‘A sad wake up call’: COVID-19 has hit Pacific Islanders harder than any other group

This article is the second of a larger project produced by Kellly Puente for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 California Fellowship.

Her other stories include:

Members of the Fourth Samoan Congregational Christian Church of Long Beach worship on Sept. 5, 2021. The church this summer lost three of its members to COVID-19 in two weeks.

Photo by Kelly Puente.

As head of the Fourth Samoan Congregational Christian Church of Long Beach, Rev. Enoka Alesana had repeatedly urged his parishioners to get vaccinated against COVID-19.

But many were wary as false rumors spread that the shot could make them sick or even infertile, he said. The younger members, he said, were especially stubborn.

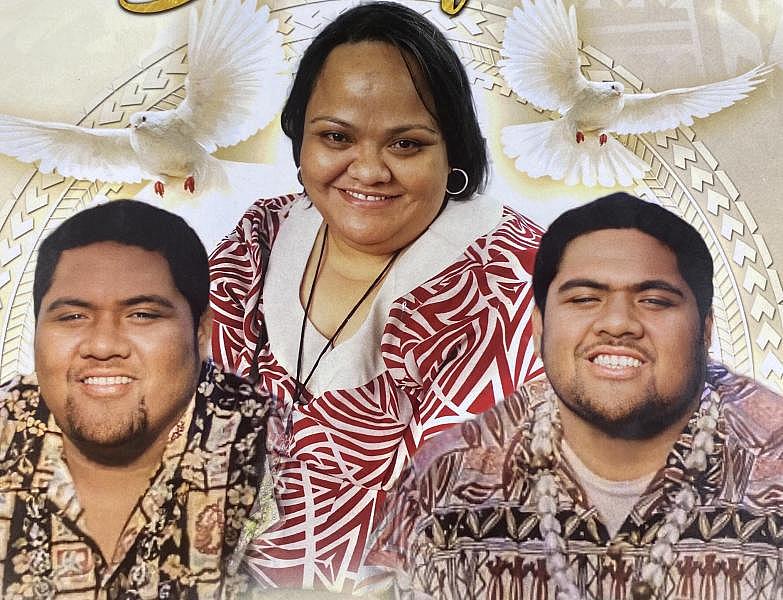

Mourners on Aug. 27, 2021 remember 23-year-old twin brothers Joel “Seali’i” Savea and Joey “Faleono” Savea and their cousin Emily “Fia” Memea, 40, who all died of COVID. The three were beloved members of the Fourth Samoan Congregational Christian Church of Long Beach. Photo courtesy of Fourth Samoan Congregational Church.

Joel “Seali’i” Savea, just 23 years old, was the first to die from complications of COVID on July 31. His twin brother Joey “Faleono” Savea died two days later, followed by their 40-year-old cousin Emily “Fia” Memea on Aug. 13.

On Aug. 27, the small Samoan church of about 200 parishioners in North Long Beach held its first ever triple funeral service.

Three white caskets draped in lace and white bouquets lined the walkway in front of the chancel, as grieving friends and family members paid their respects. The group sang traditional Samoan hymns while the reverend in a sermon in Samoan remembered the three as dedicated church members who died too soon.

Alesana said the twins and their cousin were not vaccinated before they fell ill in July, and the shock of losing three younger people to COVID so quickly prompted many in the church to rush to get their shots.

“I think most of them have finally realized the seriousness of it,” he said. “Almost all of our young people have now had their vaccines done. For our church, it was a sad wake up call.”

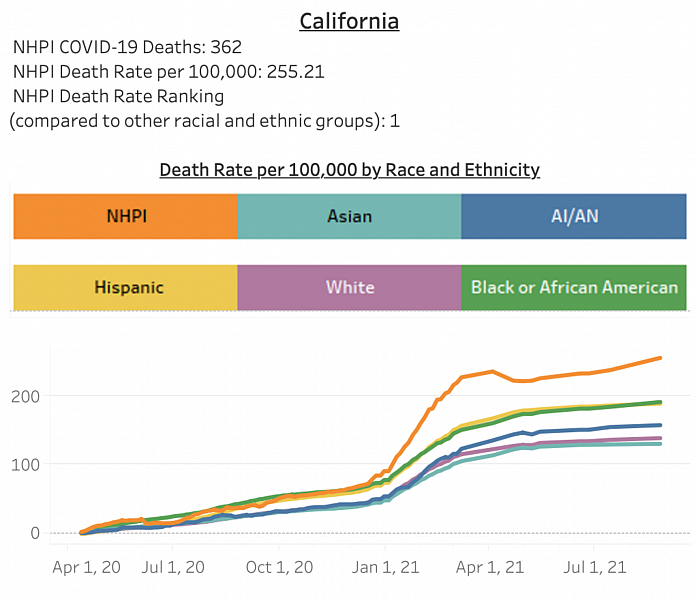

Source: NHPI COVID-19 Data Policy Lab at UCLA as of Aug. 26, 2021.

