Patterns of death in the South still show the outlines of slavery

Reporting for this story was supported by the Center for Health Journalism’s Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism and the Fund for Journalism on Child Well-being.

(Photographs by Johnathon Kelso/FiveThirtyEight)

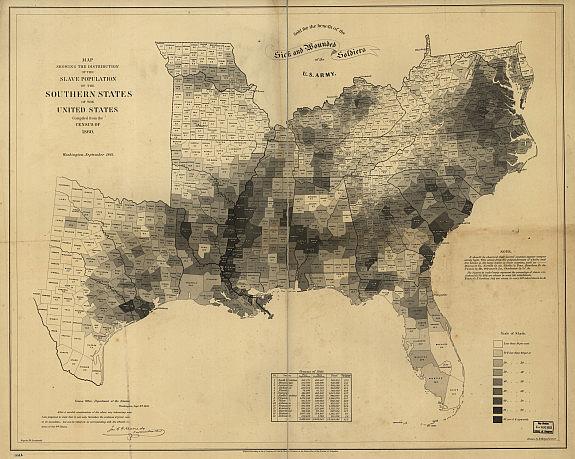

There’s a map, made more than 150 years ago using 1860 census data, that pops up periodically on the internet. On two yellowed, taped-together sheets of paper, the counties of the Southern U.S. are shaded to reflect the percentage of inhabitants who were enslaved at the time. Bolivar County, Mississippi, is nearly black on the map, with 86.7 printed on it. Greene County, Alabama: 76.5. Burke, Georgia: 70.6. The map is one of the first attempts to translate U.S. census data into cartographic form and is one of several maps of the era that tried to make sense of the deep divisions between North and South, slave states and free.The map, which depicts census data, had political motivations, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. It was drawn by pro-Union government officials who wanted to create a visual link between secession and slavery.

">1But the reason the map resurfaces so frequently is not just its historical relevance. Rather, it’s because the shading so closely matches visualizations of many modern-day data sets. There is the stream of blue voters in counties on solidly red land in the 2016 presidential election, or differences in television viewing patterns. There’s research on the profound lack of economic mobility in some places, and on life expectancy at birth.

Ana Arana is an award-winning investigative journalist and former foreign correspondent who reported for three decades in Latin America and Africa. She has received multiple journalism awards, including a Peabody Award, two Overseas Press Club Awards, and a Dart Award for Excellence, among others.

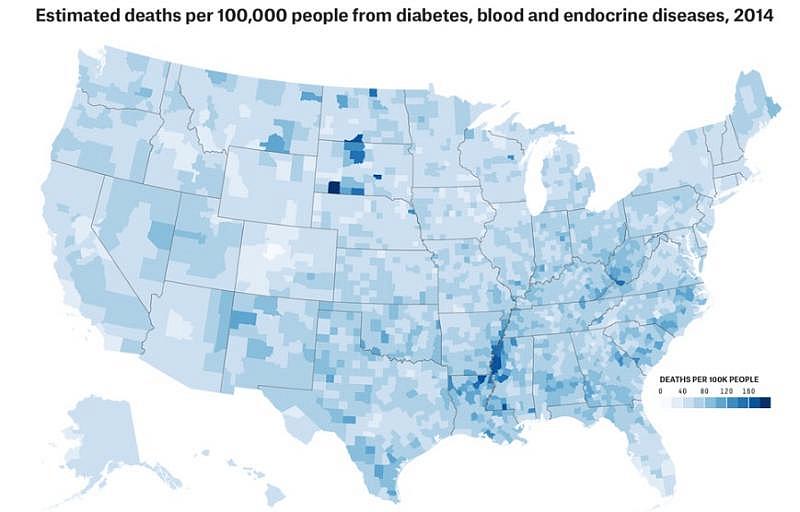

On major health metrics in the U.S., the shaded counties on the antebellum map still stand out today. Maps of the modern plagues of health disparities — rural hospital closings, medical provider shortages, poor education outcomes, poverty and mortality — all glow along this Southern corridor. (There are other hot spots, as well, most notably several Native American reservations.Despite a scarcity of data, Native American health disparities are well documented, as are rampant poverty, unemployment and low educational attainment. According to the Indian Health Service, the life expectancies for Native Americans are 4.4 years shorter than those of the U.S. population as a whole.

">2) The region, known as the Black Belt, also features clearly on a new interactive created by FiveThirtyEight using mortality projections from researchers at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington. The projections show that, while mortality is declining nationally, including among those who live in the Black Belt, large disparities in outcomes still exist. Over the next several weeks, we’ll be looking at some of the causes of these disparities in the Black Belt and talking to the communities they affect.Though these health outcomes are associated with race, race is not the cause of disease. “There are certain genetic factors, of course,” said Ali Mokdad, one of the IHME researchers, who previously oversaw one of the largest public health surveys in the U.S. “But … we like to say, ‘Diseases don’t know race.’” Instead, Mokdad said things such as racism, economic deprivation and poor education — measures that together are part of what is called socioeconomic status — are largely to blame.

