The long reach of childhood trauma — Part 1

Research has linked exposure to abuse, neglect and other forms of severe adversity in childhood to a wide range of mental and physical diseases and disorders. Can understanding this make a profound change in the way we prevent illness? This is the first article in a four-part series.

Arielle Levin Becker wrote this story while participating in the National Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of USC’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. Her project is archived here.

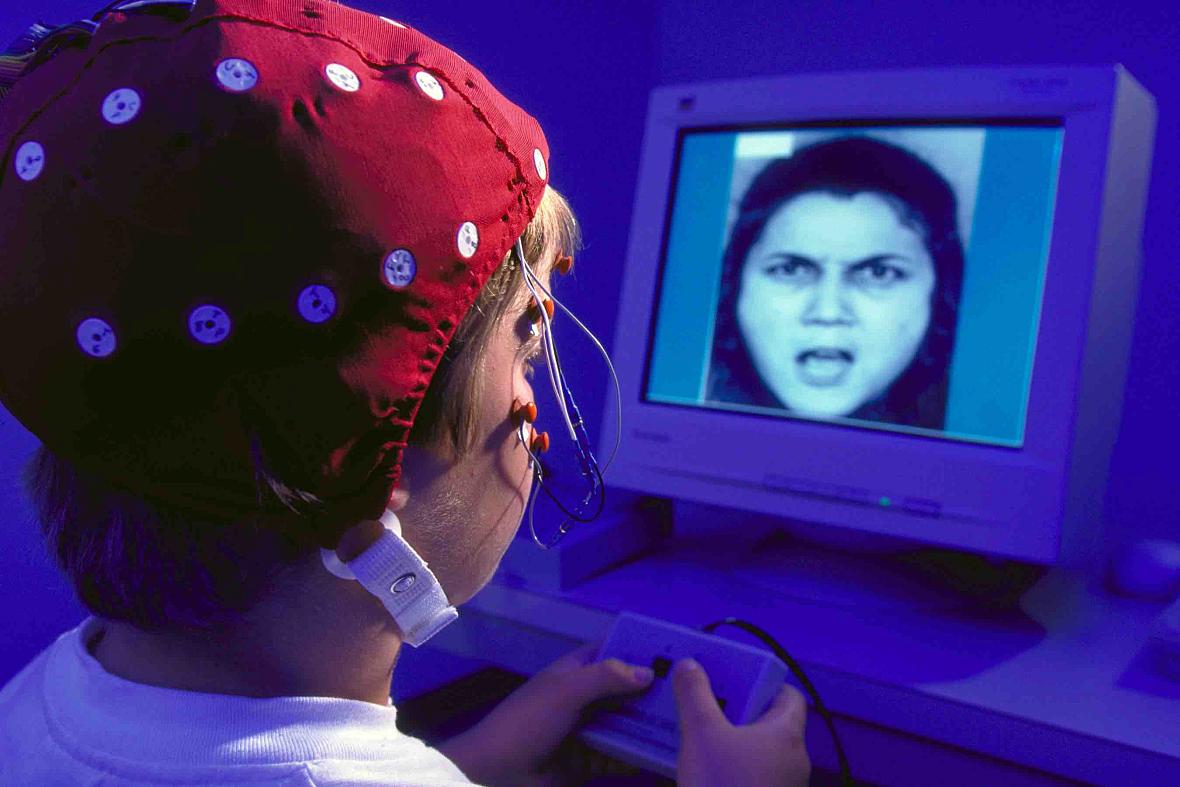

Researchers measured children’s brain activity while viewing facial expressions. Children who were abused were more likely to view ambiguous faces as angry. (Courtesy of the Child Emotion Lab at the University of Wisconsin - Madison)

The woman had dropped out of the weight-loss study. So had a frustratingly high number of other patients, most of whom seemed to be succeeding at losing weight before quitting. This confused Vincent J. Felitti, the doctor leading the 1980s study.

So he began interviewing the dropouts, using a series of questions designed to create a timeline of their lives and weight history. The woman's answer to one of them would help set Felitti on a far different course, inspiring decades of work he'd never anticipated.

How much did you weigh when you became sexually active? Felitti asked.

“She said, ‘40 pounds,’ started crying and blurted out, ‘It was with my father,’” he recalled.

In his career as a physician and head of the department of preventive medicine at Kaiser Permanente in California, Felitti had rarely come across a patient with a history of incest. But by the end of 186 interviews, 55 percent of the obesity patients had reported being sexually abused. Worried he’d somehow biased the responses, Felitti asked five other people to interview another 100 patients. Their results were the same.

He was puzzled. Could this be possible?

Felitti’s curiosity would eventually lead to a landmark study that found childhood abuse, household dysfunction and other forms of early life adversity were common – and linked to a greater risk for both mental health problems and physical illnesses, including heart disease and cancer.

It’s hardly surprising that abuse and other hardships in childhood can carry substantial consequences. But increasingly, researchers have been trying to understand why. Can early adversity cause disease, and if so, how? Why do some children seem to escape unscathed while others struggle? And can answering those questions point the way to interventions?

