Medical records supporting San Francisco's universal care add millions to official cost

Could San Francisco have figured out a model for providing universal health care on a tight budget?

The California Endowment Health Journalism Fellowships at USC Annenberg sponsored a reporting project by Michael Stoll, along with a team of reporters at the San Francisco Public Press, to take a closer look at whether local health care reform ideas are working in one major metropolis. More than 40 individuals also donated to this project via Spot.Us. Reporting, photography and research for this project were contributed by Barbara Grady, Angela Hart, Kyung Jin Lee, Cindy Chew, Jason Winshell, Monica Jensen, Tom Guffey, Siri Markula and Frank Bass.

Part 1: Some employers drop private health plans for San Francisco's subsidized public option

Part 2: Participants appreciate safety-net health access program, but note gaps

Part 3: Medical records supporting San Francisco's universal care add millions to official cost

The San Francisco Department of Public Health says it is ahead of the curve in rolling out databases that keep tabs on tens of thousands of patients across a citywide network of clinics and hospitals. The rollout is needed not just to make a local form of “universal health care” work, but also to meet a 2014 deadline under national health reform.

And the city says it spent just $3.4 million on new patient-tracking technology. Not bad for an unprecedented charity care initiative whose total budget has grown to $177 million just this past year.

But while clinics and hospitals across the city are now linked up to a common intake tool that eliminates overbilling and duplicated medical appointments, that is only the first step in making the Healthy San Francisco program successful, directors of local health centers and technology experts say.

A separate and much more complex piece of technology — electronic health records — is proving difficult and expensive. Knitting together incompatible computer systems across the 35 medical sites so they can easily share detailed patient medical records could costs the city millions beyond what is included in the official price tag.

An incomplete survey of technology costs borne by the clinics themselves this year reveals spending of at least $15 million in addition to what was budgeted for the whole program, adding at least 8.5 percent to the total cost. But that sum is likely millions higher, since eight clinics could not or would not say how much they spent or were planning to spend integrating their patient records.

The Department of Public Health claims that Healthy San Francisco costs just $276 per patient per year — a real bargain compared with the average for private insurance — at $402. But building something that looks like insurance on top of an established public-private safety net can mask the technology requirements and other hidden costs of reform.

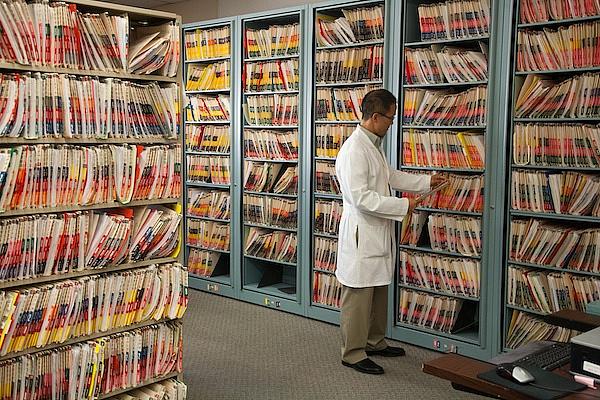

The current patchwork of at least 11 different computer systems across the network do not easily talk with one another. As of the fall of 2011, at least 23 clinics were stuck in the 20th century, relying on large storerooms of paper records not easily shared with specialists or emergency room doctors.

This incompatibility of recordkeeping sometimes causes delays, repeated tests, unnecessary procedures and gaps in care as patients move from doctor to doctor. Ideally, say technology planners, there ought to be just one system citywide. But that is unlikely to happen soon.

The 16 health centers in the network that are operated by the health department, plus San Francisco General Hospital, will get the most comprehensive database upgrades. The process started last January and will continue through the end of 2013. The system, called eClinicalWorks, will cost $11.1 million for software, computers, office equipment, training and extra staff to manage all the data, and roughly $5 million a year thereafter to maintain.

But among the 17 other clinics, private health providers and hospitals currently developing their own transition to electronic health records, many are fundraising on their own to stay ahead of the curve.

Medical directors from the Sunset to the Mission to Chinatown have reported steep costs for upgrading technology, purchasing equipment and staffing the rollout of these systems.

“It’s rather urgent that things start moving toward electronic-based medical recordkeeping,” said Jonathan Howell, the information systems manager for the Community Clinic Consortium, which includes about half of the safety-net clinics citywide. “It could save untold millions, and huge amounts of staff time.”

Money is not the only impediment. Some medical staff are reluctant to change entrenched work habits. And many clinics have already invested in obsolete systems and are waiting until they need to upgrade.

They can’t wait too long. Health care providers across the country are facing a 2014 federal health care reform deadline for moving patient records online.

Experts say electronic records, a key to President Obama’s Affordable Care Act, could reduce medical errors by improving the accuracy and clarity of medical information. The initiative promises to give doctors the ability to improve care, cut costs and target preventive care to specific populations such as diabetics or AIDS patients.

