Opioid Overdoses Are At Record Highs. It Doesn't Have To Be This Way.

This article is part one of a reporting series by Ariel Boone for Street Spirit and KPFA Radio with a USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2021 California Fellowship.

Her other stories include:

Part 2: Alameda County Doesn't Track Deaths of Unhoused People - Here's Why that Impacts the Opioid Crisis

Special report on opioid crisis in Oakland’s unhoused community: Voices of overdose and survival

Michaella Jones hands out sterile supplies from the HEPPAC mobile outreach vehicle in April 2020. HEPPAC is one of few syringe exchange programs in Alameda County, and sends teams into neighborhoods to reach unhoused people who use drugs.

(Ariel Boone)

When Thad regained consciousness, the lighting looked different and his body hurt. He remembers getting up and walking around his encampment, where a friend called out to him and told him he looked ill. He was overcome by nausea and vomited in a port-a-potty, then tried to lay down.

He had just survived his first opioid overdose after smoking fentanyl. The woman he smoked with administered the overdose reversal drug Narcan, to revive him and restart his breathing. Now he was in withdrawal.

“It was kind of scary afterwards to think about it, because I’d seen it happen to other people,” Thad says.

Thad is one of thousands of unhoused people who deal with substance use in Alameda County. He faces triple crises: homelessness, pandemic, and now, an overdose surge that has reached historic levels.

Approximately 50,000 people died in the United States from opioid overdoses in 2019, before the U.S. entered Covid lockdown. Provisionally, the CDC estimates that number grew to 69,000 people in 2020. In California, deaths from opioid overdoses increased 72 percent during the 12 month period between February 2020 and January 2021, over the previous year.

To better understand the overdose crisis, Street Spirit spoke to over two dozen people over the course of 16 months, including unhoused people who use drugs, harm reduction advocates, county employees, and medical providers. We followed outreach workers in North, East and West Oakland who are on the frontlines of the overdose crisis: distributing life-preserving supplies and services to people who use drugs, and advocating for the structural change they believe could prevent overdose altogether and provide dignity for people on the street.

PART I—COMPOUNDING CRISES: COVID FANS THE FLAMES OF OVERDOSE

When the Bay Area went into pandemic lockdown in March 2020, Thad was 34, living unsheltered in Oakland, and using opioids. “They told us to stay within our isolated group as much as possible and not to interact with other camps, which is somewhat impossible when you’re trying to have money, and as a drug addict,” says Thad. “I felt kind of alone, or like we were just going to be left behind.”

It took two months of agitation and pressure from residents and social workers to get the city to install hand-washing stations where he was staying. A thought crossed Thad’s mind: Oh. We’re screwed.

Housing is inseparable from the overdose crisis. In the most recent Alameda County Point-In-Time Count in 2019, 30 percent of unhoused people surveyed said they deal with drug or alcohol use. Crucially, not all unhoused people use drugs. But for those who do, living unsheltered is often a catalyst. Being exposed to ongoing trauma can trigger drug use, or drug use at increased amounts.

“People can get lost in alcohol, drugs, anything and everything, because this is not a human way of living,” says an unhoused Berkeley resident named Ana, whose friend was found dead from a suspected overdose in June. “We need to be intoxicated in order to endure what we endure.”

The national rates of opioid overdose have never been higher, and during the pandemic, the crisis measurably worsened. Across the United States, death rates from opioids seemed to stabilize and even decline slightly from 2017 to 2018. In fall of 2019, they began to climb. And by March of 2020, they started to skyrocket.

