This Paterson school struggles with high absenteeism, poverty — and potential gang threat

The story was originally published by the NorthJersey.com with support from our 2024 Data Fellowship.

Public School No. Six in Paterson, NJ is shown on Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025.

Anne-Marie Caruso/NorthJersey.com

It was just another recent frigid winter afternoon, but for Paterson native Yazmin Robinson, it marked a personal milestone. Her 5-year-old had finished her first day of kindergarten at Paterson’s School 6, and it was a moment to cherish for Robinson, 30, who had left high school in her teens to help her family pay the bills — and who later missed the chance to send her daughter to preschool because they were temporarily homeless.

Robinson and her daughter had, at least for the moment, overcome the hurdles that cause many children in New Jersey's school districts to miss school far too frequently.

While urban and even suburban school districts across New Jersey continue to grapple with a major, disturbing fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic — high rates of chronic absenteeism — Paterson's School 6 in particular faces a barrage of hurdles that has exacerbated its absenteeism problem.

School 6, a K-8 school in the city's poverty- and crime-prone 4th Ward, saw chronic absenteeism at a staggering 48.4% in 2020-21 as the school returned to in-person learning amid the pandemic. But then, even as the pandemic eased, chronic absenteeism climbed to 59.1% in 2021-22, and to 60.7% in 2022-23.

In the past two school years the absenteeism rate has finally started to decline, but it remains elevated at 27.5%, the district said. And that's an alarming problem. Chronic absenteeism is linked to a higher chance of dropping out, which can lead to weaker job prospects, poor overall health and a higher risk of involvement in the criminal justice system, experts say.

Poverty, transience, homelessness, illness and transportation issues are among the many obstacles facing Paterson's school-age children, and none more so than those in the 4th Ward neighborhood served by School 6.

"We have pockets where there is high need," said Laurie Newell, Paterson's schools superintendent. "There is higher blight in some spaces," she said, referring to the 4th Ward. "In these areas our kids need layers of support." And now, on top of everything else, School 6 appears to be facing yet another new problem: a juvenile gang, county probation and city police officials have reported.

The story of School 6 is about a community raising its children in an area that has battled extreme poverty, broken homes, homelessness and drug activity for decades. Only if the school, businesses, stakeholders and parents whose kids struggle the most join forces will they be able to tackle some of the many challenges that exacerbate high absenteeism, advocates say.

School 6 serves one of the poorest parts of Paterson

School 6 is in a section of Paterson’s 4th Ward that has still not recovered from the long-term effects of the crack epidemic of the 1980s, said Ernest Rucker, 71, who attended the school as a child growing up in Paterson. He now runs the Grandparents Resource Center and Save the Village, nonprofits aimed at helping inner-city kids.

"I think not enough attention is being paid to not just the kids but the whole family dynamic in the School 6 area,” Rucker said.

He works to support grandparents like himself raising their grandchildren in Paterson in a school zone other than School 6.

The median age of adults living near the school is 24 to 26, with a per capita income of about $18,000. Families run by single women outnumber two-parent households, according to census tract data.

Officer in Charge Isa Abbassi, of Paterson Police Department, talks with Ernest Rucker, community activist, while visiting local businesses in Paterson on Tuesday, Oct. 8, 2024.

Julian Leshay Guadalupe/NorthJersey.com

A park with shiny red slides behind the school has a tall chain-link fence around it. A 4th Ward redevelopment plan in 2017 suggested reducing the large number of vacant, dilapidated buildings and chain-link fences to revitalize the area.

“A lot of these parents are young themselves, from broken homes," Rucker said. "There’s a lot to that family dynamic that has not really been studied by the school district."

Inner-city kids and their parents need different solutions from suburban families, he said: “I believe that we have never come out of that one-box mentality. It's a different child in the inner city, a different mindset, a different culture. It's so many different variables that we must start thinking differently to achieve the same goals.”

Today's parents with school-age kids had difficult school experiences

Yazmin Robinson picked up her 5-year-old daughter from School 6 on that recent, promising first day of kindergarten as children tumbled out of the front door. Robinson rents an apartment with assistance from the state after being homeless in 2023, she said.

Her daughter missed a year and a half of state-funded free preschool while they were homeless, Robinson said. She does not have health insurance, so School 6's full-service community program stepped in to provide her daughter, who has food allergies, with an EpiPen and Benadryl to attend kindergarten safely. The paperwork delayed her start in public school.

Yazmin Robinson, who has a child in preschool at Public School No. Six, poses for a photo in Paterson, NJ on Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025.

Anne-Marie Caruso/NorthJersey.com

Robinson's own school experience was not optimal, and it provides an example of the sort of generational challenges some of today's young parents had with school. She had to leave Paterson's John F. Kennedy High School before graduating to help put food on the table for herself and her elementary-age siblings, she said.

