Part 1: Black babies die at twice the rate of white babies. My family is part of this statistic

This project received support from the Center for Health Journalism's California Fellowship and its Fund for Journalism on Child Well-being.

Other stories in this series include:

Why are black babies twice as likely to die as white babies in the US?

America's black babies are paying for society's ills. What will we do to fix it?

Saving black babies by saving a whole neighborhood

What's behind the high black infant mortality rates? Racism, not race

Empowering moms – and dads – in the black infant mortality crisis

Moving from talk to action on black infant mortality plan

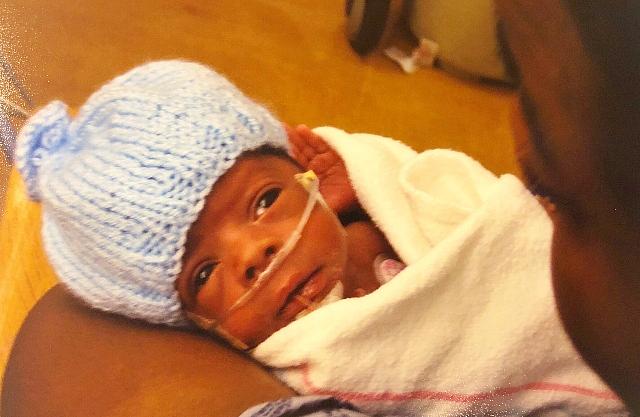

Priska holding her nephew Isaiah, who was born premature. He is now a happy, healthy 11-year-old (Photo courtesy of the Neely Family)

She didn’t cry like I thought she would. I’d asked my sister Nicole to talk about the babies she lost nearly 20 years ago.

She only made it to four months when her body started to go into labor the first time.

“I think I remember hearing [him make] a sound,” she said, “but he was so small.”

He didn’t make it.

She made it to five months the second time. “He lived for a week, which actually is kind of worse than the other one,” she said. “Because you have more attachment. You think he's going to be okay.”

Here’s what you need to know about my sister: she cries all the time.

She cries out of pride when she hears me, her baby sister, on the radio. She cries from the rollercoaster of emotions triggered while watching “Chopped” or “The Voice.”

But she didn’t shed a tear when I told her the heartbreak she’d suffered was part of a national narrative that has hurt black families in America for decades.

“I don't really talk about it at all, ever,” she said.

I told her that black babies in the United States are two times more likely to die before their first birthday than white babies.

I told her that most of the babies die because they are born too early and too small.

I told her that a black woman with a college degree, is more likely to lose a baby than a white woman with no high school diploma.

“Whoa!” she said. “That's crazy.”

I told her that the research has evolved over the years from blaming mothers, to questioning whether genetics explained the gap, to where it is now: that the cause is a social one, and the suspected assailant is chronic stress brought on by being a black woman in this country.

Poverty, education, prenatal behavior, and access to health care all contribute to the issue - but none of those factors explain the gap in birth outcomes that has persisted for decades.

In addressing the gap, the field is now focused on the social determinants of health - the structural and institutional racism that manifests itself in the health care system, in social and physical environments, in access to education and treatment in the workplace.

Hearing this did make her sad, but she didn’t cry. Like so many other black women who are part of this statistic, she had no idea of the scope of the issue.

“Now that I know that this is an issue, and I was part of a statistic in this sense,” she said, “if I can help someone and prevent that, then I am more than happy to share my story.”

“I'm just thinking that it's just me, and it is — it was my body — but the care that I was given in that process could have, maybe if it was in a different situation, it would have been a different outcome. I'm just not sure that we're aware that this is an issue beyond just our bodies.”

Most people are not aware.

When I found out about this alarming statistic last year, it hit me hard. I was at a conference on maternal health and was drawn to a session about trauma and birth outcomes for black women.

I was in a room with other black women — some health advocates, some medical professionals.

Many of us were learning about the unusually high mortality rate for black babies for the first time. Some of the women, like my sister, had their own stories. They raised their hands and shared how they’d personally lost infants or given birth prematurely. They, too, did not realize they were part of the statistic.

In the room that day, I immediately thought of the experiences of not just my sister Nicole but also my sister LaKisha.

Isaiah and LaKisha (Photo: the Neely Family)

LaKisha, a married woman with a master’s degree, developed preeclampsia with her first pregnancy. The complication, which includes high blood pressure, is one of the leading triggers of premature births — and it affects black women at a higher rate and is linked to the equally alarming rates of maternal death. My nephew Isaiah, was born two months early, weighed just two and a half pounds.

Isaiah, now 11, is healthy and thriving in school. I recorded him talking about what he knows about being a preemie, and I cry nearly every time I listen to it.

“Well, I remember that I was - I don’t know, I could fit in my mom or my dad’s hand,” he said.

I cut in, asking if he possibly had an actual memory of that.

“No, but I know that!” he retorted.

He’s seen the pictures of himself with the breathing and feeding tubes taped to his skin in the neonatal intensive care unit incubator that he called home for six weeks.

When he was born, Isaiah spent six weeks in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. (Photo courtesy of the Neely Family)

Since learning about these statistics and how my family fits into the broader story, I’ve been asking myself these questions on repeat:

How has this been going on for so long? And, if the problem is societal, what are we, as a society, going to do about it?

Now I’m trying to answer them.

For months I’ve been talking to researchers, community health workers, educators and others who are working to improve birth outcomes. I begin most of my interviews by asking how they found out about the disparity in infant mortality rates. Some happened upon the information while searching for research topics in grad school. Others learned once they experienced their own loss.

I’ve also learned that this is not an issue that can simply be solved in a hospital or clinic. This problem is big and persistent and complex. Like most health inequities, this is about social and economic systems and the distribution of money and power.

The infant mortality rate for black babies is just one data point in the story of inequality in the United States.

“It has been centuries in the making,” Tyan Parker-Dominguez, a leading researcher on infant mortality disparities at the University of Southern California, told me. “So it's not something that's going to be undone overnight.”

Over the next few weeks, I’ll be sharing stories of people in Southern California and across the country who are trying, in ways big and small, to change the statistic.

In Los Angeles County, public health officials are launching a new plan to close the gap, with a fight against racism at the core of the initiative.

In Oakland, I met people who are working to save black babies by improving the health and well-being of everyone in the neighborhood - but that's slow going.

In Ohio, which has one of the highest infant mortality rates in the country, I spent time with community organizers who are starting with small, tangible steps - by educating black men about the issue and teaching them about putting babies to sleep safely.

One major takeaway is that there is not enough awareness about this problem - among black women, within the medical field, within public health and the general population. The well-being of babies is something that affects us all.

If you’ve had experience with this issue and want to share your story with me, here’s how to get in touch. I'll read every submission, but nothing is shared without your permission.

A version of this story was also on the radio. Listen to it here.

[This story was originally published by laist.]