The Black Belt was the origin and center of not only Black America, but also of rural Black America. Today, more than 80 percent of rural black Americans live in the states that form the Black Belt. Black men in the region routinely have mortality rates 50 percent higher than the national average.

In 1860, when 76.5 percent of the people in Greene County were enslaved, the entire population totaled more than 30,000. Today, the county has less than a third the number of people it did back then, but blacks still constitute more than 80 percent.

The Rev. Christopher Spencer is tall and thickly built with a bald head and narrow-rimmed glasses. His presence is large, but never more so than when he’s swaying in church robes, preaching on a Sunday morning. His church, St. Matthew Watson Missionary Baptist, is tucked away in a clearing in the woods of Greene County, just off a country stretch of U.S. Highway 43 and about 30 miles from where he grew up.

The church, which recently celebrated its centennial, still has about 130 members despite the shrinking of the area’s population. Preaching is Spencer’s passion, but he also works as a director of community development at the University of Alabama, helping recruit people for studies and pushing for jobs and opportunities in the Black Belt.

The Black Belt moniker first referenced the rich, fertile soil that millions of African slaves were forced to work, their labor making the European settlers some of the wealthiest people in the world. By the turn of the 20th century, the name had come to identify rural counties with a high percentage of African-American residents. “The term seems to be used wholly in a political sense. That is, to designate counties where the black people outnumber the white,” wrote Booker T. Washington in his 1901 book, “Up From Slavery: An Autobiography.”

The Black Belt is filled with complicated realities. It was the center of the civil rights movement but still has some of the most consistently segregated schools in the country. White Europeans wanting to reap from its verdant soil forced millions of slaves to the area, but today healthy food is hard to find. Deeply rooted social networks tie people to the land and community, but poverty and racism led millions to leave the area in one of the largest internal migrations in human history.

Fields near Eutaw, Alabama, in 2016 and 1936. Johnathon Kelso; Library of Congress

Reporters often illuminate the problems of the U.S. health care system by looking to outliers, the least healthy places, such as the state of Mississippi or a parish in Louisiana. That makes sense; states and local governments are largely responsible for the education, insurance, hospitals and economics that drive health outcomes. But in the case of the Black Belt, those borders obscure the broader pattern: rural, Southern black Americans who live in communities founded on slavery routinely have some of the worst health outcomes in the country.

Some recent media coverage has focused on a disturbing rise in mortality among U.S. whites with a high-school education. A much-publicized series of papers by Anne Case and Angus Deaton showed that mortality for whites with a high school education or less is increasing and included a chart showing that it is now greater than mortality for blacks. The rise in mortality made headlines and is a concerning trend worthy of study, but the headlines obscured several important facts, chief among them that the chart showed mortality for all U.S. blacks, not only those who also have a high school education or less. After the authors were criticized for leaving blacks off a different chart in one of the papers, they told The Washington Post “the reason it’s not there — which we explain — is that black mortality is so high it doesn’t fit on the graph.”

In other words, the trends — an increase in mortality for some whites, a decrease for most blacks — are important, but so are the absolute differences, and blacks continue to die younger than people in other groups.

Greene County, home to St. Matthew, is fairly typical in Alabama’s Black Belt: 55 percent of children live in poverty, and the unemployment rate is 10.6 percent, more than double the national rate. There are primary care physicians in Eutaw but residents say they must travel to distant Tuscaloosa for most specialty care.

Calvin Knott drives the 12 miles from his home in Forkland, in the southern part of the county, to attend church at St. Matthew. After decades working at the area’s power company, he’s spending his retirement driving a bus that takes people to and from medical appointments in Birmingham and Tuscaloosa. Most of the passengers are on Medicaid, he said. The insurance program for low-income people will pay the cost of transportation to some appointments, but Knott said he knows a lot of other people without insurance who just don’t go to the doctor.

Under the Affordable Care Act, states can expand their Medicaid programs to include everyone earning less than 138 percent of the federal poverty level, but only two of the states that form the Black Belt, Louisiana and Arkansas, chose to do so. Knott finds that disappointing. “It wouldn’t benefit me, but I’d be happy for my taxes to go to helping other people,” Knott said.

Churches in rural Alabama, undated (left) and in 2016. Library of Congress; Johnathan Kelso

Experts say a long history of racism and poverty has left the region short on resources and high on risk factors. Smoking and poor diets, for example, likely contribute to many causes of mortality. But, many experts argue that these so-called lifestyle factors shouldn’t simply be viewed as choices people make that keep them unhealthy and that they’re only a small part of the bigger picture.