Cutting-edge software and infrastructure is expensive. The 14 nonprofit clinics in the Community Care Consortium network are struggling and competing for federal funding to catch up.

One already financially stressed clinic, Lyon-Martin Health Services in Hayes Valley, which caters to the gay, lesbian and transgender communities, said buying a new electronic records system might break the bank.

Prevention needs information

One of the first things Healthy San Francisco accomplished in 2007 was to deploy a citywide patient enrollment system, One-e-App. For the first time, patients knew they would not have to sit through interviews to re-enroll in each clinic. Also for the first time, the city knew how many people were using the system, when and where.

Healthy San Francisco’s director, Tangerine Brigham, said before deploying One-e-App, the enrollment system was “confusing” and resulted in wasted time for staff and people seeking care.

“It has been invaluable for us,” she said. “It has allowed us to have one system of records for our population in terms of their enrollment, their disenrollment, demographics, and our hospitals now have access to find out who is eligible for other charity care programs.”

But One-e-App contains no medical data. And in fall 2011, at least 23 clinics still relied on paper records. When doctors want to refer a patient to a specialist elsewhere, their charts must be scanned, faxed, mailed or retyped. Eliminating this clerical work could save the network millions of dollars each year and reduce chances for error.

Brigham said the city is far ahead of others in the ramp-up to nationally mandated health reform.

The medical records system the city chose, eClinicalWorks, was deployed at the first city-run clinic in August. It also is coming to San Francisco General and will allow some online records-sharing. Still, there are speed bumps. While the clinics can see General’s medical files, they cannot currently add to them.

While Brigham said improving electronic health records is not strictly necessary for cheaper, coordinated and more efficient care, she acknowledged that improved recordkeeping could help Healthy San Francisco achieve those goals.

A medical error can add up to millions of dollars in extra expenses, both for the city and the sick.

One patient living on $100 a month was sent to the emergency room because of a cardiac arrest, said J.P. Perino, administrative manager at Glide Health Services in the Tenderloin. The patient was charged $2,200 for the ambulance ride, plus the cost of the expensive emergency room visit. She didn’t know precisely how much the emergency room visit cost, but according to standard rates treating a heart attack can cost between $13,000 and $18,000. Perino said the debt went to collection, until the clinic redirected the bill back to the city.

“This was a Healthy San Francisco patient,” she said. “These costs weren’t billed correctly, largely as a result of the inability to share patient records.”

Electronic information sharing is not the only way to make Healthy San Francisco more efficient. The program also gives each patient a “medical home” — one clinic or hospital that is the first place for patients to go with a health problem.

Brigham said the medical homes model creates a stable enrollment base. More than 73 percent of participants in Healthy San Francisco are continuously enrolled, “which is pretty good for an uninsured population who didn’t before have that kind of access to care.”

That shifts the burden from emergency to preventive care, which is far less expensive. Providers can call a patient when she is due for a mammogram or a flu shot, for example. It also reduces unnecessary cost by allowing providers to track a patient’s health over time.

Brigham said medical homes dramatically reduce the per-patient cost of care. But the total burden on the General Fund has increased because there are more patients using the services.

Nonprofit clinics scrape by

Some non-city run clinics still operate with old-fashioned paper medical charts kept in gargantuan filing cabinets or rooms of shelves filled with rainbow-colored tabs. Clinics across the country are now competing for limited federal grant money to purchase new electronic health record platforms. Many are taking on much of the startup costs themselves by scraping together money from other federal and state funding and from philanthropy.

“These systems are incredibly expensive,” Howell said. “You could pay up to $10,000 for up-front costs, but then there’s ongoing costs — the initial software purchase, training and licensing and technological refreshes. Those costs can easily outpace the purchase price.”

He compared it to a cell phone: “You buy your fancy new phone, for say $700, and that sounds expensive, but then you look at the ongoing bills: $100 a month, $120 a month. It adds up.”

As a result, San Francisco clinics are operating on a variety of technology systems, most of which don’t talk to each other. That causes problems when a patient moves from one medical home to the other. The end result is more expensive care.

“Interoperability is a big problem in terms of setting the same standards system-wide, while keeping patient confidentiality through encryption,” said Stephen Shortell, dean of the School of Public Health at the University California-Berkeley. “But these are big challenges that are mounting nationally — they’re not unique to Healthy San Francisco.”

According to the school’s research, last year 18 percent of Medicare patients nationwide were re-admitted to the hospital because of miscommunication, wasting $12 billion.

“These are tools that are supposed to improve patient care and coordination and reduce repeat procedures,” he said. “This shows us the cost for preventable re-hospitalization — meaning if they were properly treated on an outpatient basis, they wouldn’t have been readmitted.”

