Orange County park history is a tale of two counties

This is Part 1 of a series that explains the scarcity of parkland spaces in Orange County, Calif.

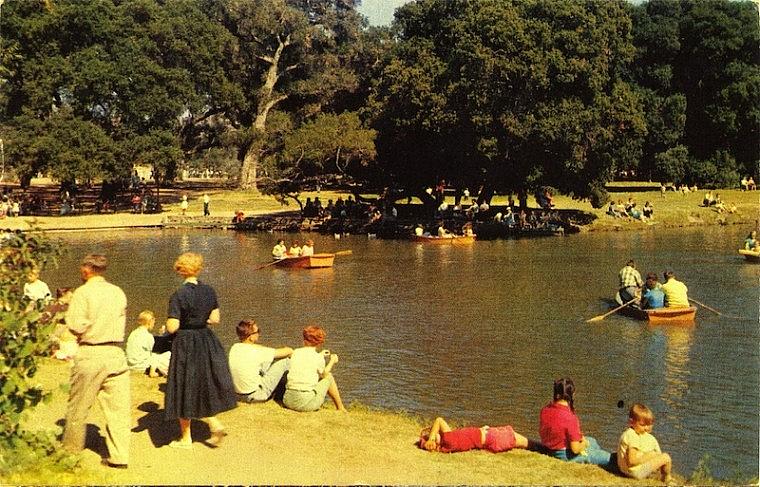

Irvine Park circa 1957. Parks have been a far bigger part of the development of South Orange County than in the north.

In the early 1960s, while Southern California was experiencing a building boom unlike it had ever seen before, or ever will again, an Orange County supervisor and a county planner secretly worked on a project they dared not reveal even to their colleagues for fear it would be scuttled.

They worked nights and weekends, drafting plans and scheming to get around a political establishment, led by the local newspaper, that would likely act to quash their project.

The supervisor was the late David Baker, and the planner was Richard Ramella.

Their secret project? A park.

Ramella and Baker beat the odds, and their park was created in Fountain Valley in 1967. It was named Mile Square Park, and today it is one of the county's most used and best loved parks.

"It was done in total secrecy, and one man was responsible for it — Dave Baker," said Ramella, who lives in Newport Beach.

The story of Mile Square Park is a window into Orange County's political and policy mindset as its northern half was developed at a breakneck pace throughout the 1950s and 1960s. And it helps explain why today there is such a disparity of parkland in the north of the county versus the south.

"You look at Orange County from the air and you see two very distinct areas," Ramella said. Most of Orange County north of the 55 freeway is a grid of housing tracts while South County's highways curve through and around acres of open space.

"It's two different counties," Ramella said.

Most cities try to have four acres of neighborhood parks for every 1,000 residents, and north Orange County generally falls far short of that goal. Northern cities have more than three times as many people per park acre than cities in the south, according to the Center for Demographic Research at Cal State Fullerton.

In Stanton, there is just one acre of park for every 1,830 people. Santa Ana's ratio isn't much better — 1,271 people per city acre of park.

"There was no foresight for open space," said Jim Box, assistant city manager and director of parks and recreation for Stanton.

The planners of South County, meanwhile, made parks a high priority. Development plans followed the contours of the hills and valleys, and determined efforts were made to maintain areas of open space. The numbers bear this out. The cities of Irvine, Laguna Niguel and Lake Forrest, among others, have more than seven acres of parkland per 1,000 people.

The consequences of this disparity go far beyond aesthetics. Health in a community can be directly affected by the amount of neighborhood parkland. Not just acreage statistics matter. Community parks need to be within a short walk for residents to benefit.

According to research, adults in a neighborhood without safe, nearby, outdoor space are more sedentary, more stressed and more overweight, leading to higher health insurance rates. And children who live without parks pay less attention in school and have more obesity and even eyesight problems than those who can play outside on grass and among trees.

Then there's the self-interest factor. Economic researchers at Texas A&M University have confirmed what community designers knew 200 years ago: that safe, usable park space increases the property values of surrounding neighborhoods.

So how did North County neighborhoods become so park poor and South County so park rich?

Orange Groves to Asphalt

In many respects, the history of Orange County development is the history of Ramella's career, a journey that began with the citrus groves and flat agricultural fields of northern Orange County.

Ramella, a fourth generation resident of Orange County, became one of Southern California's foremost urban designers. In the years before the 1950s, when he was growing up in Anaheim, the county had 13 incorporated cities, fewer than half today's 34.

The county's population in 1950 was about 216,000. Ten years later it had more than tripled to 704,000, and by 1970 it had doubled again to an estimated 1.43 million people.