Late last year, Army veteran Jimmy Edison stood up at St. Matthew and asked the congregation to pray for him. He was having another procedure in Tuscaloosa that week, something related to the open-heart surgery he’d had several years before. The church had been supportive in recent years, sending food to the house and praying for him and his wife, Dionne, after Jimmy’s heart trouble started, and they’d been moved by the warmth of the congregation to become members. After the service, Edison listed the bad habits that had led to his heart condition. He’d started drinking heavily on his days off in the Army, smoked since he was a teenager and always been a self-declared troublemaker who lived life hard.

After a 2010 heart attack, Jimmy’s drinking was so bad that he said they gave him beer at the VA hospital, afraid he’d get delirium tremens. Even so, he said his diet was the hardest habit to change. “I was a prolific drinker and smoker, and I had no problem giving that up. But the fried food, that’s the real problem,” Edison said. Sitting in the fellowship hall after the service, he described in glorifying detail the fried pork chops he missed so dearly, before explaining that his mother had also suffered from hypertension, diabetes and heart diseases. That family history has him convinced that there’s a genetic factor to his heart disease, though his diet and drinking likely made things worse. “It was like, I knew I was at risk, but I chose to play Russian roulette. I can’t say I didn’t know,” Edison said.

The stress that evolves from years of social disadvantage can reinforce a host of habits that are contributing to the highest incidence of diabetes and obesity in the country, said Alana Knudson, co-director of the Walsh Center for Rural Health Analysis at NORC, a research organization based at the University of Chicago. Food is “how you self-medicate. Sometimes we talk about people like they are doing this to themselves. But the reality is a lot of these people have endured some pretty challenging situations.”

Cultural norms play a role as well, and residents of the Black Belt are less likely to get regular exercise than people just about anywhere else in the country. Some of this is environmental: Humid, 100-degree summer days combined with intermittent electricity make it hard to do much of anything, let alone go for a walk. Monika Safford, a professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, spent 12 years at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, researching diabetes and heart disease. She said that in surveys she’s done in the Black Belt, many people respond that they get no exercise whatsoever on most days. “It was common when we were doing trials for people to tell us they drove down the driveway to get their mail,” Safford said.

People in the Black Belt don’t have higher mortality rates for every cause of death, but the causes that disproportionately affect them are telling. A growing body of research has found that generations of economic and social disadvantage can increase the risk of neonatal mortality. As extremely effective treatments for HIV were developed, mortality related to AIDS plummeted across the country, but it remains higher in the Black Belt than in most other places (as does HIV prevalence).

And cervical cancer, largely preventable, is more prevalent and deadlier in the region than in the nation at large.

Doreen Smith. Johnathan Kelso

Down the road from St. Matthew, Doreen Smith lives in a trailer left to her by her grandparents. She went to a doctor in Demopolis in 1992 when she was pregnant with her first child at age 16 and has taken each of her children to him since. She’s been told that to get prenatal care, she needs to go to Tuscaloosa, but with only intermittent access to a car, she said that’s always been too far. “Oh no, I’m not going all the way to Tuscaloosa.”

As a result, prenatal vitamins and the occasional checkup are the only care she’s received for most of her pregnancies, she said. Both teenage pregnancy and lack of prenatal care are considered risk factors for low-birthweight babies and other health concerns. But some studies have found that prenatal care doesn’t explain racial disparities in infant mortality, which is higher among newborns of middle-age black women than it is for newborns of white teenagers. Poverty, stress and trauma, as part of the cumulative health of a mother before and after birth, likely also factor into pregnancy outcomes.

But health in the Black Belt hasn’t been stagnant. While infant mortality is higher there than almost anywhere in the country, it’s a fraction of what it was a few decades ago. The same goes for heart disease, the leading cause of death in the U.S. Those improvements are attributed to several changes, including desegregation, better housing and education. In fact, one of the most robust literatures on the effects of racism on health comes from improvements to infant mortality among black babies after desegregation. Government programs have also played a role, namely the birth of the community health center movement and Medicaid, which was created in 1965 to cover pregnant women, children and people with disabilities. Both government efforts coincided with the civil rights movement and other programs that sought to undo the effects of racism and poverty throughout the country, particularly the rural South.

But there is still a lot of need today. Spencer is trying to tackle it from two angles: helping people change their habits and working to stabilize and improve struggling rural hospitals. They are long-standing issues, but he remains hopeful they can change. “We just really have to galvanize interest in the area,” he said.

In several upcoming articles, we’ll detail the complicated history of safety-net programs, such as Medicaid, in the area and illustrate how lack of access to health care continues to be an issue. Improving health in the Black Belt means recognizing the root causes: persistent poverty and lack of economic mobility, the challenges of living in rural America and a changing economic landscape that requires better education. It will also mean wrestling with social demons, including some that go back centuries.

[This story was originally published by FiveThirtyEight.]