Native children in WA are disproportionately taken from their families. Advocates are working to change that

The story was originally published by the KUOW with support from our 2025 Child Welfare Impact Reporting Fund

Sarah Nenema and her 14-year-old daughter Shayna are portrayed hugging near where Shayna lives outside Spokane, on Thursday, April 24, 2025.

KUOW Photo/Eilís O'Neill

The day child welfare workers came to his house to take his kids away, James Nenema’s twins were 3.5 years old.

“I had to bring Kallen up to, you know, and put him in the…” James Nenema said, his voice breaking. “To have him screaming and not being able to do anything about it.”

After the twins were in the car, the social workers went to the middle school to get James Nenema’s daughter Shayna, who was 12 years old at the time. Shayna Nenema was on her way to a softball game, she said, when she got a note to go to the office and saw the child welfare workers’ car.

“I got to the office, and I was trying to tell my principal not to let them take me because I already knew who they [were],” Shayna said. “And they came in and sat down and tried talking to me, saying that they were just going to take me and that they already had my brothers in the car.”

Now, more than two years later, the Nenema children are still living with relatives, not their parents. They’re one of many Native families who have found themselves entangled in either tribal or state-run child welfare systems.

Native American children in Washington state are far more likely to be taken from their parents and placed in foster care than any other kids. That rate has remained stubbornly high, despite policy efforts to keep more families together.

Since the state enacted changes in 2023 to keep more families together, raising the bar for family separation, the number of children removed from their families overall has dropped by 10%, but the number of Black and Native American children separated from their parents has remained virtually unchanged. In the last year, 470 Native kids were removed from their Washington homes.

Experts say cultural misunderstandings and racial bias against Native American parents play a role. So do poverty and trauma, which make it more likely for parents to suffer from addiction or struggle with the demands of parenting.

Native Americans are also the most likely to have been separated from their own birth parents — and research shows that family separation can become an intergenerational cycle. For decades, the U.S. government systematically separated Native families and sent their children to abusive boarding schools, including in Washington state, traumatizing Native children and starting that cycle.

Some advocates say the best solution for most families is for the state never to get involved: for cases with Native American kids to be managed by their tribes. But for that to work, they add, tribal child welfare offices need more resources for programs that support parents who have experienced trauma.

Sarah Nenema is portrayed outside Spokane on Thursday, April 24, 2025.

KUOW Photo/Eilís O'Neill

An intergenerational cycle of separation

James Nenema and his wife Sarah have six kids, from ages 5 to 19.

“Deven — he’s like his mom,” James Nenema said. “He doesn’t like a lot of people around. Deshawn — he’s real quiet, but he loves sports. Shayna — she has a big heart. Jordan — he loves track. He’s fast. And the twins — well, those guys are real funny.”

Things have been really rough for the family in the past few years, Sarah Nenema said. First, they had a stillborn baby. A few months later, Sarah Nenema’s adoptive mom died, leaving her feeling unmoored.

“Right now, I feel completely alone,” she said. “I’m not close with my family. The last few people that I was close with I lost. So it’s been really rough.”

Sarah Nenema is from one of Washington’s coastal tribes, but her great-aunt raised her on the Kalispel Reservation, outside of Spokane.

After the deaths of her baby and her adoptive mom, Sarah Nenema struggled to cope. She and her husband were fighting all the time. For years, none of the kids went to the doctor. They didn’t enroll their son Jordan in school until he was 7. And their daughter Shayna missed roughly half her sixth grade year. The Nenemas say she was being bullied, so she would cry when they tried to make her go to school.