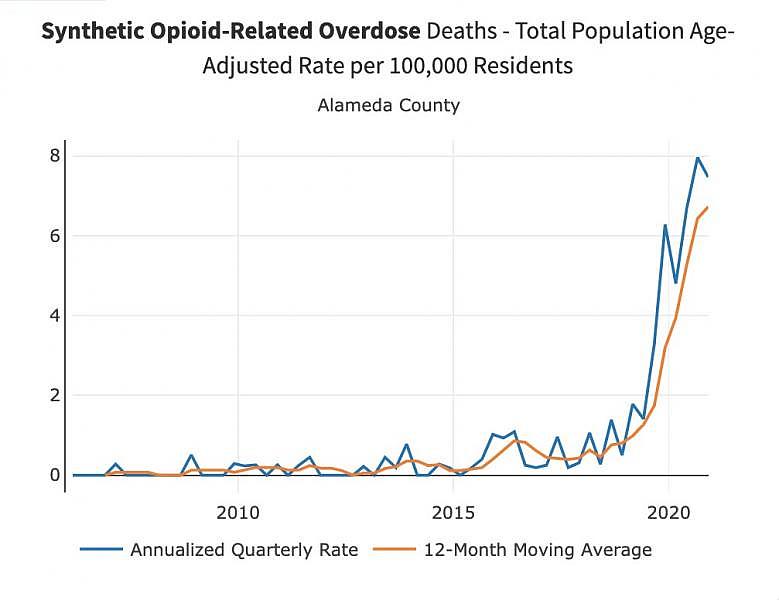

In Alameda County, the data shows the same: deaths and emergency department visits from opioid overdose have continued to rise, spiking at the end of 2019 and in the months when COVID lockdowns began.

This is no coincidence.

Savannah O’Neill has her finger on the pulse of overdose prevention across the United States. And in early 2020, she was nervous about an upswing in overdoses and deaths.

At the National Harm Reduction Coalition, O’Neill works to expand free syringe programs and services for people using drugs across California. She worried that social distancing requirements and fear of COVID could drive people to use drugs alone instead of with friends or in groups. Using alone means nobody would be present to revive someone from an overdose with the medication Narcan.

“We’re not here to just provide a service. We want to be a part of the community and we want to give people the resources that they need to survive”

COVID pulled the rug out from under vulnerable communities, advocates say. Unhoused community members who were previously staying on the couches of friends or family may have been asked to leave when the virus hit. Libraries closed, and along with them, bathrooms and charging outlets disappeared, as did places for unhoused people to shower and do laundry.

“All of us, regardless of drug use, rely on routine to keep ourselves stable. And when that gets interrupted, that’s scary for overdose risks, for increased drug use, for different kinds of drug use, riskier behavior,” O’Neill explains. Without wireless internet and a place to charge up, how can an unhoused person attend a 12-step meeting for addiction that now takes place online?

Plus, the pandemic is a collectively traumatizing experience, she told Street Spirit. “And what we know about trauma and drug use is that they’re really linked together.” Traumatic events, isolation, job loss, the death of loved ones—all these things can trigger drug use, both for people who use drugs and those who have been sober for years.

But it’s not just the pandemic. The drugs on the street are also changing.

A closer look at fentanyl

Everyone agrees fentanyl is a core cause of the overdose crisis. It’s a pain reliever developed in 1959, now commonly prescribed in hospitals for severe pain and surgery recovery. But almost all of the street supply is made in illicit labs with components manufactured in other countries, including China, Mexico, and India.

Around 40 times more potent than heroin and up to 100 times more potent than morphine, fentanyl is available for purchase in the Bay Area and penetrates the supply of other drugs.

A viral image circulated by police departments shows vials of salt labeled heroin, fentanyl, and carfentanil—a more powerful relative of fentanyl—with similar potent doses of each. Next to the spoonful of “heroin,” the fentanyl and carfentanil look like grains of sand. The message is: It takes much less fentanyl and carfentanil to get you high. And in the Bay Area, it’s increasingly concealed in the street supply of pressed pills, as well as stimulants like meth and cocaine.

Thad points out fentanyl is “cheaper than a heroin addiction,” and speculates that with widespread and increased poverty during the pandemic, more people are choosing to use it. In other words, as fentanyl and other synthetic drugs bleed into the drug supply, people begin to regularly use them, too.

Thad first started using fentanyl in early 2020. The second or third time he smoked it, he says, he overdosed.

An overdose occurs when the physiological effects of a drug exceeds the body’s tolerance, overwhelming the body’s ability to keep itself alive. During an opioid overdose, a person’s breathing becomes shallow and slow. Oxygen levels drop dangerously. But overdose does not always end in death—there’s a window of time after someone takes a fatal dose of opioids where the drug naloxone can revive a person. Narcan immediately puts that person into withdrawal, evicting the opioids from receptors in the brain and taking their place for 30 to 90 minutes.

“I’ve overdosed three times in the last year to where I had to be Narcanned back to life,” Thad tells Street Spirit. “I probably would have died for sure, just from inhaling a tiny bit of smoke. It’s crazy.”

He thinks he likely overdosed as a result of accidentally mixing fentanyl and alcohol all three times. I ask Thad if he carries naloxone, and he produces a red pouch from beneath his shirt, hanging around his neck. The medication is zipped inside—he brings it everywhere.

Some longtime drug users may choose fentanyl after building a tolerance to other opioids.

“The reason why I use fentanyl is because I got tired of using needles,” says Kory, an unhoused resident of West Oakland who works as a sign flyer, twirling business advertisements to passers-by.