Satisfying the demand for housing came before all other community needs during these years. The county was a developer's paradise. Ten cities incorporated within 10 years. Farms in Orange County were converted to housing tracts at the fastest rate in the nation, according to county historians.

Development interests held sway on the Board of Supervisors, and the deeply conservative owner of the local newspaper decried spending tax dollars on almost anything other than protecting private property.

The pace of development was so out of control that at one point, county staffers gave up trying to plan most of north Orange County, Ramella said.

It was a boom beyond anything county or city government could have imagined, said county Assistant Archivist Chris Jepsen. "Nobody knew what they were in for."

In 1950, the county issued 5,542 building permits. In 1955, the year Disneyland opened, the number had increased fivefold to 25,889.

As fast as county officials approved housing tracts, leaders of existing North County cities raced to annex them, Ramella recalled. City leaders, like their county counterparts, didn't consider the lack of neighborhood parks in their drive to grow.

Stanton, La Palma, Garden Grove and Westminster were founded between 1953 and 1962. Today, these cities are four of the five most park-poor in Orange County, each having less than one acre of park per 1,000 people.

The Well-Known Positives of Parks

At the time those cities were being developed, the importance of neighborhood parks, both from health and economic perspectives, had been common knowledge for well over a century.

In 1833, cities in England were urged by the Parliamentary Select Committee on Public Walks to create parks because they helped protect the health of residents, among other things serving as breaks between areas that could hinder spread of infectious diseases.

Two decades later in 1856, New York City Comptroller Frederick Law Olmstead proposed creation of what became 843-acre Central Park, arguing, in part, that it would more than pay for itself by increasing the surrounding land values and thereby bringing the city more tax revenue.

Ray Watson, an Orange County newcomer in 1965 who went on to become president of the Irvine Co., said he studied the beneficial effects of parks on communities while a student in the early 1950s at the University of California, Berkeley.

According to a history compiled by the Orange County Parks Department, early German settlers in Anaheim in 1857 began recreational use of an oak grove on part of Don Teodosio Yorba's Rancho Lomas de Santiago.

The area became so popular that "as the nearby communities grew, the 'Picnic Grounds' became a mecca for valley dwellers, and with organized festivities on May Day and the Fourth of July," according to the county history.

The 160-acre oak grove became Irvine Park and California's first regional park after rancher James Irvine sold the land to the county for $1 in 1897. Eleven years later, the Trabuco Canyon Reserve was designated the Cleveland National Forest. And the O'Neill family donated land for another regional park in South County.

Anaheim, incorporated as a city in 1870 when Orange County still was part of Los Angeles County, created its first park, Pearson Park, with a bond issue in 1920. Hewes Park east of Orange came into being around 1905, and Santa Ana's Birch Park existed by then.

But the park ethic that existed in Orange County up to World War II was not apparent in the 1950s. The reasons, according to those who were there, was a county bureaucracy still in its infancy, a developer-friendly Board of Supervisors and an influential newspaper publisher hostile to all but a narrow range of public investment.

Before roughly 1959, Orange County housing tracts didn't require much more than the approval of a county engineer and the Board of Supervisors. And during the early stages of the building boom, each of the county's eight departments reported directly to one of the five supervisors.

Reporters and others who worked around the county at the time said the system led to competition among the supervisors to help the departments under them, which could translate into benefits at election time when one might campaign as "Mr. Airport" or another as the county's expert on roads.

But there was no "Mr. Park," not even a county parks department.

Another reality of that era is that supervisors tended to be farmers with little development experience or businessmen who sympathized with the problems and risks facing developers. According to a former state assemblyman, developers throughout Southern California generally opposed providing land for any public purpose, including sidewalks, much less parks.

As Watson said, developers didn't like to give up land for parks "if they didn't get paid for it. A guy who buys 200 acres isn't going to want too many parks in his 200 acres."

Then there was R.C. Hoiles, publisher of the Santa Ana Register. Hoiles wrote a regular column that asserted his opposition to public schools, the minimum wage and the United Nations, among other issues. Government, he argued, shouldn't tell private property owners how to use their property.

Ramella said that in late 1960, he and other members of the county Planning Department gathered around a map of housing tracts in the northwest part of the county, and "we said to ourselves 'there's no hope. There's nothing we can do. It's too late.'"

The Mile Square Miracle

But there was one ray of hope.

Ramella was working as a planner with offices in the county Engineering Department in the early 1960s when Baker, a county engineer, took an interest in his work. Later Baker challenged entrenched incumbent Supervisor Willis Warner of Huntington Beach for a seat on the Board of Supervisors.