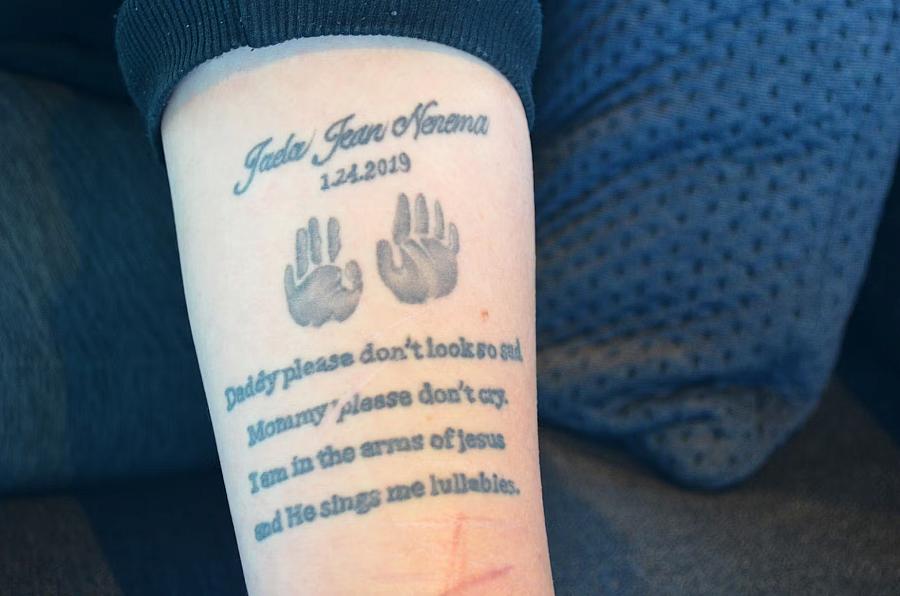

On Thursday, April 24, 2025, Sarah Nenema shows the tattoo she got for her stillborn daughter.

KUOW Photo/Eilís O'Neill

The Kalispel Tribe’s Indian Child Welfare office, which the Nenemas call ICW, got involved and charged them with medical and educational neglect. But they never offered help, James Nenema said.

“Their main thing of ICW is: Exhaust every option to keep your family together,” he said. “Offer, ‘What can we do? O.K., they're not making it to appointments. How can we help with that? Do you guys need rides?’ None of that. There was no effort at all to keep us together.”

KUOW spoke with a former case worker for the Kalispel Tribe who agreed her office should have offered more help.

A spokesperson for the tribe said she’s unable to comment on any specific cases but sent a written statement saying, “We are deeply committed to … providing [our families] with extensive resources and support.”

The statement added that the tribe focuses on keeping kids safe, but also on making every effort to reunify families.

James Nenema is portrayed outside Spokane on Friday, April 25, 2025.

KUOW Photo/Eilís O'Neill

Two child welfare systems

When it comes to Native kids, there are two paths their child welfare cases can take. There’s the state child welfare agency. Or many tribes, like the Kalispel Tribe, have their own child welfare offices that also have jurisdiction over their members. The Nenemas have never been in the state system, only in the Kalispel Tribe’s system.

“It’s so important when you have a Native child or youth in the system that tribes have control,” said Brooke Pinkham, an attorney at the Seattle University School of Law and an expert in Indian child welfare. “Because studies have shown time and time again [that] having connection to your culture is good medicine.”

Both systems have their drawbacks, Pinkham added, but the tribal system is preferable, even in cases where families are separated.

“One thing that tribes have really focused on is healing, creating spaces and ceremony, and, even within tribal courts, this healing process,” said Pinkham, a member of the Nez Perce who grew up in the Yakama Nation community. “A lot of tribes now have what's called healing to wellness courts.”

Healing to wellness

Amelia Blodgett DeLaCruz is a member of the Quinault Nation and a social worker who has worked for the tribe’s child welfare agencies and those of other tribes. She now works for the Quinault’s healing to wellness court and said it’s very helpful for families who are struggling with substance abuse.

“You’re [meeting] at such frequency that if something goes awry, then we have all the providers there to try to figure out, ‘What can we do to help this family get back on track?’” DeLaCruz said. “Instead of, ‘See you in six months and then we’ll get a pulse on how you’re doing and what you’ve accomplished in that time.’”

There are currently nine families using the Quinault’s healing to wellness court, and, DeLaCruz said, “We’re seeing a lot more success in their sobriety.”