Over time, it became harder on Kory’s body to inject heroin. “If I were to try smoking heroin, that’s not fulfilling at all. But when I smoke fentanyl, I actually feel it,” he says, “and the needle thing has become just a nightmare when you don’t have veins.”

But despite using fentanyl himself, he wants to warn others not to start using it, saying it is very dangerous for anyone who is not a longtime user. “Keep some Narcan on you,” Kory urges. “You might save a life.”

Thad told Street Spirit he hopes to stop using fentanyl and try medication-assisted treatment. He describes using fentanyl as “kind of like straddling death. It’s the end of the road,” he says. “It’s tightrope-walking death, you know, to get high.”

Synthetic opioids like fentanyl have driven the increase in fatalities in recent years, representing 83 percent of fatal opioid overdoses in the United States in the 12 months ending in January 2021. In comparison, fatalities from heroin have stayed relatively constant, even declining, since 2015.

In Alameda County, the numbers show the same. In the latest data available, the fatal overdose rate from synthetic opioids just goes up, and up, and up.

Opioid-related deaths, which have been steadily climbing, skyrocketed as COVID swept the county. (California Opioid Overdose Surveillance Dashboard, accessed September 2021)

In the beginning of 2020, the Alameda County Public Health Department released a fentanyl overdose health advisory, which reported “an increasing number of suspected fentanyl overdoses among persons without a history of opioid use, such as cocaine and methamphetamine users.”

At this point, any street-purchased drugs could contain fentanyl, the county says. This means that many people are consuming fentanyl unintentionally, which often leads to overdose. Seth Gomez, senior pharmacist with Alameda County Healthcare for the Homeless, says the risk factors for an overdose now include using “any drug that is acquired from the street,” including both “hard drugs” and street drugs that appear to be prescription products like Xanax.

“I think it’s in all the drug supply,” confirms Katie O’Bryant, an outreach worker with West Oakland Punks With Lunch, a volunteer harm reduction group that hands out safer drug use supplies, hygiene goods, food, and Narcan to unhoused people like Thad and Kory.

“A lot of people say it’s just been stepped on more, it’s not as good,” says the group’s founder, Ale Del Pinal. “Stepped on” connotes additives or unwanted substances being cut into someone’s drugs.

“People are overdosing, and it’s just a shame because it’s not necessary,” Del Pinal adds.

Overdose is not the necessary conclusion of drug use, advocates like Del Pinal say. The harm reduction supplies the Punks pass out, such as Narcan, provide a strong defense against the increasingly unpredictable drug supply—and give people the tools they need to survive so they can choose how they want to live their lives—a choice advocates believe belongs to each of us.

PART II—WHAT IS BEING DONE?

Community members collect supplies from HEPPAC in Fruitvale. (Ariel Boone)

In April 2020, Michaella Jones sat in an RV wearing two masks and sterile gloves, holding clean biohazard containers for used syringes, ready for her next visitor. A line of nine people stretched from the RV parked in a cul-de-sac in Fruitvale to an auto-repair parking lot across the street.

Jones is the coordinator for overdose prevention, education, and naloxone distribution with HEPPAC, the HIV Education and Prevention Project of Alameda County. Throughout the week, HEPPAC dispatches workers in Oakland and Contra Costa County to distribute supplies, with the stated goal of curbing HIV and Hepatitis C transmission in the East Bay among people who use drugs. They are one in a small group of syringe exchange programs in Alameda County that hit the streets to deliver services in historically excluded and disenfranchised neighborhoods.

Harm reduction groups provide a critical service — health supplies, delivered without judgment, in neighborhoods that most need them. “I think they’re doing great work,” says Oakland resident LG, who gets supplies from Punks With Lunch. “They have the attitude of a proletariat worker. They take you palms up, how you are.”

A woman pulls up in a car next to the HEPPAC line. “Hey, Grandpa!” she calls out. An older man holding a brown paper bag of supplies waves to her, gets in the car, and they drive off together. Another woman stands in line to get condoms for her granddaughters. Some arrive on bicycles, others on foot or in cars with friends.

The line moves quickly as the sun sets. In the shadow of 880 and BART, more than five dozen people stop by the mobile supply station over two hours, receiving syringes, Narcan, pipes, and wellness supplies, including tinctures and balms for skin wounds from injection drug use. COVID-19 is spread through saliva, so advocates want people to avoid sharing pipes when smoking. “It’s pipe week!,” a sign proclaims to those standing in line.

