‘Pandemic within a pandemic:’ What’s fueling LA County’s coronavirus death toll in nursing homes?

This story was produced as part of a larger project by Brenda Gazzar, a participant in the 2020 California Fellowship.

Her other stories include:

'This isn't a drill': How LA's Motion Picture home battled coronavirus

Known and loved: These six residents of LA’s Motion Picture home died of coronavirus

‘Behind the 8-ball:’ Many Southern California nursing homes hit hard by coronavirus had prior issues

A tale of two Southern California nursing homes in the era of coronavirus

Family of nursing home resident who died: ‘She had 3 really good years there and 1 really bad week’

Social isolation takes toll on Southern California nursing home residents during pandemic holidays

Can California nursing homes avoid the next ‘humanitarian crisis?’

This nursing home ‘angel’ struggled to support her family. Then she got coronavirus…

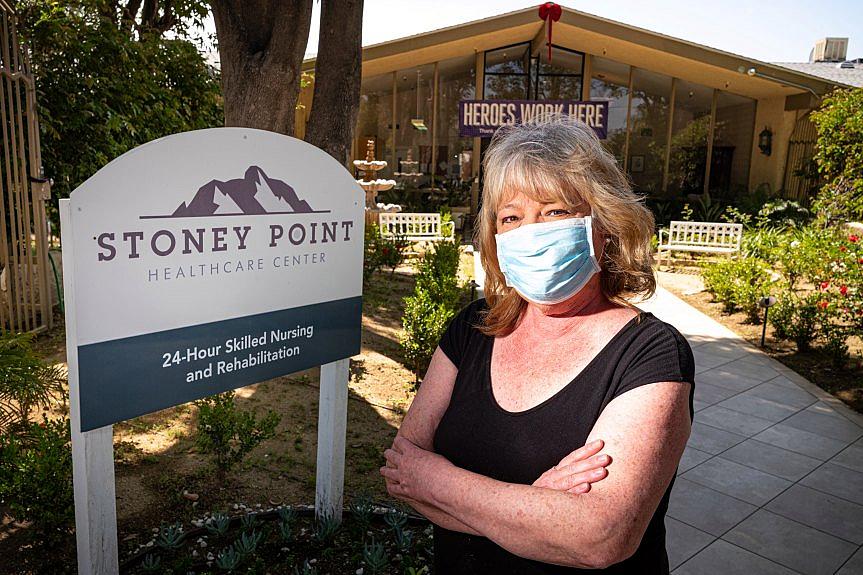

Lisa Cook at the Stoney Point Healthcare Center in Chatsworth, CA Wednesday, April 29, 2020. For several days Cook had no communication with her 62-year-old husband, a resident in Stoney Point nursing home in Chatsworth. When she finally convinced a nurse to let her FaceTime with her husband who recently had a stroke, she could barely recognize him.

(Photo by David Crane, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG)

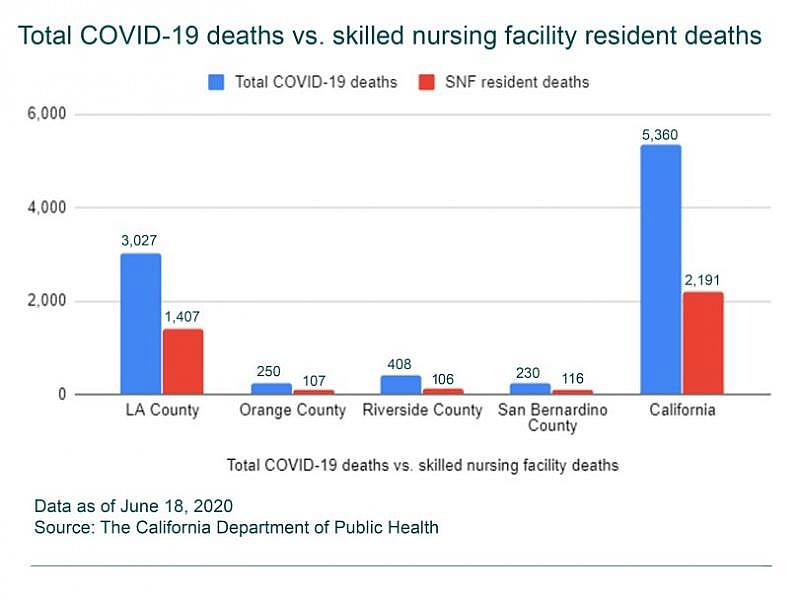

Despite comprising about a quarter of the state’s population, Los Angeles County makes up 64% of all the reported novel coronavirus deaths from skilled nursing residents in California and about 56% of the overall coronavirus-related deaths in the state, according to state data.