DeLaCruz and others said the main thing tribal welfare systems need is more resources.

“Our families need a lot more support and end up being in the system a lot longer,” DeLaCruz said. “The funding needs to reflect that.”

Pinkham, the attorney at the Seattle University School of Law, said that tribal welfare systems need more resources for parents who have suffered from trauma.

That way, she said, “tribes can better take on and develop programs that meet the needs of those parents,” Pinkham said. “It is the responsibility of the federal and state governments to provide those resources through treaty obligations.”

Parents who, like Sarah Nenema, were raised outside of their own birth families are more likely to lose custody of their children. That’s in part because they can struggle to form stable, nurturing relationships in adulthood, so they need more support to become successful parents.

Even though tribal systems can lack resources, Pinkham said, the state system is worse for Native American families because, she said, it’s overcrowded and biased against them.

“There's just a lack of understanding of tribal cultures and tribal child-rearing standards, and also just racial bias,” Pinkham said. “And trying to apply state court norms to tribal cultural norms.”

State child welfare workers are supposed to consult with tribes in all cases involving Native American children, but Pinkham and DeLaCruz said that doesn’t always happen. DeLaCruz said the key is a true consultation that actually gives the tribe a role in decision-making, and it varies, depending on the region, whether that happens. In the case of the Quinault Nation, she said, the state child welfare department oversees cases involving Quinault children who are far from the reservation, adding that she values that partnership.

Washington state’s children and families department declined KUOW’s requests for an interview.

Over the past two years, the state has enacted two big policy changes. They’ve raised the bar for child removal: Social workers now have to demonstrate an imminent risk of harm before they can remove a child from their family. And the presence of drugs is no longer considered adequate grounds for removal.

Those policy changes have dramatically reduced the number of kids being separated from their birth families, but not the number of Native American and Black kids. And the state says its data do not include all of the kids overseen by tribal child welfare offices.

It’s unclear if, under the state’s new policies, there would have been grounds to take the Nenema children out of their home, based on the reasons and evidence provided in the court documents. But tribes don’t have to follow state policies; they can make their own determinations about what is best for children.

DeLaCruz said that’s a good thing.

“I've seen a lot of times where the state doesn't get involved in cases, and Quinault does, when there's drug use,” she said. “Parents are being sent home with the children from the hospital, and the children [are] testing positive.”

“We're knowing that family needs some resources, or they wouldn't be in that position,” DeLaCruz said. “Without intervention, how do they get the resources? Because [without intervention] there's no incentive for it. Keeping your child's a huge incentive to get resources to address mental health, substance use disorders, domestic violence — whatever brought the family to our attention.”

Sarah Nenema and her 14-year-old daughter Shayna are portrayed hugging near where Shayna lives outside Spokane, on Thursday, April 24, 2025.

KUOW Photo/Eilís O'Neill

Struggling apart

Of all the Nenema kids, Shayna is struggling the most with the family separation. She gets panic attacks where she struggles to breathe; she’s been to the ER for them. She’s withdrawn from friends and after-school activities.

“I don't play any sports anymore,” she said. “I just lost it all. I used to want to play sports in Cusick. I just felt safer out there.”

Cusick is the town where the family lived on the reservation. Now, the kids live outside Spokane.

Kalispel’s tribal court assigned all the Nenema children to different extended family — the twins with an aunt, Shayna with her grandfather. Research shows kids do better when placed with relatives, rather than strangers, for foster care. Still, all of them long to be back together as a nuclear family.

The Nenemas are working on the requirements for reunifying with their kids: parenting assessments, drug and alcohol treatment, counseling. It’s been two years of slow progress — sometimes a step forward, and sometimes another setback.

These days, they get unsupervised visits once a week. Sarah Nenema said she tries to plan hands-on activities.

“A lot of the time, it’s coloring or painting things or little science experiments that you can get at Walmart,” she said.

Last December, they made gingerbread houses. This April, they gathered for an Easter egg hunt.

“It's always really good when they're there,” Sarah Nenema said. “When we're all together, it feels normal.”