While the pandemic brought unprecedented times to unhoused people who use drugs, harm reduction organizations have had to work on overdrive to keep up. West Oakland Punks With Lunch has noticed a major uptick in need for the services they provide. Founder Ale Del Pinal told Street Spirit that in one week toward the beginning of the pandemic, volunteers gave out 16,000 syringes, around double their typical distribution at that point, and many more boxes of Narcan.

And harm reduction organizations know participants are using the Narcan they distribute. “For a while, we were seeing a huge uptick in overdose reversals reported. I think we saw over 20 in one week, which was really crazy,” Del Pinal says.

Education about overdose prevention had to change to keep up with the pandemic as well. An anonymously-produced zine, “Harm Reduction for People Who Use Drugs and Don’t Wanna Get Sick With Covid-19,” gave practical advice: Stock up on drugs if you are worried about the supply being interrupted; gather health supplies to cope with withdrawal symptoms; ask medical providers for extra months of take-home prescriptions for treatment medication. It also suggested asking suppliers not to carry drug baggies in their mouths and advised against sharing pipes and bongs.

Braunz E. Courtney is the executive director of HEPPAC. “Bringing the services right to where the people are at, that’s what our bread and butter is,” Courtney says. “To get in the streets and say, ‘Hey, if you’re going to do this, this is the safest way to do that.'”

Braunz E. Courtney sits on the steps of Oakland’s Oscar Grant Plaza on August 31—HEPPAC set up a booth to commemorate International Overdose Awareness Day, giving out free food and hosting Narcan trainings. (Courtesy of HEPPAC)

Courtney celebrates any actions people take to keep themselves safe while using drugs. “Even if you’re in your most chaotic stage of use, and everything is about getting that high, getting that drug, the fact that you’re coming to the needle exchange shows that you’re taking care of yourself,” he says. “That shows that you care enough about your health, despite what others stigmatize you as being a substance user.”

This outlook saves lives.

But government decision-making often obstructs advocates’ efforts. There’s a reason that the use and manufacture of drugs are forced underground, where drugs can be altered or cut with other substances: the war on drugs. Drug laws punish people who use drugs, and unhoused people are constantly targets for arrest.

“The war on drugs impacts our folks severely,” says Del Pinal. “They are the most impacted. They’re the ones who are suffering from infections. … All the powers that be that perpetuate stigma, that perpetuate the criminalization of people who use drugs, the criminalization of drugs themselves—that is at the root and what is to blame, and inequity in general.”

PART III—IS THE GOVERNMENT DOING EVERYTHING IT CAN TO SAVE LIVES?

As the overdose crisis escalated during the pandemic, government officials loosened certain restrictions on accessing sterile supplies and drug treatment at the local and federal level.

According to HEPPAC, Contra Costa County lifted a limit on syringe distribution during COVID that previously required community members to present a used syringe for each sterile syringe received.

Both the state of California and Alameda County elected not to require emergency COVID housing to be “dry”: shelter in place motels allowed residents to drink and use drugs.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, part of the federal government, loosened certification restrictions for clinicians who wish to prescribe the opioid addiction treatment drug buprenorphine and allowed it to be prescribed through telemedicine for the first time during COVID.

But the changes were small, and the overdose crisis was outsize.

Data shows buprenorphine prescriptions have actually decreased across Alameda County since the end of 2019, suggesting people with opioid use disorder still face significant barriers to accessing treatment that these federal changes did not remedy.

Easing these rules only scratched the surface of the kind of holistic interventions necessary to curb the overdose crisis—like devoting more money to harm reduction groups like West Oakland Punks With Lunch and HEPPAC.

Opioid overdose rescue kits are distributed during HEPPAC outreach in Fruitvale. (Ariel Boone)

Even in the face of the most severe overdose crisis in recent history, harm reduction services struggle for funds and political ground. Syringe exchange programs are outright illegal in eleven states, a legacy of the Reagan era and punitive laws passed in the 1980s.

In California, some Democrats have dragged their feet to support people who use drugs.

In 2019, harm reduction advocates won $15.2 million in state funding that helped to hire vital staff for syringe access programs in rural and underserved areas. The money was approved by Governor Gavin Newsom—a move that harm reduction advocates call a huge win. Just one year before in 2018, Newsom’s predecessor Governor Jerry Brown denied the request and vetoed a bill that would have allowed San Francisco to open the first government-sanctioned supervised drug consumption site in the country, where medical staff would be on hand to respond to overdoses.

