Out of the darkness: Asian Americans confront the stigma of HIV/AIDS

In California, Los Angeles and San Francisco are among the 12 cities nationwide most affected by HIV/AIDS, according to the CDC. This project examines how Asians with HIV/AIDS are faring in these cities.

This piece is a component of a three-part series examining Asian Pacific Americans and HIV/AIDS healthcare in California.

Part 1. Out of the darkness: Asian Americans confront the stigma of HIV/AIDS

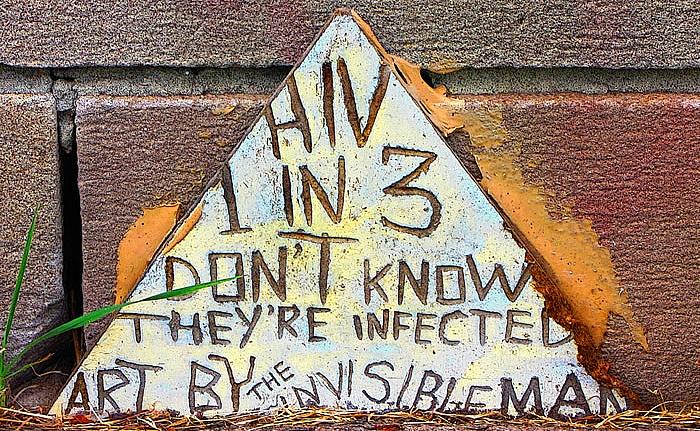

Part 2. Ending the silence: Asian Pacific Americans urged to increase HIV/AIDS testing

Part 3. HIV/AIDS Healthcare: The Ties that Bind and Divide the Asian Pacific American Community

A simple, strapless wedding dress is what Sara, 28, settled on for her summer wedding where she is expecting about 200 people.

Like most brides-to-be, Sara, who is part Asian American, is busying planning the minute details of her wedding from specialty cupcakes to the reception venue.

But unlike most who are soon-to-be wed, Sara has a secret she is keeping from some friends and family members. Sara, a heterosexual woman, is HIV positive.

“It was actually the only time I’ve slept with somebody without a condom,” said Sara, who requested to be identified only by her first name. “I think one of the things I did, is I kind of rationalized away the risks. I had one drink, but I was still pretty much sober and I was like, ‘Well, we’re both from Westernized countries, highly educated, in middle- to upper- socioeconomic status, so the likelihood is low.’”

The news of her HIV status was a devastating blow that left Sara in tears. Sara learned of her HIV status in 2006 after taking a sexually transmitted disease screening test.

She is one of the 4,053 Asian Pacific Americans (APA) who are living with HIV/AIDS in California.

When compared to other ethnic groups, APAs have the lowest percentage of cumulative HIV/AIDS cases, aside from American Indians and Alaskan Natives. Eighteen percent of the AIDS cumulative cases as of 2008 are Black, 54.9 percent are white and 23.8 percentage are Latino, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As of June 30 there were 5,771 reported HIV/AIDS cumulative cases in the APA community, according to the California Office of AIDS. APAs represent about 2.8 percent of the total cumulative cases.

But some HIV/AIDS healthcare workers say cultural values and pressures in the APA community often complicate dealing with highly stigmatized subjects like HIV/AIDS.

“The case is a little bit different when we’re looking at communities of color because HIV awareness is not as high, testing rates are lower, stigma is higher and the barriers to care are higher,” said Dr. Royce C. Lin, who works at the San Francisco General Hospital’s HIV/AIDS division. “As a result, as a public safety net hospital we see patients who come in when something bad has happened.”

Forty-year-old Henry, who agreed to speak only on the condition of partial anonymity, knows firsthand about dealing with the stigma of homosexuality and HIV.

At 23, after graduating from college, he was diagnosed with HIV. Despite practicing safe sex, Henry says he contracted the virus from his partner, who was open about his status. After contracting HIV, the Filipino American says he never thought he would live to his 25th birthday.

Henry’s parents’ negative reaction to his coming out as gay made him wait about five years to reveal his HIV status to them.

“This is what they pretty much told me, ‘our family’s well respected here. What would people think about us if they find out that you’re gay?’” Henry said. “And so if that was their reaction to me being gay, then what about with HIV? The stigma was even heavier in my mind.”

When Henry finally revealed his HIV status, his parents’ reaction to the news “pleasantly surprised” him.

As a gay male, Henry is part of the majority of those living with HIVAIDS in California. About 135,985 of the HIV/AIDS cases as of June 30 were men who have sex with men and bisexual men, according to the California Office of AIDS.

HIV healthcare workers, however, say they’ve learned to never make assumptions about which patients have the virus.

“Somebody may not have the ‘face of HIV’, so-and-so is not a gay man, so-and-so is not a drug user, so-and-so is not sexually promiscuous,” said Lin. “But that doesn’t mean that the person is immune or protected from HIV or couldn’t have HIV.”

Al and Jane Nakatani still remember how their youngest son Guy, who died of AIDS, was treated when he was hospitalized almost two decades ago.

“They had a big red ‘alto’ [stop] sign before you walked in, you had to gown up and wear gloves, and they served him on Styrofoam dishes,” Jane Nakatani said. “The nurse wouldn’t even want to take his temperature and said, ‘here you take it.’”

Guy’s ashes were buried alongside his two brothers at Maui Memorial Park. Al and Jane Nakatani used to visit their three sons weekly at the cemetery, two of whom died from AIDS and one from a shooting. Greg was the first to pass away in 1986 at the age of 23 after he was gunned down outside a Leucadia, Calif. taco shop following an argument over damage to his truck.

Glen, born in 1961, was the most private of the Nakatani children. At 15 he ran away from their home in San Jose, Calif. After being diagnosed with HIV, Glen returned home. He died in 1990.

“I had great dreams for all three of them,” said Jane Nakatani.

The Nakatanis say they will never forget the lessons they learned from the tragedy of losing all of their children. They continue to give educational and inspirational speeches nationwide through their nonprofit, Honor Thy Children.

“If we don’t step in to support, help and be understanding, then the kind of outcomes that took place in our family with Glen and with Guy will continue, and of course they do continue today,” said Al Nakatani about Glen and Guy, who identified as gay.

With President Barack Obama’s signing of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, many healthcare workers are speculating about the changes that will occur to HIV/AIDS healthcare in California from now until 2014.

“With healthcare reform hopefully more people will get [insurance], but I’m a little worried about the expertise being lost around HIV competency and really let’s face it in communities of color, HIV is still a highly stigmatized issue,” said Lina Sheth, director of community development and external affairs with the Asian & Pacific Islander Wellness Center.

Although, there has been progress made since the discovery of HIV in the 1980s, Sara says she thinks there’s still work to be done.

“I think that there are inroads in certain communities to be made,” Sara said. “I think that within the Asian and Pacific Islander community there’s still a lot of stigma.”

Certain family members and friends may never know of Sara’s HIV status because she fears being blamed, misunderstood or labeled as sexually promiscuous.

But her HIV status has not stopped Sara from looking optimistically at the future and discussing with her fiancé, who is HIV negative, the possibility of having children.

Being diagnosed with HIV has, Sara says, made her more determined to be a success in life.

“It’s not an immediate death sentence,” Sara said. “And you know my initial fear was, ‘I have 10 years, I’m going to live them as best as I can, and I want to make the most change I can.’ Now I have a much better outlook, thinking I could live into my 70s and 80s.”