Northside: Being transformed into a healthy and thriving community

A Spartanburg, S.C., neighborhood once known primarily as a hotbed for violence and crime is now the home of a medical college and has attracted the attention of city officials, philanthropists and even a group connected to billionaire investor Warren Buffett.

Andrew Doughman wrote this series of articles for the Spartanburg Herald-Journal as a 2012 National Health Journalism Fellow. Other stories in the series include:

Northside: Story of the mill village is a familiar one

Northside: Single mom looks for college and a good job

Northside: Neighborhood's future depends on healthy choices

Northside: City is following Atlanta redevelopment plan

Spartanburg County Council considers fee-in-lieu of tax requests

Northside: Cleveland Elementary plays part in redevelopment

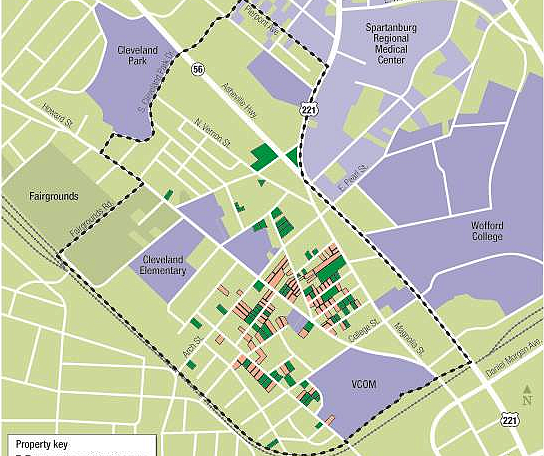

Northside neighborhood

The Northside neighborhood, once known primarily as a hotbed for violence and crime, is now the home of a medical college and has attracted the attention of city officials, philanthropists and even a group connected to billionaire investor Warren Buffett.

It is transforming from a violent inner-city area into a healthy and thriving community. This change has been in the works for several years. More than a decade ago, Spartanburg City Council built some single-family homes and made other housing improvements.

Better housing helped the neighborhood, but problems with drugs and crime persisted. Things began to change in 2009, when Spartanburg Public Safety established a team to work with city code enforcement to help shut down abandoned homes that were being used as drug dens.

In 2010, the Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine started renovating the old Spartan Mill on Howard Street to convert it into a new campus for the Carolinas. The campus opened in the fall of 2011. The $30 million new medical school encouraged city leaders to begin looking at ways to capitalize on that investment and further transform Spartanburg.

"Out of nowhere a school from Virginia decided to put a medical school in Spartanburg, South Carolina, and picked the most at-risk place they could possibly select," said Bill Barnet, chairman of the Northside Development Corp. "We decided that that was leverage enough … to take our community forward."

To help with the effort, Wofford College, Spartanburg Regional Healthcare System, the Mary Black and Spartanburg County foundations gave a total of $250,000, and local donors matched those contributions. Purpose Built Communities, an Atlanta-based firm is offering its consultant services for free with help from Buffett and other philanthropists, and the city has received a $300,000 federal grant to plan the project.

So far, more than $4 million has been dedicated to this square mile of land north of downtown.

Leaders are focusing on building a healthier community and reversing a decades-long trend of out-migration from the inner city. To get there, city officials and their partners embarked on an initiative this month to craft an ambitious redevelopment plan. It centers around building mixed-income housing, improving the neighborhood's elementary school and encouraging banks, grocers, retailers and social service providers to move back to the area.

While the Northside still has pockets of poverty, the mission is not to replicate past efforts in which the Spartanburg Housing Authority and the city demolished and rebuilt public housing complexes. Instead, the city has created a nonprofit led by former Spartanburg mayor Barnet, the Northside Development Corp. This group is buying wide swaths of land and working with the area's elementary school, the Cleveland Academy of Leadership and other partners to improve not only the quality of the housing stock but the entire health of the neighborhood.

"Research now is quite clear that your ZIP code dictates more about how healthy you are than potentially any other factor of your life choices," said Curt McPhail, project coordinator for the Northside Development Corp. "So for us, creating a healthy, vibrant Northside that people choose to live in and choose to stay in will only impact the individual health, the neighborhood health and the city's health in the broadest and most specific senses."

Buying land

Property is selling fast in the area. The Northside Development Corp. and the city have bought more than 100 vacant or condemned houses.

"We've tried to buy up those lots so that nobody could take property and do something with it that we didn't think was consistent with the ultimate health and welfare of the residents," Barnet said.

After the deals close, wrecking crews move in to demolish the eyesores.

The square mile comprises less than a fraction of the city.

During the past four years, the city has spent just under half, or $782,034, of its citywide demolition-related budget there.

Almost 1,000 people moved out of the greater Northside area between 2000 and 2010, a 19 percent drop in population, according to census data. Nearly one in every four houses is vacant.

A walk down Weldon Street in the Northside is like taking a walk in a nature preserve. The residential street no longer has a single occupied house. It's a sobering example of the hollowing out of the Northside in the wake of Spartan Mill's closing in 2001 and the destruction wrought in the 2008 foreclosure crisis, as well as an example of the blank slate upon which neighborhood and city leaders can dream of a vibrant, better future.

"We have an opportunity to really work hand in hand, everybody, to recreate Northside in a way that we're all proud of," McPhail said.

While the city and its partners have brought a diverse group of civic, nonprofit, health and academic institutions to the table, they also need the support of neighbors.

Calling himself a "watchdog," the Rev. Walter Belton, pastor of St. Paul Missionary Baptist Church in the Northside, said the community does not want to feel like "rich white men" are pushing a project on them.

Instead, neighbors need to buy into the project, have a place at the table, and ultimately ensure that they are not displaced during the redevelopment work, he said.

"The resource of the community is the people, and if you lose the people, you lose the community," Belton said. "New homes don't make a community. It's the individuals."

This story was originally published at GoUpstate.com on January 26, 2013

Photo Credit: GARY KYLE