Rapid-detection DNA test for valley fever clears FDA, but procedure could be 'uncomfortable' for most patients

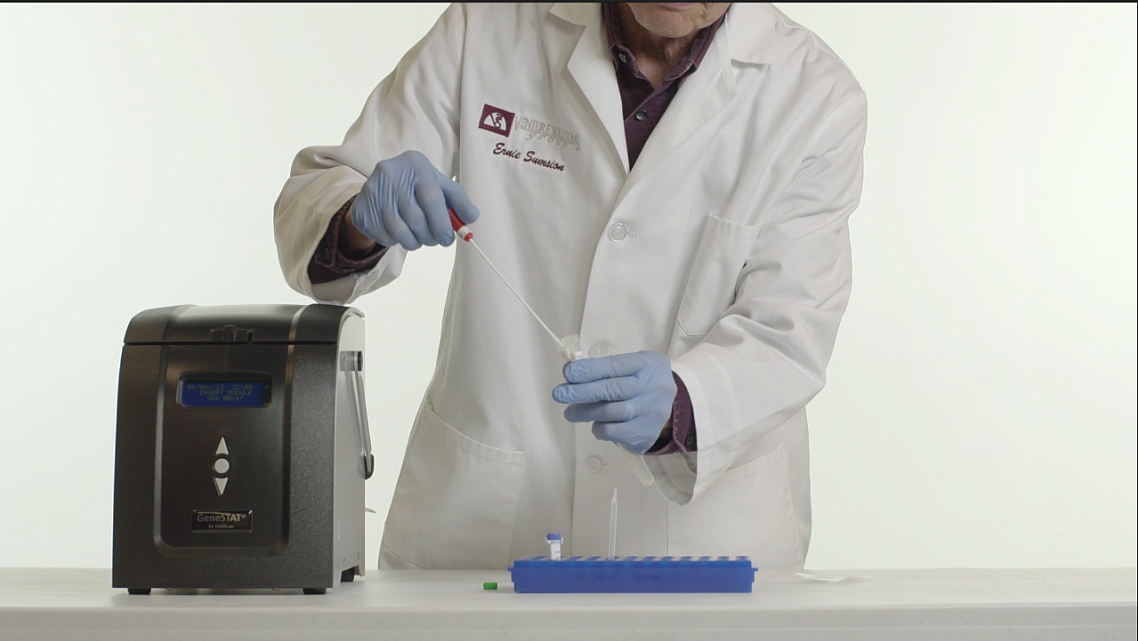

A lab technician works with a cocci sample to be used in a new testing instrument developed by DxNA LLC. that promises rapid, accurate detection.The specimen would be inserted into the machine, pictured to the left, and a diagnosis would be determined in about two hours.

CREDIT: DxNA LLC

Shannen Smotherman had trademark symptoms for valley fever.

She developed an awful cough, a fever and flu-like symptoms in early 2015. Then extreme fatigue set in. She would sleep all day, waking only to pick up and drop off her kids from school.

Despite that, all the tests doctors performed for valley fever — or coccidioidomycosis, the fungal disease endemic to Kern County and the southwestern United States — returned negative.

At one point, Smotherman began to doubt whether she had cocci or something worse. She wasn’t sure what was wrong with her.

Smotherman’s body wasn’t creating antibodies to fight off the disease, a rarity among patients that poses difficulties with the way doctors test for valley fever. If there are no antibodies, doctors have no way of confirming the disease’s presence. They were stumped.

All the while, she was getting sicker.

Like others, Bootleggers manager Shannen Smotherman, has valley fever, but her body doesn't produce antibodies, making detecting her sickness difficult with traditional testing. A new rapid-detection DNA test that cleared the FDA this week promises to allow doctors to more quickly identify the disease in people like Smotherman.

CREDIT: Felix Adamo / The Californian

“It progressed very rapidly in my lungs to the point where it created a hole the size of a grapefruit. Doctors said it could be cancer or tuberculosis, then released me from the hospital on zero medication and it continued to grow,” Smotherman said. “If you test positive, you have an easier path of how we treat this. Accuracy would have prevented a lot of headaches.”

But tests used to determine whether somebody has valley fever aren’t the most accurate. Current blood tests measure the level of antibodies that the immune system creates to fight the disease, but aren’t advanced enough to identify the fungus itself in the body. They also frequently produce false-positives and sometimes require multiple rounds of testing.