Residents in these facilities have proven especially vulnerable: About 46% of the county’s more than 3,000 COVID-19 deaths are from residents in skilled nursing homes, compared to 41% statewide.

But the figures based on Thursday’s data are likely off, partly because of under-reporting by facilities, and the data will shift for some time, experts said. Ultimately, nursing home deaths in the United States are expected to fall somewhere around 50% of the total coronavirus deaths, which is consistent with data from other nations.

Los Angeles County has become the state’s COVID-19 center. Local leaders have described the deadly toll within skilled nursing facilities as a “pandemic within a pandemic.”

It’s clear that the nursing facility residents are vulnerable to the virus because they are generally older, have disabilities or tend to have chronic health conditions. They also need intimate care such as bathing, feeding and grooming from a variety of caregivers, making physical distancing virtually impossible.

While L.A. County is not unique in having close to half of its total COVID-19 deaths from nursing home residents, certain traits may be helping to fuel the problem in the most populous county in the nation.

The county, for example, has some larger-sized nursing homes, which can contribute to outbreaks, said Jason Belden, disaster preparedness manager of the California Association of Health Facilities.

“If you have 600 staff members (entering a facility) versus 100 staff members, you have six times the risk,” he said.

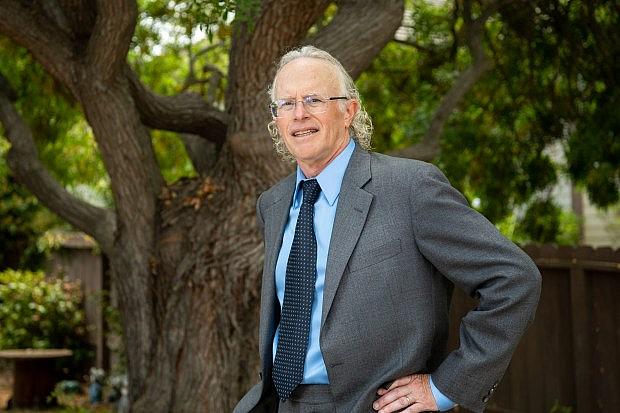

Large senior care facilities in urban areas also have been struck harder, said Dr. Michael Wasserman, a geriatrician and president of the California Association of Long Term Care Medicine.

“It’s very likely that coincides with a larger percentage of people of color,” who have been disproportionately affected by the virus, working and residing in these homes, Wasserman said.

Dr. Michael Wasserman is a geriatrician and president of the California Association of Long Term Care Medicine, Tuesday, June 16, 2020. He’s also medical director of Eisenberg Village in Reseda and has been a vocal critic of how Los Angeles County has handled the COVID-19 crisis in nursing homes. (Photo by Michael Owen Baker, contributing photographer)

Michael Connors of California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform argues the pandemic’s “horrific death toll” is because Los Angeles County has “some of the worst nursing homes in the nation” attributable to “dreadful oversight and unscrupulous operators.”

“Many if not most L.A. County nursing homes have long histories of understaffing and poor infection control practices,” Connors said.

A county inspector should be stationed at these facilities, particularly those with poor track records and outbreaks, every day to monitor care and “sound the alarm” if conditions worsen, he said.

Historically, the state has shared oversight responsibility with the county to inspect and enforce laws involving skilled nursing and other health care facilities, according to county officials. However, last year the California Department of Public Health transferred “full responsibility” of investigation and monitoring of these facilities to the county to improve enforcement.

“When you have these regime shifts, oftentimes, things take a while before they can essentially improve, and there’s a risk of things falling through the cracks in the handoff,” said Dr. Tony Iton of the California Endowment, a statewide health foundation. “The fundamental infection control practices at some of these institutions would go unkempt for a period of time.”

