Pollution takes heavy toll on Bay Area children with asthma

Each year, asthma attacks send tens of thousands of California children to the emergency room. Some are admitted to the hospital for days. In 2010, the state had more than 11,000 such admissions, costing an average of $19,000 apiece. Pollution plays a role.

Staff writer Katy Murphy and photographer Alison Yin produced this project for The Oakland Tribune as part of a 2012 National Health Journalism Fellowship. Other articles in the series include:

Deja Tyler, 9, of Oakland, Calif., left, receives a physical examination from Dr. Almaz Dessie, a resident at Children's Hospital Oakland, Wednesday, Sept. 19, 2012 at the ATTACK Asthma Clinic. (Alison Yin/For Bay Area News Group)

OAKLAND -- The pediatric inpatient unit was quiet, except for the deep, relentless coughing. It was the sound of asthma -- asthma out of control.

Two of the children who'd spent the night there, oxygen sensors glowing red around their index fingers, were ill, one with a bad cold, the other with pneumonia. But they were confined to hospital beds for a different reason: Their lungs were screaming for more air. Their illnesses had likely caused their already-sensitive airways to tighten up, choking off the flow of oxygen. And so far, nothing -- not the quick-relief inhaler at home, nor hours of treatment in the emergency room -- was enough to bring their breathing back to normal.

"I don't understand why he's not getting any better," said Angelica Tanner, as her son, 6-year-old Johnathan, lay listlessly in the bed next to her seat. It was their 15th hour at Summit Hospital, in a unit run by Children's Hospital Oakland.

Each year, asthma attacks send tens of thousands of California children to the emergency room. Some of the patients face such severe and enduring symptoms that they are admitted to the hospital for days. In 2010, the state had more than 11,000 such admissions, costing an average of $19,000 apiece.

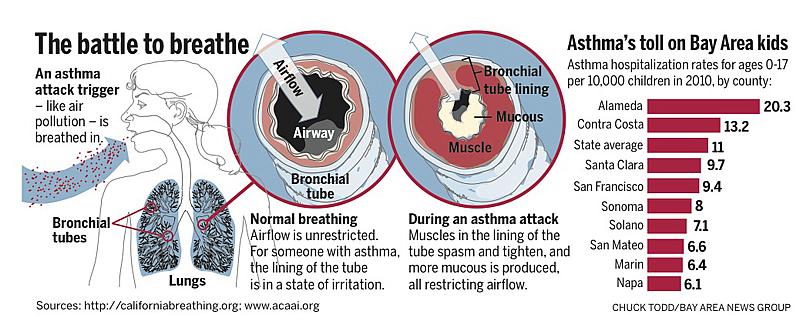

Exposure to pollution has long been a concern for families across the Bay Area, from the waterfront industries in Oakland and Pittsburg to the oil refineries in Benicia and Martinez to the clogged freeways that traverse the South Bay and Peninsula. In Alameda County, the asthma hospitalization rate -- 20.3 stays for every 10,000 children -- is nearly twice the state average and the third-highest in California, next to rates in Imperial and Fresno counties. Some Oakland neighborhoods sent children to the hospital two or three times as often as that.

These visits aren't just costly for society and the social safety net. When a child lands in the hospital or ER, it often means his asthma is out of control, a state of chronic inflammation that could compromise his health for years to come. An asthma misery index of sorts, these numbers reveal how many kids are missing out on school, physical activity and other hallmarks of a healthy childhood.

And all because of a disease that doctors say is largely treatable.

"I think it's every pediatrician's core belief that with adequate therapy, with early intervention, that the vast majority -- 80 to 90 percent -- of emergency department visits and hospitalizations could be avoided," said Dr. Ted Chaconas, a pediatrician who directs the hospitalist program at Children's Hospital Oakland.

But many children don't receive the early intervention they need or don't consistently take the medication that helps to prevent attacks. Then, when exposed to a virus, pollution, dust mites or something else that irritates their airways, their lungs revolt.

Tanner and her mother-in-law, Liz Stuecker, had been up most of the night. At 9 p.m., after Johnathan had coughed for 10 minutes straight, they took him to the emergency room at Children's Hospital. At 11 p.m., doctors put him on supplemental oxygen. By midnight, he still looked sicker than his mother had ever seen him. An ambulance whisked him to nearby Summit Hospital, where Children's leases 22 rooms, mostly for young patients' respiratory illnesses.

The San Leandro first-grader's asthma flared up often last year, costing him weeks of kindergarten and first grade. When he developed pneumonia last month, it was more than his lungs could take. It was the first time an asthma attack had sent him to the hospital.

Asthma on the rise

Asthma is the most common chronic illness for children in the United States. For reasons not well understood by scientists, it's becoming more common each year, now affecting nearly one in 10 kids. African-American children have experienced the sharpest increase: a 39 percent jump in the past decade. While rates of asthma rise, the costs of treatment are immense: $56 billion in 2007, according to an estimate from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

It's rare for a child to die from an attack, but it does happen. In 2009, 157 children younger than 15 lost their lives because of it, according to the American Lung Association.

