Mental health court growing, 'changing lives'

The National Alliance on Mental Illness estimates that approximately one in five state jail prisoners have "a recent history" of a mental health condition. Jail health care officials say that it's one in four in Tulare County.

This story is the fourth in a series about mental health care in Tulare County. It was produced as a project for the The California Endowment Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of USC's Annenberg School of Journalism.

The high cost of childhood trauma

Too many patients, too little housing in rural California county

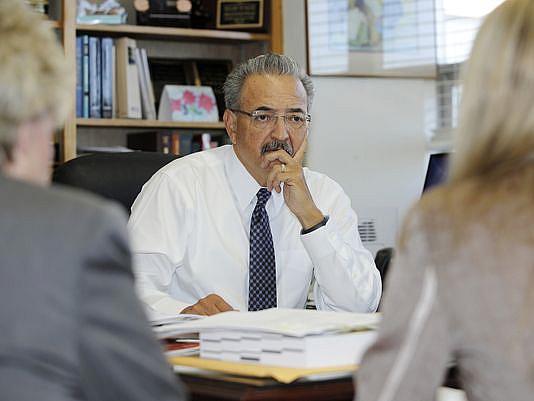

Photo: Juan Villa

Brandee, a 44-year-old married mother of four living in Visalia, didn't want to be one of a growing number of inmates being treated for some form of mental illness.

The National Alliance on Mental Illness estimates that approximately one in five state jail prisoners have "a recent history" of a mental health condition. Jail health care officials say that it's one in four in Tulare County.

Facing several drug charges that could've placed her behind bars, she requested referral to mental health court — a small, specialized county court geared toward defendants with severe mental disorders — that offered an alternative form of rehabilitation that officials say is far more effective than jail. And it's cheaper too.

"When I heard there was a mental health court, I ran for it," said Brandee, who asked that her surname be withheld due to the nature of her illness. "It's given me my life back."

Why is it needed?

Retired Judge Glade Roper was among those who helped bring the mental health court to life in 2009. Roper and other law enforcement officials saw a problem, specifically among people with mental illness.

"When I first became a judge, the justice system just wanted to throw everyone in jail," he said. "Well it turned out that didn't work."

Mental health care clients — many of whom self-medicate with illegal drugs — were riding an unending merry-go-round. Jail did little to rehabilitate them and often aggravated their conditions and was incredibly costly to the taxpayer. But there was no alternative, Roper said.

"For years, I would refer people to the mental health department, but you've got to be clean and sober for 90 days to start treatment. So addicts couldn't do anything about their illness until they didn't have a drug problem," Roper said. "But the addiction programs wouldn't help them with their addiction until they'd been treated for their mental illness. What's a judge to do? Putting them in cages doesn't help."

The solution was to design a program that gave mentally ill defendants with minor offenses — violent or sexual crimes are automatic disqualifiers — an opportunity to get help outside of jail.

While similar programs were beginning around the country, they were few and far between.

"We're a cutting edge county," said Deputy Public Defender Cheryl Smith, who works extensively with the program.

"This was something Tulare County did because it was the right thing to do — everybody just anteed up," said Christie Myer, the chief probation officer for the county.

How it works

Mental health court is a much different environment than criminal court. The program is the fruit of collaboration among officials in the district attorney's office, the public defender's office, county probation and the county mental health department.

Officials sort defendants and forward offenders with low-level crimes to the district attorney's office, which decides whether a person is eligible based on predetermined criteria.

Once the district attorney determines that a person is eligible, mental health officials perform their own evaluation to determine whether the defendant has a qualifying mental disorder (usually bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or severe depression with psychotic features.)

When Brandee entered the program, she received a diagnosis, medication and therapy to treat her bipolar disorder, post traumatic stress disorder and depression. She now makes frequent visits to court, where probation officials and mental health officials update the judge about her progress.

The hearings are frequent and the programs demands high. Defendants must plead guilty to the charges against them but if they can complete the entire program, their charges will be dropped.

Many of the defendants are simultaneously linked to addiction services or supportive housing — whatever it takes to get them stabilized.

Why it works

It all starts with medication. But many with mental disorders are afraid of medication — and not without reason. Strong drugs often include strong side effects. County mental health officials say it can take a long time to figure out the right medication and the right dosage for a particular patient. But it's a vital process.

"The baseline is that they must take their medications," Judge Valeriano Saucedo said. "We help them understand that meds are lifelong."

Once the person has accepted medication, there's a rigorous schedule of court hearings, probation meetings, drug tests, support group meetings and therapy sessions. Good attendance is required to stay in the program.

Saucedo meets with officials from each department every Thursday morning to hear updates on each case. He then uses a package of rewards and sanctions to keep participants on the right path. Each success earns a public pat on the back and each failure brings a loss of freedom.