"David Baker ran on the platform of providing regional parks in Orange County, and he won," said Ramella.

Once he'd been in office for a while, Baker contacted Ramella "and said he'd just come back from Washington, D.C., and talked to the Navy about the possibility of buying" some land that was a World War II airfield and later a Navy training area.

Ramella worked nights and weekends developing the plans in order to avoid arousing opposition. He said Baker was particularly concerned about keeping the Register from finding out, fearing the paper would stir up so much opposition it would scuttle the plan.

Ramella's proposal was presented to the Navy and later the Interior Department for approval. In 1967, the county got Mile Square Park on a $1 lease for 100 years.

The park stands today as an exception: a regional park that is accessible to both urban and suburban residents of North Orange County.

"Mile Square Park was a difference maker," said Tom Daly, a former Anaheim mayor of Anaheim and current Orange County recorder. "Anybody who tried to get rid of Mile Square Park [today] would be run out of town on a rail."

Go South, Young Park Planner

The early to mid 1960s turned out to be a pivotal period in Orange County officialdom's mindset about parks. As development moved south, planners began acting on a decade of lessons learned. They were aided by a statewide awakening to what the rapacious development of the 1950s had done to California.

Ramella remembers the Orange County Chamber of Commerce going to the Board of Supervisors at some point in the early 1960s and saying, "We need regional parks in Orange County."

At that time the county had just two regional parks, the original Orange County Park (now Irvine Park) and O'Neill Park, donated by the family that owned Rancho Mission Viejo.

The Board of Supervisors appointed a committee to study the issue. "Normally," Ramella noted, "that's the worst thing you'd want them to do."

But in this case, he said, it served the county well.

The reason, he said, is that committee members were the heads of all major departments concerned with park lands, including harbors, fire, road, real estate and planning departments. Rather than competing with each other, they were strongly unified, Ramella said.

With so many department heads presenting a united front, he said, the committee was able to persuade supervisors to adopt a standard for parkland — about 10 acres of recreational land for every 1,000 county residents. The county agreed to supply six acres if cities would put in the remaining four.

That meant that as South County developed, neighborhood parks and green spaces would be included in plans. Additionally, the county began acquiring and setting aside land for a regional park system.

Today, Orange County has 13 regional parks, seven wilderness parks and seven historic parks totaling 60,000 acres. The county also manages seven miles of beaches along the coast.

Another key moment came in 1975, when the state Legislature, reacting to overdevelopment problems throughout California, passed the Quimby Act, which requires developers to set aside land for parks or pay fees for park improvements. The law required cities and counties to have a master plan that includes parks.

John Quimby, a former Democratic Assemblyman from San Bernardino, said he authored the law because he was a city councilman in the 1960s and saw firsthand the need for parks.

"We couldn't get the goddamned developers to budge an inch" on dedicating land for public use, including putting in sidewalks, he said.

Developers heatedly opposed his legislation, he said, but the irony is that "it turned out that developers liked the bill afterwards, because they found out that [having parks] legitimately increased the value of the houses."

The Importance of Irvine

Another strong influence on development of South County was the Irvine Ranch. The ranch's northwest boundary, generally along the 55 Freeway from Newport Beach to the mountains, created a natural dead end for development coming from the north.

The worst of the North County development was underway when Watson moved to Orange County to work for the Irvine Co. By 1965, executives at the foundation that ran the ranch were negotiating with the University of California, offering to donate land for a local campus with "shared green spaces."

They also promised to build a new town, which, said Watson, "turned out to be the city of Irvine."

From the beginning, said Watson, everyone involved with planning understood there would be a role for parks. But at first it wasn't clear how that would be accomplished.

With 93,000 acres — more area than the city of San Francisco — the Irvine Co. could afford to set aside sections for open space while other parts were developed, Watson said.

Company executives were aware of the "criticism North Orange County was getting" over the way it was developed, and "they didn't want that," said Watson. It fell to Watson, who had studied city planning triumphs like New York's Central Park, to devise a plan for using open space.

Working with architect William Pereira, the Irvine Co. adopted a plan that set standards for use of open space, including a mix of green belts and traditional parks, that have stood for nearly 50 years.

"There was no question in our minds; we were going to have parks," Watson said.

As other South County planned communities developed, parks were integrated into the initial plans. Rather than duplicate the urban grid of North County, roads followed the contours of the hills. Open spaces, trails and green belts were preserved.

"Those South County communities have stood the test of time and were remarkably well done," Daly said.

Please contact Tracy Wood directly at twood@voiceofoc.org and follow her on Twitter: twitter.com/tracyVOC. And add your voice with a letter to the editor.