Citing the prevalence of patient dissatisfaction, low employee pay and poor quality of care, the L.A. County Board of Supervisors in late May approved the appointment of a watchdog to increase accountability and oversight in skilled nursing facilities. As of last year, the county had about 5,000 pending complaints related to nursing homes that required investigation.

“I think it’s critical we move quickly to prevent greater harm to our most vulnerable residents,” Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas said, introducing the motion.

To what extent issues such as infection control, staffing and quality ratings are playing a role in the COVID-19 crisis is under examination.

California nursing homes with one or more patients infected with coronavirus had generally worse quality on average, including in overall ratings and infection control, compared with those without cases, according to a Kaiser Health News analysis from May.

An early analysis by the Centers of Medicare & Medicaid Services of thousands of nursing homes across the country found facilities with a one-star quality rating on Medicare’s Nursing Home Compare “were more likely to have large numbers of COVID-19 cases” than those with a five-star rating.

Some preliminary research, however, indicates other factors may predict where the virus is likely to strike nursing homes and how hard.

Professor Vincent Mor of Brown University’s School of Public Health, co-author of an initial study examining about 3,300 nursing homes with COVID-19 in 10 states, said his team found nursing homes in counties with many confirmed cases were more likely to have a positive COVID-19 case, more cases and more fatalities. Larger facilities, which have more in-and-out traffic, also were more likely to have cases.

While infection control could be related to how rapidly the virus is spread or how much it can be controlled, Mor said, “we need a lot more close-knit data to be able to look at that.”

A poor quality nursing home in a part of the country that hasn’t seen much COVID-19 is unlikely to develop an outbreak, said Iton, a former director of Alameda County’s public health department. However, once the virus is circulating in a community, it’s logical that institutions with poor ratings or track records are more likely to suffer outbreaks.

“I don’t think that it’s rocket science that an institution that is chronically understaffed, has thin profit margins, has high turnover and doesn’t have good infection protocols or consistent infection control practices will be at a greater risk of any disease — and COVID-19 in particular because of its asymptomatic transmission,” Iton said.

Wasserman is confident that the virus will eventually strike every nursing home in the country. He also believes that preparation regarding infection prevention and control, staffing, resource allocation and leadership and management will make a difference in terms of the ultimate outcome.

“I’ve seen a lot of facilities flatten the curve in the facility, leading to fewer cases and leading to fewer deaths, and so there’s clearly a difference between facilities that get overwhelmed by the virus and those facilities that don’t,” he said.

Lack of early comprehensive testing in these facilities — along with inadequate amounts of personal protective equipment — has also contributed to deaths locally and around the country, experts said.

Los Angeles County public health officials had the ability to access a large number of tests by early April, Wasserman said. But they chose to make them available to the general public rather than to nursing homes.

“The general public is not who is dying,” said Wasserman, who is also medical director of the Eisenberg Village senior care home in Reseda. “It’s people living in nursing homes and assisted living (facilities) and the staff that lives there.”

The county was initially focused on “securing the community at home,” said Kathryn Barger, chair of the county Board of Supervisors. She said officials had also “underestimated” virus transmission from nursing home workers, some of whom hold two jobs.

“The more we researched the deaths, the more we saw they came from skilled nursing facilities,” Barger said. “When that became clear is when we recognized that we needed to triangulate and start doing testing at facilities.”

Flanked by Mayor Eric Garcetti and Los Angeles County Supervisor Hilda Solis, Supervisor Kathryn Barger speaks as public health officials and city and county leaders declare a local public health emergency as the number of coronavirus cases increase in Los Angeles County on Wednesday, March 4, 2020. (Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Pasadena Star-News/SCNG)

Barbara Ferrer, director of the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, acknowledged April 22 that her department had been wrong to focus testing around symptomatic patients, saying they now had a commitment to test all residents and staff in light of asymptomatic spread.

Two days later, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti ordered nursing homes in the city to offer monthly diagnostic testing for their staff and workers. The following week, the L.A. County Board of Supervisors approved a motion asking for a plan to improve the testing for coronavirus among residents within skilled nursing and other congregate living facilities.

Yet the slow pace of testing has frustrated families of nursing home residents, advocates and industry representatives alike.

Stoney Point Healthcare Center, a skilled nursing facility in Chatsworth, had its first confirmed COVID-19 case in early April, according to the facility.