Duplicated procedures

Doctors at some clinics have significant problems in taking on new patients because they cannot easily absorb electronic files patients bring from other medical centers.

On a recent day outside the Lyon-Martin offices on Market Street and Octavia Boulevard, Dawn Harbatkin, the center’s medical director, described a persistent problem: “Often, I’ll send a patient to a specialty clinic, and I’ll have important lab results and imaging that was done elsewhere but the specialist doesn’t have access to any of that care because they can’t retrieve it from our system. What happens is repeat tests and duplication of expensive procedures, because they can’t get ahold of our information.”

In interviews with the Public Press, a dozen clinic medical directors underscored the same problem. They agreed that the advent of medical homes makes care cheaper in the long term. But as clinics adopt incompatible records systems, appointments can get duplicated and some services can go unbilled because staff cannot figure out the proper medical codes.

“We, as a city, are far from being able to share data between clinics,” said Albert Yu, the medical director at Chinatown Public Health Center. “That’s a problem, because say I have a patient, and they were transferred to California Pacific Medical Center for chest pain, but their medical home is here. Those providers don’t track contextual elements in terms of this patient’s past. Patient history, medications, lab data, diagnostic workup data, allergies, and that’s not even mentioning if they don’t speak English.”

The resulting miscommunication could lead to unnecessary or even harmful treatments or tests, if the patient has, for example, an unrecorded allergy to a medicine.

“There are real problems,” Perino said. “Duplicated procedures, extra labs ordered or X-rays possibly. And because people can’t exchange information quickly, the insult is to the taxpayer.”

Centers fund own upgrades

Kenneth Tai is the medical director for North East Medical Services, one of eight nonprofit medical homes in the city. His clinic, also in Chinatown, sees about 50,000 patients annually, 60 percent of whom are uninsured.

Anticipating the federal move toward electronic health records, Tai got together in 2007 with Mission Neighborhood Health Center and South of Market Health Center to apply for a grant to build one computer system for all three.

The $2.5 million system, called NextGen, was fired up at North East Medical Services two years ago. The Mission clinic planned to roll it out by December, followed by South of Market in 2012.

Tai said the most useful part of the new system is the ability to audit the patient population to improve services to those needing similar care.

“Instead of before, pulling 100 charts at random to get patient data, now we can just check a box and it generates a list of, say, all of my patients with high blood pressure, or patients with diabetes, or women who are due for a pap smear,” Tai said. “It allows us to reach out to more patients and be more proactive in targeting care.”

However the process hasn’t been easy. Tai has seen training problems with the shift from paper to digital. Patient privacy is more easily compromised by hackers or human error.

Howell said keeping records secure when sharing information is something a citywide information technology committee is currently grappling with.

“We take this very seriously,” he said. “But there are vulnerabilities.”

Tai couldn’t estimate how much the clinic had paid beyond the $2.5 million grant, but he did know that it was “a lot.” The clinic needed at least 300 new computers, to implement NextGen, adding hundreds of thousands of dollars in cost.

Ricardo Alvarez, the medical director at Mission Neighborhood Health Center, said his clinic needs 30 new computers which, coupled with staff training and other software, could cost an additional $500,000. The clinic sees about 13,000 patients annually, only about one-quarter of whom are Healthy San Francisco enrollees.

Across the network, that means the cost of upgrading all the clinics could run in the millions.

“This is going to be fundamental for medical homes in the future,” Alvarez said.

Still using fax

Ocean Park Health Center, a health department-run clinic, launched eClinicalWorks in August. The clinic is small — just six medical personnel and 3,400 patients. It used to be smaller, but uninsured patients there have tripled since Healthy San Francisco began. The clinic needed a laundry list of additional equipment, which it paid for itself, said medical director Lisa Golden.

Golden said she purchased six computers, five printers, two webcams, two keyboards and a fax machine. A half-dozen people were hired for testing, training and troubleshooting. Doctors, nurses, assistants and technicians who worked part time were bumped up to 40-hour workweeks.

When all health department clinics are finally up and using the system, providers will be able to look at records simultaneously. But Golden is already seeing efficiencies emerge: a reduction in simple handwriting mistakes and more coordinated care.

Before digital records, she said, “medication refills would come in as a fax. That required pulling of paper charts and sorting through information, then reviewing the prescription and faxing it back. But now refills are electronically transmitted. They come in and get sent back immediately.”

And yet in other ways, Golden said the move away from paper charts has actually slowed productivity. Before eClinicalWorks, a patient visit averaged about an hour of work for clinic staff. Now it is 15 to 30 minutes longer because the workflow of medical staff has not caught up with the technology.

“It takes time to transfer information from the paper record into the electronic format,” Golden said. “We’re reviewing charts longer and deciding what to scan and what to type in as a summary. And it’s also just understanding where to click. It’s not second nature yet.”