Doctors say most asthmatic children can lead normal lives if their families get a handle on their condition and are able to treat it properly. Doing so, however, requires access to the right care and medication. It also demands vigilance. Each child is sensitive to different elements. For some, it's pets or dust mites; for others, it's allergies or cold air. Keeping them healthy involves figuring out what is likely to trigger an attack -- and avoiding those things.

But some of those triggers, such as vehicle pollution, can be tough to avoid. Cheaper rental units are also more likely to harbor mold, rodents or cockroaches, common asthma attack culprits. It's no wonder, then, that children who live near the Bay Area's perennially jammed freeways and power plants or in its low-rent homes are suffering the most. Contra Costa County, home to the industrial cities of Richmond and Pittsburg, ranked sixth, statewide, in trips children took to the emergency room.

For a child with asthma, Deja Tyler has a lot stacked against her. She and her mother live in West Oakland, an industrial section of Oakland encircled by freeways with a shipping port and heavy semi-truck traffic. Until recently, her mother smoked. Her older siblings had asthma as children, too.

During a fall checkup at Children's Hospital's outpatient asthma clinic, Deja said she'd felt better since her mother had quit the habit -- a decision primarily made for her health.

"Three weeks you haven't smoked?" a volunteer asked her mother, Rosalind Coleman. "Wow, give me five! That is awesome."

At Lafayette Elementary School, where Deja is in fourth grade, 23 percent of the students have been diagnosed with the condition, according to records from the Oakland school district.

Children in Deja's neighborhood were more than five times as likely as other California kids to be hospitalized for asthma in 2010, and twice as likely to be treated in the emergency room.

Deja is no exception. She had been rushed to the emergency room five or six times, Coleman said.

But Deja shook her head when asked if it was scary. By now, her mom explained, she knows what to expect when it's time to go to the ER. "She don't cry. She don't scream," Coleman said. "She just goes."

The right medicine

For Johnathan's mother, a medical laboratory technician who grew up in the Philippines, asthma was a strange and unfamiliar disease. When her son was first diagnosed, as a toddler, she didn't accept it right away, she said. She didn't give him his prescribed medicine regularly, fearing harmful side effects.

"It took me two years to understand how asthma really works," she said.

Now, Tanner said, she gives her son his medications religiously. Like many children with moderate to severe asthma, Johnathan takes an extensive combination of pills, sprays and inhalers to keep his asthma in check -- a monthly bill that, even with the family's good insurance coverage, comes to $100.

He takes one kind of medicine, known as a "controller," to prevent asthma attacks. He uses a "rescue" inhaler for instant relief when he starts to show symptoms -- in his case, a runny nose and teary eyes. Then there are nasal spray and steroids to reduce swelling from his reaction to environmental allergens, a common complication for asthmatics.

For controller medicines to work, they have to be taken as prescribed. Often, they aren't. Some people ration the medicine to make it last longer. Others stop taking it once they start feeling better, thinking they're cured, or when it doesn't seem to be working, or because they forget.

"If it's a choice between buying medicine or food, they are going to buy food," said Priscilla Ward, a respiratory therapist who volunteers at a free mobile asthma clinic, the Breathmobile.

Falling behind

Johnathan loves his school, James Monroe Elementary in San Leandro. But in the past year, his mother said, he has missed about five days each month. He tries to keep up through work his mom brings home, but sometimes he gets stuck. Addition problems that might otherwise come easily have stumped him.

And every time Johnathan misses school, it means one of his parents has to miss work. Tanner started a new job in November. In early December, she'd already had to skip a day of training to be with her son in the hospital.

"It's always a battle of wanting to work and at the same time, wanting to be with my sick kid," she said. "Of course, he always comes first, but we have to pay the bills."

A few rooms down, Monica Cabrera had set up a laptop work station between the hospital bed and the window. Her son, Veeonn Taito, an athletic 9-year-old from Oakland's Maxwell Park neighborhood, had his first major asthma attack in two years, after catching a bad cold.

Leaving his lunch tray barely touched on his hospital bed, he was on his knees, waving a video game controller, in a game of virtual bowling.

"Oh, yes! Finally, a strike!" he yelled.

His mother smiled. Then, she warned him that the nurses would take his video game away if he didn't settle down so he could get better.

At one point, Veeonn turned to her.

"If I play this game does it still mean I'm sick, or not?" he asked.

He answered his own question with a coughing fit that shook his entire body. "It really hurts," he said, when it finally stopped.

Veeonn's little brother, just 2 years old, has also been diagnosed with asthma. Last summer, the toddler was hospitalized and on oxygen for a week.

To keep her sons healthy, Cabrera regularly cleans the carpet to rid the home of dust mites. She even found a new home for their puppy after discovering it posed a health risk.

After a day in the hospital, Veeonn assured his mom he would take better care of himself, too. He promised he would stop running outside with no shirt, coat or shoes, knowing that cold air might set off another bad attack.

"I don't want to get sick and go to the hospital. I don't want to get admitted again," he told her. "That's why I want to wear a jacket and shoes and all of that."

He paused. "I don't want to die, either."

This story was originally published in the Oakland Tribune on February 9, 2013

Photo Credit: Alison Yin/For Bay Area News Group