That changed this week, after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration cleared DxNA LLC, a molecular diagnostics company, to begin using a rapid-detection test that identifies the coccidioides fungus, which causes valley fever, in the lungs. Researchers say it can return nearly 100 percent accurate results in under two hours. It’s a breakthrough for the orphan disease, which has historically seen little funding for research, even as case counts have spiked over the last two years.

“Up until now, we haven’t really had a rapid, easy-to-use, definitive test to determine whether or not a person has the valley fever fungus in their lungs,” said Dr. David Engelthaler, co-director and associate professor of the Pathogen and Microbiome Division at Translational Genomics Research Institute North (TGEN), which developed GeneSTAT technology used to make the test possible.

The molecular test targets specific information in the DNA of the coccidioides fungus, “so it gives a really strong positive result,” Engelthaler said.

Valley fever, or coccidioidomycosis (cocci for short), is caused by a fungus that grows in the soil throughout the southwestern United States. When disturbed, often through construction and agricultural tilling, fungal spores can become airborne, and when inhaled, cause valley fever. The majority of those who inhale the spore don’t get sick, but others develop flu-like symptoms, fever, cough, and in the rarest cases, the fungus can disseminate to the bloodstream or other parts of the body and lead to a lifetime of health complications, and sometimes death.

“Doctors oftentimes tell patients they will eventually recover from this. We’d rather be able to get the information in the doctor’s hands right away so they can make better decisions about treatment and managing patients,” Engelthaler said, explaining that the test could be especially helpful to Filipinos, Hispanics and African-Americans, all of whom are at higher risk for developing symptoms — and at higher risk to have the disease spread to the bloodstream, which can create a host of additional problems.

“If the patient is at high risk for disseminated disease, the doctors would know right away whether they’re infected and start appropriate treatment,” Engelthaler said.

Accurate as it may be, researchers don’t expect the new test to replace traditional blood tests.

A new rapid-detection test for valley fever developed by DxNA LLC. directly identifies the cocci fungus in the body for the first time. Traditional serological tests identify antibodies produced by the immune system to fight the disease.

CREDIT: DxNA LLC

That’s because the procedure is invasive. To get the cultures from the lungs, patients must undergo a bronchoalveolar lavage, meaning a doctor passes a bronchoscope down the throat or nasal passages, squirts fluid into the lungs and then collects a sample. The other option is for patients to be provided an inhalant that induces coughing to produce a sputum sample.

Engelthaler said those procedures could be “uncomfortable” for some patients.

“People aren’t going to go get bronchoscopies just to get this test,” said Dr. John Galgiani, director of the University of Arizona Valley Fever Center for Excellence. “It’s a group of patients who haven’t been able to be diagnosed any other way.”

In other words, the test would benefit people like Smotherman.

And while valley fever advocates are cheering the newest test as a positive step forward for cocci, it’s not the easy, accurate, rapid-detection test for which they’ve been rallying for years. They also don’t see many patients opting for a more complicated and uncomfortable procedure for faster results.

Traditional serology tests take between 48 and 72 hours, but some labs, including the Kern County Public Health Services Department laboratory, can turn around immunodiffusion tests in 24 hours and complement fixation tests in about three hours to confirm the disease in the body, according to Valley Fever Americas Foundation member Rob Purdie.

“If this test requires an outpatient room, I guarantee it will still be quicker to do an immunodiffusion or complement fixation test,” Purdie said.

The test could open doors, however, for researchers to create tests that are less invasive, Engelthaler said. If cocci could be detected in the lungs, why not in saliva?

It’s something TGEN has done some initial work on with dogs because they produce so much saliva, Engelthaler said.

“We have initial evidence that it can be detected sometimes in the saliva, so it’s an area of exploration,” Engelthaler said.

The real value in the new test, Galgiani said, is that labs can detect the fungus through a culture without needing stringent safety measures.

Cocci is dangerous, especially in isolated environments like a lab. Its potential for biological warfare has been explored by the U.S. and Russian militaries in the early 20th century, Galgiani has said, and it’s regulated along with anthrax and written into anti-terrorism legislation.

So in order to grow the fungus and study it — including for the purposes of determining a diagnosis in those who don’t produce antibodies — Bio Safety 3 facilities are required. Few labs have that designation.

The new test doesn’t require that type of lab, though, Engelthaler said.

“Growing cocci is a risky business,” Galgiani said. “The advance is that this test would allow the specimen to be processed immediately … and it’s safer because you don’t have to grow the organism.

DxNA officials say the instrument will be brought to market in January.

For more stories in this series, click here.