"Early, I had to choose between school and being financially stable for myself to survive every day," Robinson said. "As the oldest child, I felt it was way more important for my mom to provide for them first." Robinson signed a contract promising to be in school when she realized her "attendance was horrible."

Then, in ninth grade, she learned she could sign herself out of school, and stopped attending completely. She began taking a bus to Paramus to work at Wendy's.

At 21, Robinson, who dreams of making it as a dancer, enrolled in a 10-month program offered by the New Jersey Community Development Corporation for older youths who want to earn a GED. She left the program because the $200 weekly check she said it provided wasn't enough to help support her now-grown siblings.

She now takes high school classes offered by the state, she said, and "is one test away" from a high school diploma.

“It’s rough out here" around School 6, she said. "It’s bittersweet, because I love the 4th Ward. I have family and community here. You can’t deny the reality around here. You do feel sorry for the children who witness some of what goes on."

High chronic absenteeism after COVID pandemic

In 2012, School 6 was among six district schools placed under review by the state. An assessment team delivered a stinging criticism of the school's culture and staff at the time. It stayed open, changing principals a few times.

In 2018, the district hired part-time specialists to tackle engagement and attendance issues. Then came the COVID-19 pandemic, when the numbers of chronically absent students — kids who miss school at least two days a month — hit an all-time high, both nationwide and particularly in urban districts.

In 2023 and 2024, School 6 had the highest chronic absenteeism rates compared with other public K-8 schools in Paterson, according to data from the district obtained by NorthJersey.com through a public records request.

Public School No. Six in Paterson, NJ, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025.

Anne-Marie Caruso/NorthJersey.com

New Jersey school districts are expected to create annual corrective action plans to address chronic absenteeism if rates go above 10%, according to state regulations. A student is chronically absent if they miss more than two days a month or 18 days in the 180-day school year — including excused absences.

The district says it actively uses compulsory attendance specialists to follow up with students and address attendance concerns. Paterson stopped using badge-carrying truancy officers years ago.

For two years now, the state has flagged School 6 for being in the bottom 5% of Title I schools that receive federal funds for low-income students. In 2022 and 2023, School 6 was also identified as needing Comprehensive Support and Improvement, based on eight federal criteria, of which a chronic absenteeism rate is one.

Challenges of generational poverty, family dynamics

Some longtime Paterson residents and community advocates said generational poverty, the breakdown of family and disengagement among a mostly young population of parents whose children attend School 6 are stubborn problems that the school district cannot fix alone.

Solutions could lie with a mega-donor who has a vision, or if the city works more closely with the schools, they say.

Two other elementary schools, School 13 and School 10, are equidistant from School 6, each just under a mile away. Both struggle with similarly high rates of chronic absenteeism and low academic performance, but School 6 scored lowest on a calculation based on a federal performance rule.

"There are specific challenges in the neighborhood surrounding School 6", said Rosie Grant, who heads the Paterson Education Fund, a non-profit that works with the schools.

Danielle Parhizkaran/NorthJersey.com

In 2014, School 6 became a Full Service Community School, one of many in Paterson that receive federal funds to help the school community thrive with “wrap-around supports” that link it with outside partners, including health services.

"There are specific challenges in the neighborhood surrounding School 6," said Rosie Grant, who heads the Paterson Education Fund, a nonprofit that works with the schools.

It isn't realistic to expect the school to fix the community, she said. "City departments, the county, the nonprofit community, businesses are all stakeholders. We need them to come together and begin saying, 'Here's what I have to offer.'"

In November 2023, Paterson was the only New Jersey district to win a $2 million grant from the Biden administration to expand its full-service community schools.

Added challenge of a possible youth gang

A gang with children as young as 12 and 13 attending School 6, also known as Senator Frank Lautenberg Elementary School, is allegedly operating in the neighborhood on Rosa Parks Boulevard and Montgomery Street, said an email sent by an officer in Passaic County Probation Services to alert colleagues. Probation Services is a court program designed to keep youths out of jail while under state supervision.

However, an alleged “ringleader” attends Norman S. Weir School, another K-8 school in Paterson, the email said, and the children could have access to weapons such as handguns.

A photo circulated with the email, taken at night, shows a group of small boys standing close together on a bench in a park and making distinct hand gestures.

The Paterson Police Department confirmed the existence of the gang, which allegedly goes by the name "YBC."

"YBC is a gang Paterson Police Department is monitoring and investigating," a spokesperson said. "They trend younger than other juvenile gangs.”

Rucker, who is also on the Paterson Police Department's advisory council, created after the state takeover of the department, said he has been aware of intelligence about the YBC gang for about four months.

