Mobile dental clinic brings care to poor children in Prince George's County

Named after a 12-year-old boy who died from complications resulting from an infected tooth, the Deamonte Driver Dental Project provides care to children who do not have dental insurance coverage. The three-chair mobile clinic strives to prevent additional deaths caused by untreated tooth decay.

At last, dentist Belinda Carver-Taylor was sitting in the new mobile dental clinic with a child before her. She had hoped for this day so long that now she could only shake her head.

"This is my dream!"

Nearly four years after bacteria from an infected tooth spread to the brain of 12-year-old Deamonte Driver and killed him, the dental clinic named in his memory had made its first stop - at his old school, the Foundation School in Largo. Its mission: to prevent another child from dying from untreated tooth decay.

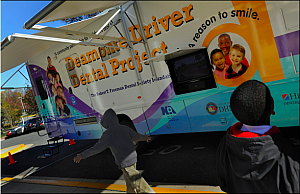

The three-chair mobile clinic where Carver-Taylor and other volunteer dentists were welcoming young patients was a little bigger than a school bus and painted in happy tropical colors. On this sunny November morning, the white awning outside opened like a sail. When the vehicle's steps came down, Betty Thomas, the manager of the Deamonte Driver Dental Project, leaned out the door and smiled. "Are you ready?"

And four little boys stepped in, huddled shyly.

Soon, the place was swirling with kids playing with the toothbrush puppet; getting their teeth examined, cleaned and swabbed by the dentists and assistants; and having their treatment plans charted on clipboards.

Outside, Dina James, director of Foundation, a private nonprofit school for children with emotional disabilities, studied the mobile clinic and recalled Deamonte.

"I wish there was a picture of his smile up there. He had the most gorgeous smile I have ever seen," she said. "He was our baby."

Soon after the boy's death, she had gotten a call from a dentist, Hazel Harper, who lived nearby and had a practice in Washington.

"She said, 'I feel so bad about being one of the dentists in the area,' " recounted James. " 'I want to come and talk to you. To see that this doesn't happen again.' "

Now, after endless work and hours of meetings, among school nurses and health officials and volunteer dentists and hygienists and dental assistants, the mobile clinic was real. It was here.

Yet the job of bringing adequate dental care to the poor children of Prince George's County would not be a simple one. State and national public-health officials have been grappling with the same challenges: to educate both poor people and dentists; to address the historic breach between oral health care and the rest of health care; to confront the vast gaps in the dental public-health system.

"We know that this is new territory," said Harper. But, she added, "we don't want to see another child die."

Shocking news

Dental caries, also known as cavities or tooth decay, is a communicable disease. It starts with common bacteria, often passed from mother to child. The bacteria form acids in the mouth, demineralizing tooth enamel. Decay is preventable with good oral health practices. Without them, it can progress, penetrating the tooth's hard surfaces, allowing bacteria to infect the tooth's interior and causing an abscess. Without attention, the infection can travel to surrounding tissue or other organs, including the brain.

On Feb. 25, 2007, Deamonte Driver died after two brain surgeries and six weeks of hospitalization that cost more than $250,000. Deamonte hadn't complained about his teeth. When he got sick, his mother, Alyce Driver, had been searching for a dentist for his brother. But it was hard to find dentists in Prince George's County who were participating in Medicaid, the joint state and federal health-insurance program for the poor.

News of Deamonte's death cast a light on the shortcomings of the Medicaid system, which is mandated to provide dental care to 30 million poor children nationwide. But fewer than a third of Maryland's 500,000 Medicaid children had seen a dentist the year before, a rate that was typical of states across the country.

The Driver family's poverty, periods of homelessness and difficulties with transportation, phone service and mail delivery all complicated the search for care.

Still, it came as shocking news that a child should die in a wealthy state such as Maryland for lack of an $80 tooth extraction - for lack of the basic preventive care routinely available to privately insured children.

Harry Goodman, a former state dental director who was brought back to replace an acting director after Deamonte's death, said it could have been prevented "if he had sealants, somebody providing some level of education, if he had some level of prevention . . . and also someone at some point going into the schools and looking and saying, 'Wow, Deamonte, you got this big hole in the back. I'm going to send a note home, I'm going to send one to the nurse and set up a system of care where you guys don't fall through the cracks.' "

A succession of congressional hearings probed the problems, with a large picture of Deamonte's face displayed on video monitors around the hearing room.

"With all the resources available to us, how did we so thoroughly fail this little boy?" asked Rep. Elijah E. Cummings (D-Md.).

The hearings revealed a system in disarray. A review of the records of UnitedHealthcare, the managed-care organization that shared responsibility for Deamonte's care at the time of his death, concluded that thousands of Maryland Medicaid children had not seen a dentist in years. The review, faulting both UnitedHealthcare and the system, also found that families confronted major barriers to finding participating dentists. Cummings's subcommittee concluded that an inadequate number of dental providers was a problem nationwide. Reforms were demanded.

