Powerful lawmaker calls for juvenile justice review in wake of Herald series

This article and others in this series were produced as part of a project for the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism’s National Fellowship, in conjunction with the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

At this juvenile justice program, staffers set up fights — and then bet on them

Dark secrets of Florida juvenile justice: ‘honey-bun hits,’ illicit sex, cover-ups

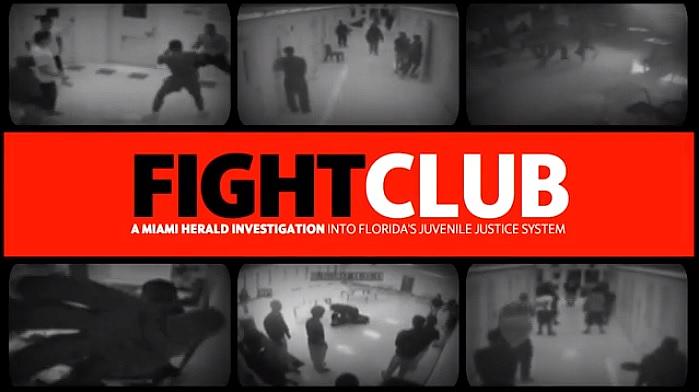

FIGHTCLUB: A Miami Herald investigation into Florida’s juvenile justice system

By Mary Ellen Klas, Caitlin Ostroff and Carol Marbin Miller

TALLAHASSEE -- The lawmaker who oversees a powerful criminal justice committee said he will lead a much-needed reform of the state’s juvenile justice system in the wake of a Miami Herald series that detailed the existence of a mercenary system in which detainees are given honey buns and other treats as a reward for pounding other youths.

Sen. Jeff Brandes, a St. Petersburg Republican who is the new chairman of the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Criminal and Civil Justice, said he believes the state is ready for reform.

“It gives me pause. There is a lot of work that can be done,” Brandes said at a meeting of the committee Wednesday, the day after the series appeared online. It was being published in print Sunday.

“There are going to be many tough questions that we’re going to be going through in the next committee weeks,” Brandes said.

On Tuesday, the Herald published a six-part series, Fight Club. Among the findings: the widespread use of unnecessary and excessive force; officers and youth care workers who outsource discipline by using detainees as enforcers; sexual misconduct by staff, some of which goes unreported; and neglect of the medical needs of teens, who are sometimes called fakers when they are in fact ill.

One of the root causes of such misconduct, the Herald found, is the low pay of youth workers. The state offers starting detention officers $12.25 an hour to protect and supervise youths. That’s $25,479.22 a year for a new recruit. Private contractors who oversee programs where detained teens serve their sentences often pay less than that. TrueCore Behavioral Solutions, the largest provider, offers new hires $19,760.

Sen. Jeff Brandes

Brandes said he supports a proposal by the agency and Gov. Rick Scott to hike the salary of current detention officers, saying “there is a systemic problem at the Department of Corrections and the Department of Juvenile Justice on salaries.” The increase would not raise starting pay.

TrueCore, which would not be bound by any salary increase imposed by the Legislature, said it might be inclined to do the same.

“Yes, we would consider that recommendation from Gov. Scott.” said Dina Shehata, TrueCore communications director.

“There’s no reason we’re paying people to watch these kids less than I’m paying my babysitter at home to watch my three kids,” Brandes said. “Many of these circumstances are much more difficult and so we need to look at that and probably do an entire review of the system based on this report.”

Brandes brought Department of Juvenile Justice Secretary Christina K. Daly before the committee on Wednesday and gave her an opportunity to respond to the Herald’s findings. He asked her to return to the committee in two weeks to address the Herald series in greater detail.

“I stand before you today to say that what is printed in the Miami Herald is not representative of what this system is,” Daly said. “This system is made up of thousands of dedicated staff who come to work every day to care for children and to take everything that we need to do to change the lives of these children.”

She added: “I will not deny, or discredit or downplay some of the horrible incidents that have happened. We respond. We hold people accountable. If we have to change policies or procedures, we do so. But it is not representative of this system.”

But Sen. Jeff Clemens, a Lake Worth Democrat, suggested that the problems appeared to be more “widespread” than the agency was acknowledging, since the incidents involved a variety of programs across the state.