Based on a growing body of evidence, researchers now say that young children’s exposure to severe adversity – like abuse, neglect or violence – represent not just tough circumstances but experiences with the potential to carry lasting mental and physical consequences, potentially influencing development of parts of the brain involved in learning and memory, and the way the body responds to stress.

It’s not deterministic. Many people withstand serious adversity without significant consequences, and many who experience trauma recover. Scientists say there are genetic differences in how susceptible children are to the effects of their environments and other factors that contribute to resilience, including the presence of a supportive caregiver who can help buffer the effects of stress. And researchers say that while the brain is most malleable when children are young, it maintains its ability to change through life.

But Felitti and others say the findings point to an opportunity still not widely reflected in health care policy or medical practice. It’s a view shared by some of those now leading social service and public health programs in Connecticut:

A key way to target adult diseases, reduce health care costs and address a host of problems throughout life is to start early, focusing not on symptoms of illness but childhood adversity and the factors that can protect against its effects. That includes identifying and treating trauma early, to stem deeper problems from developing.

“It’s a real epidemic,” said Alice Forrester, executive director of the Clifford Beers Clinic in New Haven. “Adversity, toxic stress, trauma, all of these are really high-cost, high-impact risk factors that drive every human service cost out of control.”

After his early interviews with the weight-loss study dropouts, Felitti was met with skepticism. An attendee at a 1990 conference told him the reports of abuse were excuses “for failed lives.” Then someone from the Centers for Disease Control suggested he see if the findings could be validated in a general population.

The result was the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study, a survey of more than 17,000 Kaiser Permanente patients – a middle class, privately insured group.

Participants answered questions about their health and whether they had experienced one of seven types of adversity in childhood: sexual, emotional and physical abuse; domestic violence; or living in a household with someone who abused drugs or alcohol, had mental illness or went to prison. (The researchers later added physical and emotional neglect, and having divorced or separated parents.) Each person was assigned an “ACE score,” based on the number of different categories they experienced.

Just under two-thirds of the participants reported at least one type of adverse experience, and 12.5 percent reported experiencing four or more. One in five said they had been sexually abused. Twenty-eight percent reported being physically abused.

And as a person’s “ACE score” rose, so did the person’s likelihood of abusing drugs or alcohol, being severely obese and having depression or a history of attempting suicide. So did the person’s likelihood of having illnesses including cancer, chronic bronchitis, hepatitis and heart disease. The risks were particularly strong for those with four or more ACEs.

Some of the connection is the result of behaviors like smoking, alcoholism and drug use, all of which were more common among people with higher ACE scores. But even after controlling for those sorts of risk factors, researchers found that people with higher ACE scores had a higher likelihood of having conditions including liver,heart and lung disease.

There are limitations to this kind of research. Someone with serious medical or mental health problems might spend more time dwelling on potential early life causes and report them when surveyed.

But other studies, including research that followed children into adulthood, have reported similar findings.

One found that children with four or more ACEs were 17 times more likely to have learning or behavior problems than those with no ACEs, and nearly 50 percent more likely to be overweight or obese. Other studies have found problems linked to children's exposure to neighborhood violence.

"In the context of everyday medical practice, we came to recognize that the earliest years of infancy and childhood are not lost but, like a child's footprints in wet cement, are often life-long," wrote Felitti and Robert Anda, an epidemiologist and ACE Study co-author.

Felitti wasn't the first to examine links between stressful experiences and other problems. By the the time Seth Pollak began his career more than two decades ago, research had linked child abuse to a host of bad outcomes.

But Pollak, a psychology professor at the University of Wisconsin, wondered why. How come the way you’re treated at age 2 would influence the way you play with other children at age 5, your school performance at 10, your risk for substance abuse at 14, or the way you parent your own children? And why would it be related to developing diabetes and heart disease in your 60s?

“How’s it getting under the skin? Why is it affecting so many different parts of an individual’s life, and why is it cascading over such a long period of development?” Pollak wondered.

He started by looking into things others had taken for granted.

“People kept saying that abused kids tend to be very aggressive, they tend to be quick to anger, they tantrum a lot,” he said. Were there corresponding differences in brain physiology?

He designed an experiment in which children looked at pictures of people expressing emotions, while he recorded brain physiology to monitor their attention and memory systems.

It turned out the abused children had high levels of brain activation when they saw angry faces, but not other facial expressions.

Subsequent studies found similar things: Preschoolers who had been abused by their parents were more attuned to anger when overhearing strangers arguing. Children who had been abused were more likely than non-abused peers to interpret an ambiguous face as angry. Children who were neglected had trouble distinguishing emotions.

To Pollak, the findings suggested that the children’s brains were adaptive. The children were being hurt by the people who were supposed to protect and nurture them. They had few defenses. But their brains could specialize in detecting a potential threat, learning the cues that signaled an adult’s mood had changed.

The problem is, those adaptations come at a cost.

If you see anger in an ambiguous face, what happens when a teacher approaches you with a neutral expression? Or if you’re on the playground and misread another kid?

“If you respond as if you’re about to be attacked, which makes sense to you, you are going to be labeled as an aggressive child,” Pollak said.