"Deamonte took us by the hand . . . and escorted us through the health-care system and pointed out all the places where we could improve," Rep. John Sarbanes (D-Md.) said this month at a news conference honoring the boy's memory.

Maryland's congressional delegation helped add a dental entitlement to the reauthorization of the State Children's Health Insurance Program, which covers children in slightly higher income groups than Medicaid does. The delegation also fought to get children's oral health care provisions into the federal health-care reform law, said Sen. Barbara Mikulski (D-Md.).

But millions of poor children are still going without care, according to a new report by the Government Accountability Office.

Report cards for states

A national report card by the Pew Charitable Trusts last year also took a dim view of progress. The District received a "D" and Virginia received a "C" on benchmarks such as getting dental care to Medicaid children and expanding the roles of dental hygienists or trying other ways to provide this care.

Work has continued to address the problems. In the District, a community partnership helped transform a crime-blighted liquor store into a dental clinic that opened in December for poor children living in wards 7 and 8, located east of the Anacostia River. The Howard University College of Dentistry is running a low-cost evening clinic for children whose parents are unable to get them to dental appointments during the day.

In Virginia, a federal grant has helped eight areas without adequate dental services expand preventive care and water fluoridation programs and provide loan repayment incentives to help attract dentists. Volunteer dentists, hygienists and dental assistants have set up free weekend clinics in rural areas of the state through a "Mission of Mercy" program organized by the Virginia Dental Association Foundation.

Maryland was one of only six states to receive an "A" on the report card. Since Deamonte died, the state has emerged as a national model of reform.

Under Gov. Martin O'Malley (D) and a new Dental Action Committee, the state's Medicaid dental system has been revamped. Medicaid reimbursement rates for dentists have been raised and paperwork reduced. The patchwork of insurers - including UnitedHealthcare - formerly responsible for getting care to poor children has been replaced by a single administrative service organization directly accountable to the state. An oral-health education campaign is being launched with a $1.2 million federal grant. Public-health hygienists have new freedom to work outside clinics. Physicians can now apply fluoride varnish to the teeth of Medicaid children who come to them for non-dental care.

According to state statistics, nearly 44 percent of children enrolled in Medicaid for any period during 2009 received at least one dental service, a sizable increase from just two years earlier. Dental funding for children and pregnant women increased from $42.5 million in 2007 to $137.6 million in 2010, reflecting both increases in the fees that dentists receive and greater numbers of patients, according to Maryland's 2010 annual legislative report on oral health.

First-day emergency

But many challenges remain. Though more than 1,000 of the state's roughly 4,000 active dentists are now participating in Medicaid, up 41 percent from 2007, there is still a shortage of care for the poor.

"If every dentist in Maryland joined Medicaid, you still probably couldn't meet the need," said Goodman, the state dental director. To his mind, such deficiencies call for safety-net clinics and public-private partnerships, and require innovative approaches that fit the communities they serve. That, said Goodman, is where the Deamonte Driver Dental Project fits in.

Backing from the National Dental Association, a minority dental organization, and a state grant of $288,000 helped get the project started in 2008. State funds and philanthropies have sustained it since.

Community activists and dental professionals such as Carver-Taylor chipped in, not only volunteering their professional skills but also helping raise money, in some cases a few dollars at a time: Carver-Taylor, who was a co-founder of the project, was part of a group that sold Mary Kay cosmetics to benefit the effort.

Nine schools were visited in 2009, using a rented van. Last year, the new mobile clinic was dedicated in Washington.

Since that day she telephoned the Foundation School, Hazel Harper has drastically cut back on her private practice and is now the project director, overseeing the program for a $40,000 annual salary. Teams of school nurses and counselors have been set up in 20 of Prince George's County's poorest schools to work with parents. Forty-seven "Dentists in Action" have volunteered to provide follow-up care and offer "dental homes" to children without places to go for regular visits. (The mobile clinic is not meant to be their regular site for dental care.)

Late in the morning at the Foundation School, a tall, slender 16-year-old, Marcus Johnson, appeared in the mobile clinic with a pain "like a needle stabbing me in my teeth."

Carver-Taylor and another volunteer dentist, Fred Clark, deemed his case a dental emergency. The boy's mother was called and he was swept off for immediate, free care by William Woodward, a Dentist in Action with an office nearby.

Meanwhile the children kept climbing aboard.

"Every time I turn around, there is another child," Clark marveled. "They keep popping up!"

The 50th child of the day was a girl who had been in Deamonte's grade. She was pretty, with sad eyes and five cavities.

Then Marcus Johnson returned with a smile on his face, the first stage of an emergency root canal completed and another appointment scheduled. By then it was time for the afternoon bell. The dental clinic on wheels, surrounded by school buses, looked like a huge exotic bird stranded among a flock of geese.

Weary and elated, Betty Thomas started closing things down. This day, the first day, was over. The work had just begun.