Part 1: Burmese American Community's Vaccination Efforts

This story was written by SweSwe Aye while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2021 California Fellowship.

Part 2: Health and mortality impacts on Burmese Community by COVID-19 pandemic

Myanmar Gazette

Part 1 - Community efforts for vaccination

"Dynasty Theater," was a popular gathering place for the Burmese community, until it was closed because of the pandemic. But every Saturday since April, once again, the simple white one-story building, just the exit of 10 Freeway at Baldwin Place, El Monte, has a long line of people outside- a sign of its transformation from a community performing arts center to a vaccine site for the Burmese community in Los Angeles.

There are many vaccination centers in Los Angeles, but for the Burmese, this is possibly the most important one. Many of the Burmese community are settled in nearby Orange County and San Gabriel valley, so it’s centrally located. This building has also been a neutral gathering space for the incredibly diverse Burmese immigrant community, which has 135 recognized ethnic groups and more than 100 different languages. But perhaps most importantly, Dynasty Theater holds positive memories for people standing in line for the vaccine. “We celebrate our community events here regardless of religion. It is one of the vital organs of our community,” said Soe, a Burmese web developer, who asked that we not use his last name.

David Chan, one of the organizers of this vaccine program, who is also the supervisor of Dynasty Theater, is hoping that that trust and connection helps encourage more Burmese to get vaccinated. The numbers are encouraging. In the first week, 750 people got vaccinated, with 600 more coming through in the first month. “We’re very happy with these numbers but we’re hoping for even more people,” Chan said.

About 80 percent of those getting vaccinated at this center are Burmese. Many of whom are grateful for the vaccine. Htae, a 64 year old who asked that we not use her last name, is a cancer survivor. “We are blessed to still be alive today, and now I am protected because of the vaccine,” she said. Two high school students were also in line wanting to get vaccinated. “We are more than happy to go get vaccinated if that means we can go back to school and be with our friends,” they said. Many asked if they could buy the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine for their close relatives in Burma so they could be protected as well.

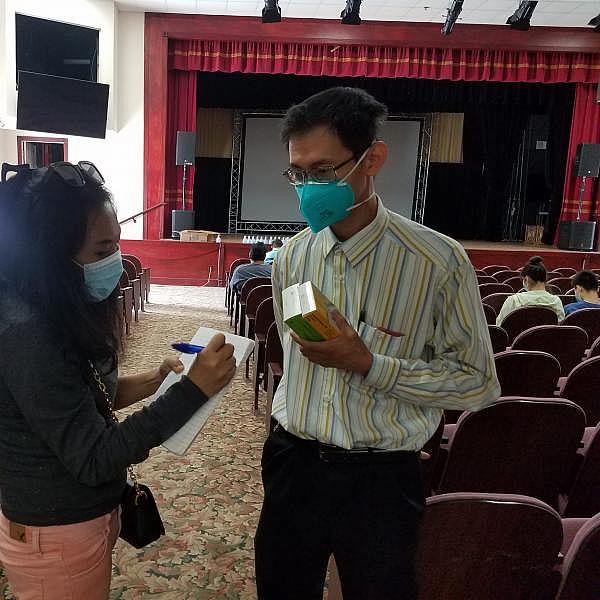

But there are still some in the Burmese community who are hesitant to get vaccinated. Many don’t speak English. According to a 2019 Pew Research Center study, just 38% of the Burmese population in the U.S. is proficient in English. Some don’t have internet access, so they couldn’t sign up for vaccine appointments and seniors, especially, have poor digital literacy. And there is a lot of misinformation about the effectiveness of vaccines. “Some people don’t believe Covid-19 is real. They underestimate the virus as seasonal flu and don’t realize the consequences of getting infected,” said Dr. Than Saung Lin, a Burmese doctor who is volunteering at the Dynasty Theater vaccination program. “Others don’t trust the vaccine. We need to give out accurate information about the virus and the vaccine so more people in our community get vaccinated,” he said.

Some in the Burmese community want to get the vaccine but have other concerns. One 56 year old woman said she wanted to get the vaccine for herself and her two daughters, but held off because they were uninsured and believed she couldn’t afford it, not realizing all vaccinations are free across the country. She is also undocumented and expressed fears based on misinformation about a now cancelled Trump-era policy that would reject legalizing immigrants if they could not afford certain social and health services. That policy was cancelled and Covid-19 treatment was exempted.

David Chan, one of the organizers of the vaccine program, has tried to reach out to Burmese who are hesitant to get the vaccine through emails, social media posts and advertisements in the community newspaper. They also asked 12 trusted Burmese organizations such as the Burmese American Medical Association, the Burmese American Science and Engineering Organization and the Burmese Welfare Organization, to reach out to their members and urge them to get vaccinated as well.

The irony is that while some in the Burmese community living in the U.S. are hesitant about getting the Covid-19 vaccine, wealthy residents from Burma have flown to the U.S. just to be able to get the coveted Pfizer or Moderna shots. Like Aye, a 63 year old retired professor, who asked that we not use her last name, hasn’t returned to the U.S. for five years but says the vaccine gave her a very good reason to do so. She believes that the Pfizer vaccine was more effective.

Even though there is a lot of hesitancy, public health directives have forced some in the Burmese community to receive the vaccine. U Kyi's two daughters are attending U.S. universities which have mandated that students and their visitors be vaccinated. So reluctantly he and his wife got the shots. "At first I was frightened to get vaccinated but we haven't had any big problem after getting vaccinated. Except for a sore spot at the injection site for a day!" he said.

In August, the vaccinate program at Dynasty Theater also expanded to give out booster shots to immunocompromised residents. And David Chan says the vaccination team will continue to urge residents to get vaccinated. “We tell them that this is not about vaccinating individuals, this is about protecting our community,” he said.

SweSwe Aye wrote this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism‘s 2021 California Fellowship.

Swe Swe Aye received training, financial support and reporting and engagement mentoring for this project as a USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2021 California Fellow.

[This article was originally published by Myanmar Gazette. Click here to view the original.]