Potent flavoring chemical vexes regulators, spurs litigation

One of these popcorn victims, suffering lung damage after exposure to diacetyl, just won a $7 million verdict in Denver. Read here about the continuing controversy around this food flavoring compound...

May 24, 2010

By Rita Beamish

Sniffing, Charles Campbell figured, was part of the job. He’d take a whiff of the flavor mix to make sure that his batches of cinnamon candy didn’t come out tasting like butterscotch, that the peppermints didn’t smack of wintergreen.

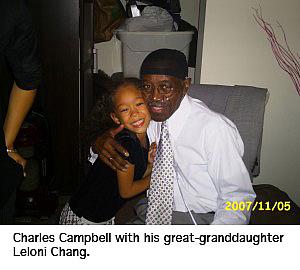

As he poured liquid flavoring into mixing machines at the former Brach’s Confections in Chicago, Campbell never imagined that his 30-year career with one of America’s favorite sweet makers could take a toll on his lungs. Nor that his pride in making candies for kids could foreshadow a health nightmare that would weaken him so much that he couldn’t even visit his own kids and grandchildren.

Campbell, who never smoked, eventually found himself tethered to portable oxygen, suffering a rare, irreversible and life-threatening lung obstruction called bronchiolitis obliterans. Physicians in 2000 began finding high rates among workers in microwave popcorn plants –- leading to the moniker “popcorn lung” –- and then among people who make butter flavoring for popcorn companies and snack food makers, like Brach’s.

Scientists fingered a compound called diacetyl, which occurs naturally in dairy products but also is part of a chemical cocktail used to make butter flavoring. The problem was not consumption of food containing the flavoring, but inhalation of its vapors by workers. Small airways in their lungs became constricted and scarred. With the threat identified, government regulators issued voluntary guidelines encouraging respirator usage as well as ventilation and enclosure systems to protect workers.

But after years of research and hundreds of worker lawsuits against makers and suppliers of butter flavoring, the government still hasn’t figured out what level of exposure is safe and how much makes people sick. Further, nobody has nailed down how widespread the hazard might be. And perhaps most disturbingly, after popcorn makers and other food producers changed their recipes for safety, government officials now are flagging the toxicity of substitute substances that essentially mimic diacetyl’s properties. In other words, the problem doesn’t stop with diacetyl.

* * * * *

“That story is still evolving because unfortunately sometimes people will use the substitutes without going through the toxicological background that is necessary,” said Lauralynn McKernan, senior environmental health officer at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). The agency, a branch of the Centers for Disease Control, will include the emerging science on substitutes in a broad review of diacetyl that is due out later this year and is expected to recommend a diacetyl exposure limit.

Both California officials and the federal NIOSH are working on regulations specific to diacetyl, and now are grappling with the question of substitute chemicals. NIOSH investigators in November reported that reformulated buttermilk flavoring supplied to a General Mills bakery mix plant in Los Angeles contained ingredients potentially as toxic as the diacetyl they replaced. The toxins were not listed on the safety sheets they came with, NIOSH found. The company used protective ventilation and respirators, but workers had higher than expected rates of asthma and shortness of breath.

“The difficulty in trying to regulate diacetyl is it forces flavor manufacturers to use these similar molecules with one more carbon, two more carbons, when the toxicity is probably the same,” said Kathleen Kreiss, head of NIOSH field studies on respiratory disease. A further complication in evaluating health effects is that workers may not show symptoms until after months or years of cumulative exposure. Employers often don’t know what their workers are exposed to, so doctors have trouble linking illness to the compounds.

Additional unknowns involve diacetyl’s interaction with other potentially harmful flavoring substances. A NIOSH study in 2008 found that the metabolism of diacetyl changes in the presence of butyric acid, a common chemical in butter flavorings, and becomes more harmful.

* * * * *

Popcorn lung faded from the front pages after popcorn giants including Orville Redenbacher, ACT II and Pop Weaver announced “no added diacetyl” in their microwave products two years ago. California regulators drove down usage with a voluntary program involving flavoring companies, and federal officials issued non-binding worker protection guidelines. The Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association urged its members to reduce use of diacetyl. Food makers say their protective systems have improved.

Nonetheless, politicians and government officials say an enforceable limit on diacetyl use is needed, a regulatory fix that also is supported by food industry representatives. One-time critics who now hold key positions in the U.S. Department of Labor yanked the go-slow Bush administration approach last year and announced the Obama administration would set a first-ever enforceable standard for diacetyl.

Labor Secretary Hilda Solis, who as a member of Congress had pushed for speedy government action when two flavoring workers contracted lung obstruction in her California district, noted three deaths had been linked to the flavoring compound. So far:

- • OSHA cited diacetyl regulation as a top priority last fall. A leading critic of Bush’s policy, David Michaels, now heads the agency, but he acknowledged time-consuming regulatory hoops. “OSHA is committed to protecting workers from the serious hazards associated with exposure to diacetyl,” Michaels said in a statement issued through his press office. “However, numerous steps in the regulatory process mean OSHA cannot issue a rule as quickly as it would like.” The agency anticipates October peer review of a health risk analysis that will underpin the regulation. It is considering whether to include diacetyl substitutes. In the meantime it has a special program to inspect 83 facilities that make diacetyl-containing flavorings. A similar program issued citations at 18 of 35 popcorn plants inspected in 2008.

- • Some in Congress want quicker steps. “I am concerned that OSHA has not acted fast enough to compel employers to reduce workplace exposure to this deadly additive,” Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) wrote to Solis in November. “Workers and their families should not remain unprotected any longer.”

