Medical harm

A number of studies have shown that between 3 percent and 33 percent of patients suffer some type of medical harm while hospitalized. In Oregon, with annual hospital discharges topping 340,000 patients, that means more than 100,000 people could be harmed while being cared for in hospitals across the state. In this project, Betsy Cliff reports on the patient safety issues in Oregon health care systems.

Part 1: Medical harm

Part 2: Oregon releases less health data

Each year thousands of patients are harmed by medical care in Oregon.

A Bend woman, Mary Parker, was one.

Parker, who filed a medical negligence lawsuit in Deschutes County Circuit Court, went into St. Charles Bend in June 2010 for the removal of her thyroid gland. She had growths on her thyroid, the lawsuit describes.

During the surgery, the lawsuit alleges, Dr. Gary Frei, a surgeon with Bend Memorial Clinic, sliced a nerve that controls one side of her vocal cords. That caused paralysis of a cord, Parker alleges, resulting in pain and difficulty speaking, swallowing liquids, and breathing.

Parker sued Frei last summer, asking for nearly $1 million in damages. The case is scheduled for trial in May.

Patient safety is a major concern at nearly every hospital across the country, and yet experts say hospitals are still not safe enough. While every hospital interviewed for this series — nearly 20 institutions, including most of the state's largest hospitals — cited a focus on patient safety, studies show patient harm remains common.

“As well as we're doing,” said Jodi Joyce, vice president for quality at Legacy Health in Portland, “health care is not as safe anywhere as we would like it to be.”

An analysis done for The Bulletin by the Office for Oregon Health Policy and Research found that in 2010, patients experienced more than 4,000 potentially preventable complications in Oregon hospitals. That's just over 1 percent of the total number of discharges that year. The analysis includes issues such as foreign objects left in the body after surgery, postoperative bloodstream infections, breathing failure after surgery, postoperative hemorrhages, trauma to a mother or baby during delivery, collapsed lungs due to medical treatment, and accidental lacerations during surgery — the allegation of the suit against Frei. While some of these complications are more likely to cause major harm, the amount of injury to the patient can vary with any of them.

Hospital executives argue that these data include errors in patient records that may not be true complications. But studies indicate that this analysis may understate the true incidence of patient safety problems.

A number of studies have shown that between 3 percent and 33 percent of patients suffer some type of medical harm while hospitalized. In Oregon, with annual hospital discharges topping 340,000 patients, that means more than 100,000 people could be harmed while being cared for in hospitals across the state.

In 1999, a report from the Institute of Medicine found that each year up to 98,000 people in the United States die due to problems caused by hospital issues that could have been prevented. That's more than the number of people who died in 2010 from motor vehicle accidents, AIDS and homicide combined.

Hospitals can be “dangerous,” said Anna Jaffe, director of quality at Ashland Community Hospital. “You don't want to scare people. ... But you also want them to understand that they can be.”

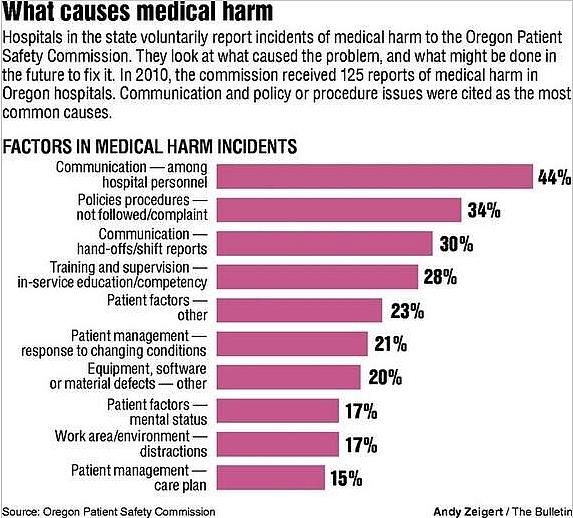

Patient safety issues can come in a number of forms. Some are caused by mistakes, either human errors, gaps in communication or simply misinformation about a patient. Other events are harder to pinpoint. Some surgical complications — for example, serious blood clots or surgical infections — have proven methods for reducing their incidence, but are not typically caused by outright mistakes.

The financial costs are tremendous. A 2010 study sponsored by the Society of Actuaries put the total cost of treating medical injury at $17 billion a year in the United States. That's to say nothing of the pain and suffering it can cause to patients and their families.

The cases of several Oregon patients illustrate how devastating it can be when the very care meant to heal, harms instead.

