’t home.

Six days later, as the limousine carried Maurice Harris Jr. up Northwest 27th Avenue to his father’s final resting place, the 15-year-old turned to his mother and promised that he would become the man of the house.

That march toward manhood was marked by bad luck and bad decisions. Maurice, his mother said, stumbled through his freshman year in high school. He retreated into silence, then into the streets. He was facing trespassing and car theft charges when he was booked into the Miami-Dade Regional Juvenile Detention Center in May 2014 for one of two stays that year.

The 126-bed lockup is a worn, squat compound, with its own ugly history. It was supposed to be the first stop on Maurice Jr.’s path to starting over. The sign inside the foyer makes a promise: Treat each child as if they were your own.

A detective who investigated Maurice Jr.’s killing described him this way: “Big-ass guy.” He entered the system after a growth spurt, an ideal candidate for imposing his will on others. Weeks into his stay, Maurice called his mother to tell her he had broken another boy’s jaw in a fight on the orders of staff, Stewart said. That was the first fight, but not the last.

Stewart said her son described one of his assignments: “He was inside the cafeteria. The guard told him, ‘That one over there.’ He got the tray and hit a guy upside his head, and he was rewarded for it,” Stewart said. “His reward was the honey bun, or the sneakers, or even they would go to McDonald’s and get him whatever he wanted.”

After four months, Maurice was transferred to a program in Central Florida. He spoke to his mother by phone almost every Wednesday afternoon. Upon completion of the program, he planned to get his driver’s license and enroll in the 11th grade at Northwestern High, becoming a third-generation Bull.

“He said he had done a lot of bad things while he was in DJJ and was ashamed of his behavior,” his mother said.

Maurice returned home to Liberty City, Streeter said. He was looking for a brighter future. He completed probation in August 2015, and had stayed out of trouble since his arrest the year before. “He was very excited about school, very excited. He was ready to play basketball,” she said. “A light came on and he could see he was going down the wrong path.”

Maurice left home Sept. 7, 2015, Labor Day morning, to walk to the Pork ’N Beans — slang for the Liberty Square public housing complex — to see his best friend, Stewart told police. She made Maurice a plate of ribs, collard greens, and macaroni and cheese and put the food in the fridge for when he returned home.

Surveillance video obtained by the Miami Police Department showed some of the teen’s final moments: He was walking east on a sidewalk around the 1300 block of Northwest 54th Street when a handful of young men began to follow. Seconds later, the video captured some of the boys running west on 54th.

A friend of Maurice’s, identified in police and court records only as E.H., told detectives he had met Maurice at Charles Hadley Park on 50th Street, and the two were walking back from a store when they passed the other young men. One of them had “red skin,” and was wearing a white T-shirt and a black “skully,” a brimless hat, said E.H., then 14.

The male in the skully eyed Maurice.

Friends of both boys told police that the young man in the skully asked Maurice if they had known each other in the lockup. Ramsay, the youth in the skully, then reached for his waistband “as if he was grabbing a firearm,” E.H. said.

“I ran back to the store,” E.H. said in a sworn statement. “As soon as I ran in the store, I heard the [shots].”

D.M. was one of the young men walking with Ramsay — who was also known as “Nunu.” It took 145 minutes of verbal parrying for a homicide detective to convince D.M. to describe what happened that evening:

D.M. told police he “immediately recognized” Maurice as the boy who had kicked Ramsay in the face during a fight in the Miami lockup. D.M. told police “he [D.M.] pulled up his pants and was ready to fight,” but Nunu shot Maurice first.

An autopsy showed Maurice had been hit eight times — including twice in the chest, once in the right thigh and once in the left hand. Four of the slugs struck Maurice in his buttocks, suggesting his killer was determined he not get away. Two shots missed their target.

Back home, Stewart was holding her infant daughter, Emerald, at 6:30 or 7 p.m. when Maurice’s friend PeeWee appeared in the doorway, delivering the news.

Stewart staggered outside, nearly tripping over the bike PeeWee had flung to the ground.

Streeter came outside and, in her calmest voice, declared the news untrue. “Just go. Just go see what happened.”

Maurice was still breathing.

Stewart got in her car and willed herself the four miles to Ryder Trauma Center, where a team of doctors worked to repair the catastrophic damage. They couldn’t.

Ramsay’s revenge, Stewart said, was almost inevitable: “ ‘When I get out, I’m going to handle it my way’ — and that’s what he did.”

Every other week, Stewart visits her husband — and now her son — at a cemetery off Opa-locka Boulevard. Many who died violent, premature deaths ended up in this vast memorial field, including gunshot victims Trayvon Martin and Sherdavia Jenkins.

The father and son, killed two and a half years apart, were interred together in a plot without a headstone. An etched stone marker bearing both names is planned. The earth is topped with two of everything: flower vases, RIP hearts and stuffed puppy-dog toys, along with wind chimes and a fabric sign that reads, simply, “LOVE.”

“I like to sit on the ground because it feels like I am closer to them,” says Stewart, brushing away the leaves.

The young man accused of gunning down her son, Ramsay, is charged with second-degree murder and carrying a concealed firearm. His Facebook page was decorated with various photos of himself and others flashing firearms, sometimes pointing directly at the camera. He told police he was walking to the store when he heard the gunshots that killed Maurice — but didn’t fire them.

Maurice, who had promised to become the man of the house on the slow ride to the cemetery during his father’s funeral procession, nearly made it.

He was buried on his 18th birthday.

[This story was originally published by the Miami Herald.]