There’s another problem too: The more you see threats in your environment, the more your brain is likely to set in motion a physiological stress response.

And, researchers believe, stress is one of the key links between early adversity and disease.

And, when the systems are functioning normally, they turn off when the threat is gone.

But if the stress-response systems are activated frequently, or for prolonged periods, it can take a toll on the body, producing what researchers call “wear and tear” – and vulnerability to disease.

Frequent or prolonged activation of the stress-response systems in young children, in the absence of a supportive adult who can help them cope, can have particularly severe consequences, researchers say. A group of researchers based at Harvard's Center on the Developing Child dubbed this "toxic stress," and warn that it has the potential to affect parts of the brain involved in learning, memory and perceiving threats, and to set children's stress-response systems to become overly reactive or under-responsive to threats.

Research indicates that early experiences, starting prenatally, calibrate the stress-response system, said W. Thomas Boyce, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine, who co-authored one of the first journal articles on toxic stress.

“The newborn is unconsciously sampling the environment to determine, ‘Just what kind of a world have I been born into?'” Boyce said. “And what is going to maximize my survival and fitness in this world?”

When a child has too many experiences with danger or unpredictable threats, “It’s almost like their brain decides, ‘Well, this is a dangerous world, I’m going to stay on alert,’” said Patricia Wilcox, who leads the Traumatic Stress Institute at Klingberg Family Centers in New Britain. “And they get stuck in that danger activation mode.”

It's hard to learn when you're living in a heightened state of anxiety, focused on danger, she noted.

“When something actually happens in the present,” she said, “instead of just going from a base level to some more activation, they’re going from a high activation to a super-high activation, and they may seem to others to be over-reacting.”

How does stress lead to disease? Remember, the stress response affects immune functions, which are needed to fight disease. One of those functions is inflammation, which, in chronic form, has been linked to illnesses including heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

If a person’s physiology has trouble regulating the stress response – something found to occur in some adults who were abused as children – could it also have trouble regulating inflammation?

One team of researchers found that, compared to people who hadn't been, adults who were maltreated as children were 60 percent more likely to have elevated indicators of inflammation in their 30s, after controlling for other risk factors.

“Childhood maltreatment is a preventable and potentially treatable childhood risk factor for poor adult health,” they wrote.

Other researchers have examined links between early adversity and cancer, theorizing that exposure to stress could weaken the immune system’s ability to detect tumor cells. In one study, scientists found that skin cancer developed faster in mice that had been subjected to chronic stress – spending hours a day in restraints – than in mice who hadn’t, in part because of a weaker immune response.

There are also indications that early experiences can interact with a person's genetic code and influence whether certain genes get expressed or not.

There’s evidence, for example, that a mother rat’s licking and grooming of her baby in the first week of life helps produce a better-regulated stress-response system by influencing the expression of genes involved in the system. Studies have suggested a similar process could occur in humans, including one examining the brains of suicide victims that found differences in gene expression between those who had been abused as children and those who hadn’t.

Researchers are also looking into genetic differences that could help explain why some children are more heavily influenced by their environment – whether good or bad. Scientists are examining whether, for example, having a particular variation of a gene could make a person more susceptible to depression after experiencing maltreatment.

But there’s a long way to go in understanding the full picture, said Jay Belsky, a professor at the University of California, Davis.

“It’s almost like we’re getting ever more appreciative of how complex the puzzle is,” Belsky said. “We’re getting a sense of what part of the board certain puzzle pieces are going to go in” – but it’s not yet clear how they fit together.

The ACE Study isn't new. Its first findings were published in 1998.

“If that study was about broccoli, it would be all over the front page of The New York Times,” Wilcox said. “The trouble is it’s just such a huge thing to change.”

“We have this incredible proof about the expense that trauma is causing our society and how all of these physical ailments are related,” she said. “And yet, what do you do to change it? It’s not like, ‘Well, eat more broccoli.’”

After the study, Felitti’s department at Kaiser Permanente added questions about adverse experiences to the questionnaire patients fill out before their physical exams. When doctors see the results, they can ask, “Can you tell me how that’s affected you later in life?”

Felitti said it’s paid off. A study found patients who were asked the trauma-oriented questions had 35 percent fewer doctor office visits and 11 percent fewer emergency room visits the following year.

He thinks it’s because asking the questions serves a purpose akin to confession in the Catholic Church: a person tells something shameful about himself to a person of authority, “and in the course of a couple of minutes, comes away understanding that they still are an acceptable human being.”

“The impact of that is extraordinary,” Felitti said. “And yet, it’s gone nowhere.”

Even the other departments at Kaiser Permanente, where the ACE Study was conducted, haven’t started asking patients about adverse experiences, Felitti said.

So he’s concluded that the best approach lies outside the doctor’s office, in something he imagines could be modeled in the plotline of a television show.

“If you were to ask me what my thoughts are on the most effective public health advance that I can think of in current times, I would say to figure out how to improve parenting skills across the nation,” he said. “There is that huge portion of the population that has had no experience with supportive parenting themselves, many of whom might do better if they only knew what it looked like.”

This article was originally published by The Connecticut Mirror.