However, baseline testing of all residents and staff wasn’t conducted until May 23, said Timothy Mason, administrator of Stoney Point, in an email. Surveillance or random sample testing also was conducted on June 8.

Nearly 30 staff and 32 residents at Stoney Point had tested positive as of Thursday, June 18, according to county records. Thirteen people have died.

When asked about the roughly six-week delay in testing, Mason said testing “occurs at the direction of county and state public health” officials. He said they followed their guidance.

County public health officials said they continue to help skilled nursing facilities complete COVID-19 testing but that “some facilities have made other arrangements to test their employees and residents on their own.”

The county’s public health department conducted “initial outreach” to Stoney Point on May 6, requesting information on all employees and residents so they can be registered with the lab for testing, according to the department. Nine days later, the facility provided that information. Baseline testing was completed eight days later.

Lisa Cook, whose husband Bruce resides at Stoney Point, said the county had been “so far behind” in taking care of widespread testing in nursing homes. As a result, she said, the facility became “a hotbed” for the virus.

She argued that Stoney Point’s administration also was “partly to blame” for not reacting sooner by testing all staff and residents on their own.

“I’m upset for the people that got sick and died,” she said, adding that the workers there have been “heroes” through this ordeal.

Lisa Cook at the Stoney Point Healthcare Center in Chatsworth visiting her husband. (Courtesy Lisa Cook)

Mason said that Stoney Point “has been vigilant and early for months in adopting the practices and protocols” from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services as well as the state and county “to protect the frail and vulnerable residents entrusted to its care.”

By late May, 163 skilled nursing facilities — or about 52% — of the 315 facilities under the purview of the public health department had tested all their staff and residents, Ferrer said. That excludes facilities in Long Beach and Pasadena, which have their own health departments.

She announced June 17 that the rest of these facilities had completed testing.

Testing is a collaboration between the county’s Department of Public Health, the county’s Department of Health Services, the city of Los Angeles and the facility, Ferrer said.

L.A. County officials have cited limited laboratory capacity, which has recently been bolstered by an outside lab, as a reason for the slow pace of testing. Ferrer also cited the complex mechanics of testing at these facilities, including some who need prodding or support.

“I know our team is working really hard — almost around the clock — to make sure we don’t continue to see delays, especially unnecessary delays in testing at skilled nursing facilities,” Ferrer told reporters on June 12.

The state recommended toward the end of May that all staff and residents of the more than 1,200 nursing homes in the state be tested for the virus.

Ferrer has noted a steady decline in daily average deaths in these facilities in recent weeks. She attributed that to the implementation of more infection control practices, including masking of everyone and more widespread testing.

When asked why the county didn’t require masks for all employees in the facilities until late April, the public health director said studies on asymptomatic spread in recent months have been “very mixed.”

“As soon as it became apparent to us in the nursing homes with data that actually demonstrated asymptomatic spread, we moved in very quickly to change our guidance,” Ferrer said, noting the county now has its “own data.”

Los Angeles County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer, at podium, speaks at a news conference with Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, left, in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes,File)

Many nursing homes are still in need of N95 masks and isolation gowns, said Belden of the California Association of Health Facilities.

“Abundant personal protective equipment is critical in order to battle COVID-19,” Wasserman wrote in an email to a county public health official on April 16. “We cannot depend on facilities to provide this.”

Ferrer told reporters the county is ensuring “nobody runs out of” personal protective equipment in skilled nursing facilities but “could do better, I think, as a whole” with state and federal agencies to ensure nursing homes have an “adequate stockpile.”

Meanwhile, observers note that many nursing home deaths could have been prevented with quicker action around the state.

Dr. Noah Marco, chief medical officer of the Los Angeles Jewish Home, said his facility shared half of its first 500 test kits received from the city of Los Angeles with Brier Oak on Sunset. This is how that skilled nursing facility, he said in an email, “discovered the extent of the virus in their building and controlled their outbreak.”

Marco and colleague Wasserman urged county health officials by email in April to send test kits to the Los Angeles Jewish Home so that they could then distribute them to nursing homes throughout the county. They said they got no response.

“If nursing homes were provided testing kits earlier in the pandemic, it would have saved lives of several of the residents and the staff that died,” Marco said.

Brenda Gazzar wrote this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism‘s California Fellowship.

[This article was originally published by Los Angeles Daily News]