- • California is closer to issuing protective rules that would affect companies using flavoring with more than one percent diacetyl. They would have to employ respirators and workplace controls and provide medical surveillance of employees. The state estimates 30 flavoring companies and potentially more than 4,000 food manufacturers would be affected, although many may have stopped using diacetyl. Some but not all have implemented recommended worker protections. The regulation, expected by summer, likely will include substitutes, said Len Welsh, head of California’s Division of Occupational Safety and Health. “We want to make it as difficult as possible to switch to an unknown and hope for the best,” Welsh said. Although new cases of bronchiolitis obliterans have dwindled in California, Welsh is tracking 45 workers with other lung illness that could be linked to diacetyl exposure.

- • NIOSH is trying to learn about diacetyl exposure at food factories beyond popcorn and flavor companies, such as baking and snack firms. Many companies have refused to let the researchers in.

- • The Food and Drug Administration is reviewing a petition that challenged its “generally recognized as safe” designation for diacetyl in food. The request was submitted in 2006 by OSHA’s Michaels when he was head of George Washington University’s Project on Scientific Knowledge and Public Policy. “While it is extremely unusual for FDA to contemplate food ingredient regulation on the basis of inhalation concerns, we have not ruled out any regulatory option,” said FDA spokesman Michael Herndon said.

* * * * *

Aside from worker illness, lung obstruction cases have emerged among four or five voracious popcorn eaters who blame their disease on vapors from the microwave product.

Popcorn was a staple for Debbie Daughetee. She popped at least two bags a day during long, intense hours as a Los Angeles writer and TV producer. Too tired to make dinner, she’d turn to popcorn at home. “It was quick, easy, filling and it didn’t have a lot of calories,” she said.

Over time, Daughetee became weak and short of breath, and lost her writing focus. Eventually doctors diagnosed bronchiolitis obliterans. Three years working in movie theaters again exposed her to butter flavoring, further endangering her health, she claims in lawsuits against several flavoring and popcorn companies. The suits are filed in Iowa federal court and Los Angeles County Superior Court.

At 53, Daughetee’s days of dancing, hiking and scuba diving are a memory, along with her dreams of being an executive producer. Taking a shower tires her. “It makes me incredibly angry,” she said.

Litigation by sick workers continues across the country. In a bankruptcy case involving chemical maker Chemtura, a major producer of diacetyl, 375 people have submitted claims asserting health effects due to diacetyl exposure.

Still it’s likely that many people don’t know they were exposed or that their physicians don’t know to ask them about the exposure and link it to their illnesses, said B. James Pantone, an attorney representing an Orange County flavoring worker who lost 70 percent of his lung capacity. “People who work around food don’t think of it as a dangerous substance. They think of it as food,” Pantone said. “Are there more cases? I think they’re going to be popping up for years.” But, he added, many will never be identified.

At least five of Charles Campbell’s co-workers at Brach’s developed severe lung injury, said Ken McClain, whose Independence, Mo., law firm specializes in popcorn lung cases. He said the firm represents 500 people in 300 diacetyl cases nationwide, and has settled many others including Campbell’s. It won trial awards totaling $60 million for another handful of clients.

“The extent thus far has been far more than anyone guessed and the number of potential people who are exposed numbers in the thousands,” McClain said. “What impact it’s having on a variety of occupations and uses is yet to be determined.”

Industry representatives say general food manufacturers have not seen workers’ compensation claims or illness patterns to indicate a widespread problem. “The presumption that latent cases of fixed obstructive lung disease would be discovered throughout food manufacturing has not been borne out in spite of several years of experience,” the Grocery Manufacturers Association told California regulators in complaining the state’s proposed rule was unnecessarily broad.

The association, which supports the idea of a diacetyl limit, said its members generally use flavorings with far less than one percent diacetyl. Food production workers are not continuously exposed to butter flavoring because bakers and food companies mix a variety of products and not all contain butter flavoring.

Some health experts counter that without active screening of employees, severe lung obstruction is frequently misdiagnosed or overlooked. “No one really knows,” said David Egilman, an occupational and internal medicine specialist who has diagnosed many brochiolitis obliterans cases and has testified as an expert witness. “Some people have gotten better after the exposure stopped and some people have gotten worse. You can’t say that there’s a particular pattern. There’s not enough data.”

He and California’s Welsh also portrayed the diacetyl problem in a larger context. Said Welsh, “I don’t think it’s the last that we’ve heard of this issue. There may well be other flavorings that turn out to be problematic. This one is an attention grabber because the illness you get is so dramatic and so life threatening. There’s an array of other flavorings that I believe are going to have pulmonary impact because of occupational exposures.”

* * * * *

Charles Campbell’s illness robbed him of retirement plans to travel and see family. “I look at other people enjoying life. I can’t do nothing,” he said, his weak voice punctuated by coughing. “My body is deteriorating.”

Uncomfortable in bed, he sometimes sat all night in his chair. But he didn’t complain about his pain, sitting day after day in his home outside Chicago, watching his beloved Chicago teams on TV. Last Thanksgiving, his five children, with kids and grandchildren, came to visit from around the country. “I just thank God I’m still here,” he said later.

In early April, Campbell mustered his strength to drive a short distance for replacement oxygen. He pushed his slight frame out to his new Hummer. Then, he turned and handed his son the keys.

“I knew then that it was bad,” said his wife, Natoma.

At the hospital the next day, he struggled to breathe. Two days later, on April 4, Charles Campbell died at 68. He was not, his wife said, ready to go.

Rita Beamish is a journalist who has covered national investigative and environmental stories for many years.