This week, Saucedo was impressed with Brandee's progress.

"The notes are very positive," Saucedo said Thursday in court. "It says you've stepped up your program."

Smiling, Saucedo asked Brandee about her children and then led the courtroom in a round of applause.

"There's usually some tension in court or some fear," Brandee's attorney Clark Hiddleston said. "Judge Saucedo has made it more positive, therapeutic and encouraging."

Besides the medication, Hiddleston believes the frequent hearings with the judge are a big reason people stay on track.

"There's no substitute for being face to face with a judge every week," Hiddleston said. "It's a very effective means of keeping people on the right path."

Smith agreed, citing the importance of the positive reinforcement that her clients can earn every week.

"We're very proactive in acknowledging success," she said. "For many people they've never heard that before... Think about what that means when a judge comes off the bench, shakes their hand and presents them with a certificate. The judge's position is to inspire."

Higher highs and lower lows

Because officials are investing so much more time and energy in each case, mental health court feels like a roller coaster. The highs are higher and the lows are lower than regular cases.

"I'm more emotional in mental health court," Hiddleston said. "There's dramatic successes and dramatic failures ... It's very rewarding, but it can be heartbreaking, too."

The hardest part for Brandee — and for many participants — is coming to terms with their mental illness. Those who fail to take their medication risk failing out of the program entirely. So far, Brandee has accepted them. They've given her a new outlook on life.

"I'm getting tools to find out who I am besides being a mental patient," she said.

Cost and savings

Not every story in mental health court has a happy ending, but officials in several departments say they happen more often than not. And rehabilitating mental health clients without jail saves the government thousands of dollars in the long run, they say.

The operating costs of the program are difficult to measure. Each department has a couple of positions committed entirely to mental health court, but there are plenty of other ancillary personnel who play a role as well. Personnel costs for the probation department are about $163,000 per year. The mental health department's personnel costs are about $290,000 per year.

Attempts to secure similar data from the district attorney's office and the public defender's office before the publication deadline were unsuccessful.

The mental health care treatments have a cost, but there are many other sources of funding for treatment, so that's not factored into the cost of the court.

The savings — to some extent — are easier to quantify.

In fiscal year 2012-13, mental health court clients avoided 13,210 days in jail by participating in the program. With jails costs estimated at $70 per day, the program saved just shy of $925,000. There are also other savings associated with fewer arrests and simpler court proceedings that are difficult to estimate.

None of the components are funded with grants, which officials say are often short term. Instead, each department has attempted to use existing resources to fund the court. The long term savings, they say, justifies the funds taken from their general budgets.

And the court has expanded in the past five years. To accommodate that growth, the program was split into phases, with participants earning graduated levels of freedom as they move throughout the program. Not having to see every client every week has freed case managers to take on more cases.

Saucedo says that with the way the rules governing the offenses and disorders that qualify for the program are written, the court's supply of manpower is able to meet the current demand. Wait lists do exist, however, for housing and other supportive services within the program. Because of this, many mental health court clients must wait in jail for a bed in a mental health facility.

"It's very hard to tell someone in jail to just wait a little longer," Smith said. "Those I feel bad for."

Recidivism

In Hiddleston's experience, about two out of three of his mental health clients finish the program. Since 2009, the program has accepted 176 clients. Probation records indicate that 63 people have finished the program, 68 did not finish (for a variety of reasons) and 45 are still moving through the system.

Of the 63 who have finished, six have been convicted of another offense within three years — amounting to a recidivism rate of 9.5 percent.

By comparison, the recidivism rate for Tulare County convicts who've been released under prison realignment tied to AB 109 is 28.4 percent.

"I would say [mental health court clients] are doing remarkably well," chief county probation Officer Myer said. "It's a very labor intensive process, but it's paying off."

This story is the fourth installment of a series on mental health care in Tulare County. It was produced as a project for the California Endowment Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of USC's Annenberg School of Journalism.

Mental illness in jail

The National Alliance on Mental Illness estimates that one in five inmates in state and local jails nationwide have a recent history of a mental health condition.

In Tulare County, jail health officials report that about one in four inmates are treated for mental illnesses.

Recidivism

9.5 percent — The recidivism rate for mental health court graduates

28.4 percent — The recidivism rate for prisoners released early as a part of prison realignment mandated in AB 109.

Savings

$924,000 — The amount of money saved in fiscal year 2012-13 just from keeping mental health participants out of jail. Costs of running mental health court cancel some of these savings, but officials say low rates of recidivism among graduates amounts to savings in the long term.

Photo Credit: Juan Villa

This article was originally published by the Visalia Times-Delta.