Brown’s veto of the drug consumption site bill was scathing. He wrote that “enabling illegal and destructive drug use will never work” and endorsed punitive measures to force people who use drugs into treatment programs. He called the idea of safe sites “all carrot and no stick,” dehumanizing language that seemed to echo the policies of the drug war.

State lawmakers had another shot at passing safe consumption legislation this year through SB 57, introduced by Senator Scott Wiener, which would have allowed for supervised drug consumption locations in San Francisco, Oakland, and Los Angeles. But the Assembly Health Committee in July postponed the bill’s hearing until 2022, delaying the process by an entire year — disappointingly for advocates, it means the first site wouldn’t open before 2023, unless cities or counties choose to defy the state and act proactively.

Meanwhile, the federal government’s drug enforcement policies could determine the fate of safe consumption sites. The Trump administration threatened to criminally prosecute any cities who open such locations, suing a Philadelphia nonprofit that planned to open a site.

It’s not yet clear what President Biden will do. The new administration released a list of its drug control priorities to Congress in March, which included “enhancing evidence-based harm reduction efforts.” But Biden also extended a little-known policy that preemptively criminalizes people who possess, make, or sell synthetic opioids related to fentanyl. Advocates say it’s a continuation of failed policies of the war on drugs. And federal arrest data so far shows that the people being convicted for fentanyl charges are disproportionately Black.

It’s not just a matter of drug enforcement policies. In order to meaningfully reduce overdose in the U.S., state and federal legislators would also need to turn their attention to the affordable housing crisis. At the Harm Reduction Coalition, Savannah O’Neill says housing is “probably the thing that is most asked for” by participants in harm reduction programs, and “would make the broadest difference in people’s lives.” Unfortunately, it’s also a resource that most harm reduction groups are not able to provide. And in Congress, no large-scale relief is in sight for the half-million unhoused people in the United States.

During an outreach walk with West Oakland Punks With Lunch, a Black community member named Indiana stopped by on his bicycle to pick up food, hygiene, and safer drug use supplies for himself and his girlfriend. They live in an encampment in North Oakland. I asked him how the pandemic has been for him.

“This has been going on before. This is the pandemic,” he says, holding his supplies and gesturing to the tents up and down the block. “Prepare yourself for doom,” he finishes wryly.

The death rates in Alameda County for overdose are twice as high for African-Americans as whites. To explain this, county senior pharmacist Seth Gomez points to the disproportionate rates of homelessness for Black people in Alameda County. In 2019, Black residents made up 47 percent of Alameda County’s 8,000-plus unhoused population, compared to 11 percent of the population overall. Several unhoused Black community members who use drugs told Street Spirit the same: Black residents are more likely to be unhoused than anyone else in Oakland, being unhoused exposes you to additional trauma, and trauma is linked to drug use.

If the U.S. didn’t have such an enormous crisis of homelessness, exposing hundreds of thousands to the stresses of being unsheltered, the overdose crisis would look significantly different. Together, government action to immediately and permanently house people, an end to the war on drugs, and more funding for street outreach programs would open the door to the interventions that could meaningfully prevent overdose.

The Punks With Lunch office in West Oakland where the group meets to organize, and stores their harm reduction supplies. (Ariel Boone)

But as long as this political morass remains the status quo, grassroots harm reduction groups and their participants struggle to hold the mounting weight of the crisis.

Katie O’Bryant of Punks With Lunch says she dreams of a safer drug supply and the ability to test drugs widely.

“If drugs were legalized—if I’m dreaming big—and people could have absolutely safe supply, that would be a beautiful thing. It would save so many lives, and it would also improve the quality of people’s lives so, so much, so drastically.”

In the absence of these reforms, community members rely on each other to stay safe. The West Oakland Punks With Lunch warehouse has bins stacked high with syringes, masks, pipes, shelf-stable food and condiments, sanitizing wipes, biohazard containers, and informational flyers. Above the kitchen, a poster hangs with the words “Participants saving lives.” That’s central to their ethos.

“We’re not here to just provide a service. We want to be a part of the community and we want to give people the resources that they need to survive,” Ale Del Pinal explains.

“Literally, it’s life and death. And it takes the community to take care of themselves.”

**

CORRECTION: The print version of this story stated that the overdose deaths in Berkeley’s civic center park were in July, rather than June. We have corrected the error in the web version of this story.

This article is part one of a reporting series for Street Spirit and KPFA Radio with a USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2021 California Fellowship.

Ariel Boone is a freelance journalist and reporter for KPFA Radio in Oakland, California. Ariel previously worked at Democracy Now! in New York.

[This article was originallly published by The Street Spirit.]

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change