The school district said it had no information about a gang operating around School 6 and said it could not comment on the police investigation because of “reasons related to security and the privacy of minors.” YBC stands for Young Bag Chasers, said law enforcement sources who did not want to be identified. The "bag" reference is likely to be moneybags but could also mean drug bags they sell, sources said. “Chasing bags” is also street slang for making money and is not always used with a negative connotation.

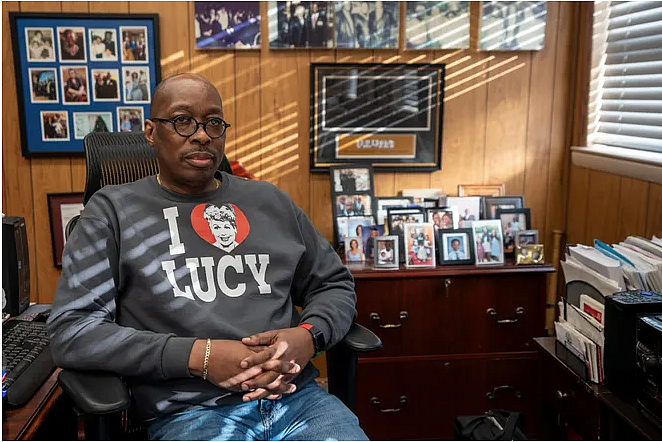

The Rev. Kenneth Clayton poses for a photo in his office at St. Luke Baptist Church in Paterson on Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2205.

Anne-Marie Caruso/NorthJersey.com

It is not uncommon for inner city gangs to recruit younger members, but references to juvenile gangs can be conflated with “street crews” — groups that kids form on their own and without any connection to organized gangs. Police are not sure which category fits YBC.

The Rev. Kenneth Clayton, a Paterson native and pastor at St. Luke’s Baptist Church, right across the street from School 6, said he was not surprised to hear that there might be a youth gang active in the neighborhood. He has worked at the church for 28 years. “In an urban community like ours, I’m sure there’s gang activity,” he said. “The parental piece” is missing in the School 6 area, he added.

With enough resources, he would start a parent mentorship program to provide younger families one-on-one support. Clayton wants to begin by connecting mentors with two or three families in School 6 and grow the effort — a plan he devised before the pandemic that never took off.

“People have to be committed to helping parents for the long haul,” he said. “The village has to be healthy and responsible. We need a village, not just a school.”

Though Clayton said he was not surprised to hear there could be gang activity in the neighborhood, he and Zellie Imani, a Black Lives Matter activist who works with school-age children, said they had never heard of a gang linked directly to the K-8 school.

A neighborhood with difficult odds

Both agreed that the school’s immediate neighborhood — which has seen gangs and drug and prostitution rings — has created a setting where children face very difficult odds.

Imani pointed out there is a “food desert” around School 6, a term for urban areas where it is difficult to buy affordable, high-quality fresh food. There’s also a lack of recreation opportunities in the neighborhood, Imani said. All of that combined makes it difficult for students to thrive.

Public School No. Six in Paterson, NJ is shown on Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025.

Anne-Marie Caruso/NorthJersey.com

"Guns and gang violence are also common in that area — the children are dealing with things that can’t be fixed by a 20-minute social emotional learning period in school,” Imani said.

A community school is meaningless "without true community involvement,” Rucker said. That could mean temporary but stricter measures to engage parents. “How would you make something as simple as attending a parent-teacher meeting an enforceable requirement?” he said.

He also said a community school must listen to what the community needs. “You bring in your stakeholders first, your local ministry, your local community leaders, your advisers, and the children. And you have a certain conversation there,” Rucker said.

Middle school children a target for gangs

Middle school children are an attractive target for inner-city gangs because they typically face less harsh penalties and lesser sentencing guidelines than older youths and adults for similar crimes.

“While recruiting juveniles for gang affiliation is nothing new, it does appear the gangs are targeting juveniles at a much younger age,” the email circulating through the courts said.

School 6, also called Senator Frank Lautenberg Elementary, is in the fourth ward and in one of the poorest sections of Paterson.

Mary Ann Koruth

Clayton’s church provides summer and after-school programming, as well as direct support to families. “I try to steer them toward responsibility and engagement," he said. "But families need to show up. I can only work with people who are willing to work with me.”

“Whatever the deterioration of a community, whatever those realities are, none of those things determine that a child cannot make it," Clayton said. "If you believe in yourself and your child, you can push your child forward beyond those limitations.”

The problem is a lack of hope, which leads to lack of motivation, he said.

“What gangs do with a child, particularly, is they create a family dynamic for that child," Clayton said. "If you have a family that you’re connected to, you don’t need a gang. It goes back to the family. We have to find a way to heal.”

Joe Malinconico of Paterson Press contributed to this story.