Complications

The complication during Parker's surgery shows how fine the line can be between a mistake and a complication. Frei, in court documents answering the initial complaint, admitted damage to the nerve. In the documents, he maintains that nerve injury can be a complication of the procedure, and was discussed with Parker prior to surgery.

Indeed, nerve damage is commonly cited as a complication of the surgery by major medical organizations, including the National Institutes of Health and the Mayo Clinic.

Parker, reached by phone last month, said she had no comment. Her attorney did not return calls for comment.

Frei declined to comment, citing the pending litigation, said a spokeswoman for BMC. His attorney, as well, declined comment.

The clinic, through a spokeswoman, sent an emailed statement from its chief medical officer, Dr. Sean Rogers. It said, in part, “despite taking all reasonable precautions, every medical procedure involves some risk of harm to the patient.”

The trial in Parker's case will likely hinge on the extent to which the incident represents a mistake versus a clinical complication.

Some complications are preventable, said Dr. Knute Buehler, an orthopedic surgeon and board member at St. Charles Health System who was not involved in Parker's case. “But the thing about complications is there are usually lots of different things that go into causing them.”

Leslie Ray, a patient safety consultant for the Oregon Patient Safety Commission, gave the example of one event reported to her. At one Oregon hospital in 2010, a patient was recovering from knee surgery when she suddenly stopped breathing. The hospital called a code, indicating that the patient was in an immediately life-threatening situation.

As they were trying to resuscitate the woman, the hospital staff realized they didn't have the bag mask ventilation unit, which forces air into a patient's lungs, on the emergency cart. Without it, patients in this condition are deprived of oxygen. Someone ran to get another bag to use, but that one was broken.

Finally, the third bag worked, Ray said. The woman was successfully resuscitated but, perhaps owing to the lack of oxygen to her brain, was not as alert as she had been before the incident. Staff at the hospital, said Ray, “were concerned that even that short period of time, running to get the third one, was too long.”

Her mental decline reversed a few weeks after being in the hospital, according to the report to the Patient Safety Commission. But the hospital found systemic issues that could have caused another, perhaps even more serious, incident. “They didn't have a clear procedure for the time and the frequency of checking the emergency supplies,” Ray said. The hospital has since implemented a way to do so, she said.

Slow progress

Across the country, progress in patient safety has been slow.

“There have been modest improvements in patient safety each year,” said Helen Burstin, a senior vice president for performance measures with the National Quality Forum, a nonprofit organization focused on hospital performance standards.

But Burstin and others said there is a considerable way to go. Improvements, she said, are not “to the scale that everyone would have hoped.”

A part of the problem is the complexity of providing health care. Each patient sees many physicians, nurses and other staff members during the course of a hospital stay.

Sometimes, even the most well-meaning interaction can cause serious harm, as illustrated by the case of Paxiownut “Floyd” Shock, who died at St. Charles Bend on May 31, 2008.

Shock, a member of the Yakama Nation, had been in a car accident that left him paralyzed. He was in the hospital nearly a month, but was set to be released soon when a staff error caused him to suffocate. The hospital announced his death several days after it occurred, and local news outlets, including The Bulletin, covered the story.

But at that time all the details, including the exact circumstances of his death, were not known. A state report from the Department of Health and Human Services (now the Oregon Health Authority), obtained by The Bulletin through a public records request, shows how easy it can be for an innocent interaction to turn into serious harm.

According to the report, a certified nursing assistant who had cared for Shock on May 30, 2008, stopped by his room the next day “to say, ‘Hi.' ” Shock was using a tracheostomy tube to help him breathe, as is often the case with quadriplegic patients.

Shock's tracheostomy tube had been fitted with a special type of removable valve to help him speak. The valve worked in such a way that if it was on, a cuff on the tube needed to be deflated to allow air to pass out, allowing the patient to breathe.

The CNA put the valve on Shock's tracheostomy tube because of difficulty understanding Shock, according to the report. It's unclear if she knew how to use the valve. The state report says the hospital reported it was “completely out of (the CNA's) scope of responsibilities” to put the valve on the tracheostomy tube.

Shock said he was in pain, according to the state report, and the CNA left the room to report that complaint to a nurse. As she left, Shock's valve was left attached and the cuff was inflated. That meant Shock could take air into his lungs but could not exhale. It was a grave mistake.

Thirty minutes after the CNA left, another CNA came into the room to test Shock's blood sugar. He was unresponsive. That CNA called a nurse, who called an emergency code.

