Long Beach's Leap Towards Livability, Part IV: Leaping Forward?

In 2008, the city of Long Beach, Calif. was awarded a Policies for Livable and Active Communities and Environment (PLACE) Grant. In this series, Damien Newton examines the strides the city has made toward transforming itself into a more livable community.

Long Beach's Leap Towards Livability, Part III

Long Beach's Leap Towards Livability, Part IV: Leaping Forward?

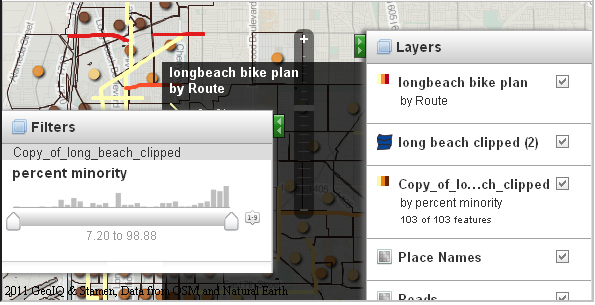

The above map, which can be viewed in full at http://geocommons.com/maps/96184#, shows Long Beach broken down geographically by census data and racial diversity. The lighter the dot, the higher the percentage of residents are Caucasian.

During the past three years, Long Beach has shown a commitment to pushing the envelope when it comes to promoting clean and green transportation options. However, the purpose of this article and last week’s series is to examine if the city has lived up to its agreement with the L.A. County Public Health Department to fulfill its Policies for Livable and Active Communities and Environment (PLACE) Grant the city was awarded in 2008.

The other four communities that received a PLACE Grant used their funds to bring in experts and planners to create master plans. Long Beach used most of their grant to hire Charlie Gandy, a leader in the field of transportaion infrastructure and a spokesman that oozes charisma, but by his own admission “isn’t much of a master plan guy.”

As a result, the other four communities provided me with hundreds of pages of documents prepared as part of their grant. Long Beach provided quite a bit less, although what they did provide is part of a Master Plan update that is planned for later this year. But for now, Long Beach is in first place among the five cities that received PLACE Grants, but they’re in fifth as far as the planning portion of the grant.

That’s the bad news. The good news is it appears that based on the information available, Long Beach is on the right track. In the long-run, the content of the final document is what’s most important, not what month it is passed in.

While Long Beach city staff have worked on updating their mobility element, much of the city’s attention has been drawn to the innovative measures bicycle projects and that’s by design.

“We wanted to show people what was possible,” explains Derek Bunham from the city’s planning department. ”It can be hard for the public, hard for the decision makers, to see the policy on a large scale. So we decided to show them what can be done with demonstration projects.”

Many of these pilot projects have been in business districts and the well-to-do community along Vista Street, where the first Bike Boulevard was put in earlier this year. Four different people commented to me, all on background, that Long Beach was “putting in the most for the people that need it least” with its progressive programming.

Longtime Long Beach resident Alan Allesio was not one of those people. Alessio refers to the much-praised infrastructure as “kind of a tease” to the rest of the city and “There are certain areas that got a lot, and if you happen to live in that area, then you can really dig what’s going on. I don’t live in one of those areas.”

For their part, city staff understands their issues and says that better bike projects are on their way for the entire city soon. “When you build demand, you start with the early adopters, the neighborhoods that get it and want to go first,” Gandy explains. ”We were funded for fifteen miles of bike boulevards, and we’ve just begun with 1.5 miles. The rest will happen, and they won’t happen on streets that look like this one.”

In other words, the city is hearing complaints about equity but when the funded projects are completed, the projects that will most likely get done barring something unforeseen happening, then the equity issue will vanish. Rather than just take city staff at their word, we created this map to test their claims.

You can view the full map at GeoCommons.

The above map breaks Long Beach up in to its different census tracts. Inside each tract is a small circle which shows what percent of the residents living inside the tract are minorities and how many are Caucasian. Clicking on the dot will give you that data. The red, orange and white lines show bike projects that will be completed in the short-term. Clicking on the line will tell you what street, the length of the project, and whether the project will be a bike lane, bike boulevard, or something else.

The map demonstrates that the city, if it follows through on the short-term and funded projects in the map, that the city will create a network that serves communities of all races and will provide residential connections to the beaches, the Downtown, the new transit plaza and those Bike Business Districts that are proving so popular.

But that’s not to say that existing bicycle infrastructure, even the new ones in the upper-class, mostly Caucasian neighborhoods or business districts are for everyone.

“There’s our indicator species,” Gandy remarked during our bike tour, gesturing to a Latina woman and two tween-age children on beach cruisers heading down Broadway on a trip to the beach. ”She feels comfortable enough in a separated bike lane to ride in normal clothes, without a helmet. That trip is probably made in a car without that lane.” Don’t worry, the kids were wearing bike helmets.

Later on our ride, we followed a family of five, all Latino, and their neighbor from next door, who was riding to the beach path from Pacific Avenue across town. When we chatted with the family. In the words of the father, “No way we would have tried this a couple of years ago. No way.”

Or, as former Long Beach resident and founder of the L.A. County Bike Coaliton Joe Linton put it, “Long Beach is the most bike friendly city in Southern California. All that new infrastructure is used by everyone, regardless of where they live.”

But while Long Beach has tripled its infrastructure of bicyclists in the last three years, the city has also been working on an update to the circulation element to its Master Plan. As Bunham put it, “the policy is going to catch up the infrastructure.”

The city has done outreach to create an element that incorporates both traditional and new facilities for cyclists and pedestrians. While the plan hasn’t been revealed to the public, a twenty-page document entitled “Principles for Active Living and Complete Streets” that outlines the goals that Long Beach’s transportation and circulation element should meet when it comes to the City Council in the fall or early winter.

“If you look at our existing Mobility Element, you see a lot about road widenings about moving cars,” Dunham explains, “Now we want to focus more on people than cars. Focus on pedestrian, bike ant transit travel This is such a big shift, we wanted to create a public document that showed the principles so that people can see what we’re talking about.”

“We’re not trying to play a zero sum game, or declare war on the car or anything like that. We’re trying to link modes together not get rid of one.”

So what does “Principles for Active Living and Complete Streets” promise Long Beach? It outlines the principles that Long Beach should follow.

— Balance the Needs of all Modes of Travel

— Promote Walking

— Promote Bicycling

— Promote Transit

— Create Dynamic and Context Sensitive Streets

— Protect and Enhance the Environment

— Build Healthy and Active Neighbors

— Create Transit Oriented Development Along Transit Routes

— Ensure Connectivity to Active Routes and Other Modes

“Our big focus has been on shifting short trips,” explains Ira Brown, who is working on the Master Plan update with the planning department. “People would usually take the car to go to the laundromat, go to the store, and that trip can be made on a bike or by foot. We want to help people make that decision.”

Which isn’t to say that there’s nothing for advocates to do in Long Beach. While the principles and maps released are a great start, there are always things that can go wrong in a couple of months. When Long Beach does release its Draft Master Plan this fall, Streetsblog will update its Long Beach series.