“It would seem to me that this is systemic, rather than an isolated incident that we could fix with a small policy change,” he said.

Daly said there was no agency-wide problem. “I think what this has done is highlight critical incidents that happened over decades.” She noted a pilot project the agency is implementing using a newly developed model from Georgetown University and concluded: “Florida has some really great practices and procedures.”

Clemens noted that “employees in these privatized facilities are paid far less than they would in public facilities around the country” and suggested there were “glaring holes that need to be fixed” in the hiring practices of the private vendors.

“We are working with the providers to see how they could strengthen that,” she said.

After the Herald requested personnel and hiring records, the agency quickly implemented a new system for backgrounding job candidates, requiring a thorough investigation into the criminal records and work history of prospective employees. The Herald found numerous staffers with criminal or questionable backgrounds.

Daly has acknowledged, though, that her department hasn’t yet insisted that private operators embrace the same reforms. In fact, the agency can’t do that without signing new contracts.

“Ultimately, I would imagine that it would be something we put into their contract,” she replied. “But we’re in the process right now because they all have different hiring practices.”

Sen. Jose Javier Rodriguez, a Miami Democrat, also raised questions about the agency’s dependence on private contractors at all of the programs where youths are sent after they are adjudicated.

“If we don’t have the capacity here in Florida to ensure the safety of kids who are in detention centers or residential programs, shouldn’t we be revisiting this use of privatization in our system?” he asked.

Daly said the system was privatized by the Legislature. She said she didn’t know whether lawmakers voted to outsource the program in order to save money — a question Rodriguez asked.

“We have done a tremendous amount of work on contract monitoring, and management and procurement,” she said.

“Any time an incident happens, we do either a management review, an administrative review or an investigation. We have put tools in place to make sure we are providing the proper oversight.”

Clemens later commended the department for making positive changes by moving away from incarceration and towards treatment. But he also called the Herald’s findings the kind of “institutional problem that is the direct result of privatization.”

“We continue to farm out critical state duties to groups whose sole responsibility is to make money and turn a profit,” he said. “They pay their people poorly. They hire people who probably shouldn’t be in these positions and they make money off of skimping in critical areas. This to me is Exhibit A why some of these critical functions should be run by the state, which has more accountability to the public.”

Daly said she is proud of the reduction in the DJJ budget during Gov. Scott’s time in office. She said the agency has been reduced by $75 million since 2010 — $20 million of it went into early intervention and diversion services.

Brandes said the report calls for more answers.

“We are going to do a deep dive,” he said after the meeting. “We need time to understand and ask questions internally before we ask questions of Secretary Daly and have a little distance between the story and the question period.”

“I’m hopeful all the members of the Senate will spend the next couple of weeks reviewing it, asking questions, and then bringing back a portfolio of questions to ask the secretary, on the record, before the committee.”

Later Wednesday, the Broward County Juvenile Justice Circuit Advisory Board also met and members briefly discussed the Herald series. Gordon Weekes, chief assistant at the Broward Public Defender’s Office, arrived for the 3 p.m. meeting 15 minutes early, placing copies of part of the series at each spot on the conference room table. He told the board the series was heartbreaking and accurate. “When I read that report, and read how widespread these issues are throughout the entire spectrum of DJJ, it is broken to the very core,” he said.

On Friday, the advisory committee for Miami-Dade County took up the Herald series with Gus Barreiro, a former lawmaker and DJJ official, saying the problems have been going on for some time.

Marie Osborne, the Miami-Dade chief assistant public defender who is the board’s chairwoman, asked if someone from DJJ in the room or on the phone would like to add their thoughts. None did.

But Frank Manning, a DJJ chief probation officer, said the department is open to taking recommendations.

Barreiro said he plans to recommend that DJJ looks at how organizations that serve as alternatives to incarceration for kids, giving mentorship and support, like the PACE Center for Girls and AMIkids, do their training and implement similar methods at DJJ.

“It isn’t the Miami Herald trying to get at the agency and it wasn’t me as a legislator trying to get at the agency,” he said. “At the end of the day, this could be any of our children who end up in this facility.”

[This story was originally published by the Miami Herald.]