Several hospital staff and a physician responded, and initially got Shock's heart to begin beating. But Shock remained unresponsive. According to the state report, the physician stopped resuscitation efforts after reviewing a form stating Shock's own wishes for how much medical intervention he wanted in case of this type of life-threatening situation, and after consulting with a second physician.

Shock died about an hour after the nurse called the code.

The hospital revised some of its practices, including transitioning to tracheostomy tubes that did not need cuffs, according to a spokeswoman for the hospital just after the incident. The hospital also placed an employee on leave, the spokeswoman said.

The state report revealed that the issue may have been more systemic than it first appears. For example, managers and executives interviewed by the state said CNAs were not authorized to have contact with the type of valve attached to Shock's tracheostomy tube. But that restriction was not in writing, the state found, nor could the managers say how staffers were made aware of that restriction.

Similarly, the valve comes packaged with a warning sign stating the danger of inflating the tracheostomy cuff with the valve in place. That sign, which is supposed to be posted in a “highly visible” location such as above a patient's bed, according to the state report, was found “under other papers lying on the bedside table next to (Shock).”

Most cases of medical harm involve multiple systems or processes in a hospital, said Ray at the Oregon Patient Safety Commission. When a patient is injured by medical care, she said, “you can see one or two people that were the agent that delivered the harm, but when you look at how it happened, there are usually multiple people involved or multiple systems.”

She investigates many of the events that lead to medical harm in Oregon hospitals. In the past few years, she said, “I doubt that we had any events that had less than three contributing factors.”

Shock's family settled a wrongful death suit for $400,000 with the hospital later in 2008, according to court records.

The effect on at least some family members, however, remains.

Yolanda Smith, Shock's daughter-in-law, said last month the experience made her more wary of medical care. She and her family, she said, stopped by the hospital the night before Shock died, and were some of the last members of his family to see him alive.

His death made her feel “like I shouldn't trust (hospitals),” she said. “I wouldn't want something like that to happen to me.”

What you can do for yourself

There are things that patients can do to help protect themselves from medical harm. Most experts say it comes down to being an advocate for your own care or bringing someone who can advocate for you.

“Our encouragement is for them to speak out,” said Pam Steinke, vice president for quality and chief nursing executive at St. Charles Health System, which runs three hospitals in Central Oregon.

That’s not always as easy as it sounds. Other hospitals have found that patients tend to be shy. “Our patients tell us that they don’t always feel safe bringing up concerns (about safety to staff) because it may suggest larger questions about trust or confidence,” said Jodi Joyce, vice president for quality and patient safety at Legacy Health in Portland.

But most experts said it is important, even if uncomfortable. Here are some tips that address how to speak up and other things you can do to stay safe while hospitalized.

• Ask questions. Medical care is “a whole lot safer if you really engage,” said Helen Burstin at the National Quality Forum, a nonprofit organization focused on hospital quality. Don’t be afraid to have medical staff repeat information you don’t understand.

• Ask physicians, nurses or anyone who touches you if they have washed their hands. Hand washing is perhaps the easiest way to prevent the spread of infection at hospitals. Staff are typically instructed to do so both entering and leaving a patient room, though surveys have found it’s often missed.

• If a patient is a smoker, it’s recommended they quit smoking a few weeks before elective surgery, said Dr. Patrick Romano, a professor of medicine at the University of California, Davis, and an expert on patient safety. The complication rate for nonsmokers, even those who quit for just a few weeks prior to surgery, is substantially lower, Romano said.

• Leave the hospital. “The longer you stay, the greater your risk of acquiring an infection,” said Romano. That means you should try to plan for some recovery at home.

• Make sure doctors know about every medicine you are taking, including vitamins and herbal supplements. If you can’t remember them all, bag them and bring them to an appointment.

• When you are being discharged, ask the doctor to explain the treatment plan you should follow at home. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, a federal agency focused on quality improvement, says this means learning about new medications, making sure you know whether to schedule follow-up appointments and finding out when you can go back to your regular routine.

• If you are having surgery, make sure you, your primary care doctor and your surgeon all agree on what is going to be done. Patients at St. Charles can expect that the surgical site is marked before the patient is put under anesthesia.

• If you have a choice of hospital, look up hospital quality scores. Try hospitalcompare.hhs.gov for a number of quality measures and search infection rates through the state’s Office of Health Policy & Research (www.oregon.gov/OHA/OHPR).

* Ask the surgeon how often he or she performs the procedure and how often it is done at the hospital. Research has shown the more often a procedure is performed, the greater the likelihood of good results.

• Have a family member stay with you and talk with physicians as much as possible. It’s not always easy to be an advocate for yourself when you’re compromised by illness or recovering from surgery.