The group is more likely to get sick and die from COVID than any other racial or ethnic group, prompting advocates to call for a greater focus on health disparities in a community that is often overlooked because of their smaller population.

More than 360 Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders have died from COVID in California as of Aug. 26, for the highest death rate of any group, according to statistics from the NHPI COVID-19 Data Policy Lab at UCLA.

Long Beach has one of the region’s highest number of Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, with more than 3,000 residents, accounting for about .8% of the city’s population. The city’s working-class Westside neighborhood has historically high numbers of Samoans, Tongans and Chamorros from Guam, many of whom were lured by the prospect of good jobs and affordable homes in the last half of the 20th century.

Of the nearly 1,000 Long Beach residents who have died since the start of the pandemic, 23 were Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islanders as of Sept. 1, according to the Long Beach Health Department. That may seem like a small number, but it’s a large loss for a tight-knit community, advocates said.

Source: Long Beach Health Department

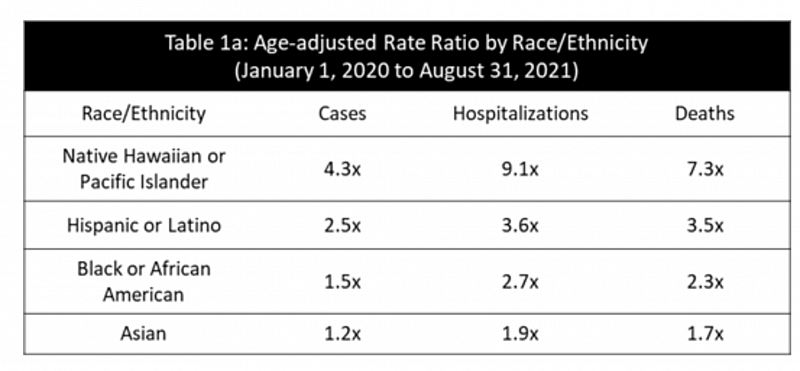

Overall, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders in Long Beach are seven times more likely to die and nine times more likely to be hospitalized for COVID compared to white residents.

Health officials say the reasons for the COVID rate disparities are similar to that of other communities of color.

Many Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders live in crowded, multigenerational homes that make it more difficult to quarantine. They have higher poverty rates and less access to quality health care. They also have higher rates of underlying health conditions including heart and lung disease, diabetes, asthma and obesity.

Alisi Tulua, project director at the Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Data Policy Lab at UCLA, said the pandemic has highlighted longstanding health disparities in her community and the need to focus on the unique risks of different subgroups.

“A lot of times we are buried under the AAPI (Asian American Pacific Islander) label and that has led to a lack of understanding and underinvestment in our community around health,” she said.

In May, Tulua co-authored a first-of-its kind study looking at COVID rates among the different Asian and Pacific Islander subgroups in California. The study found that Samoans had the highest death rate of all Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander subgroups with 182 deaths per 100,000 people, which is more than double the average for California. Tongans had the second highest rate with 124 deaths per 100,000, followed by Chamorro with 107 per 100,000.

Tulua said the study is important for counties and cities with large Samoan populations, like Long Beach, which can use the data to provide more targeted health care outreach.

Gone too soon

Like many Samoans, the Savea twins and their cousin all lived together in a close-knit, extended family of eight in a house in Torrance.

They regularly saw other extended family members, which is how the virus spread through the family like wildfire, said their uncle Van Epenesa, 47, who is head of the household.

Twin brothers Joey “Faleono” Savea and Joel “Seali’i” Savea, 23, and their cousin Emily “Fia” Memea, 40, all died of COVID this summer in a span of two weeks. Photo courtesy of Fourth Samoan Congregational Church.

For some, the symptoms were mild. Epenesa, who was the last one to get sick, said he lost his sense of taste and smell but was otherwise fine. Others struggled to breathe.

Joey, unable to catch his breath, was the first one to be rushed to the hospital, followed by Joel a few days later, and then Emily a few days after that.

All three spent about a week on ventilators and were intubated before they died, their uncle said.

The family was not able to say goodbye in person because of COVID restrictions. The twin brothers, who had been so close in life, were in different hospitals and unable to say goodbye, Epenesa said.

Within just two weeks, the family found itself planning three funerals and leaning on faith to get through the difficult time.

“We’re Christians, so we believe they’re in a better place,” he said.

The Savea brothers were born and raised in Southern California but kept close to their Samoan heritage and spoke the language fluently. They moved in with Epenesa, their mother’s brother, after their mother died from cancer in 2016.

Huge football fans, the twins both played football at Narbone High School in Harbor City and would engage in friendly fights over their favorite teams – Joey was a Ravens fan, while Joel was a Chargers fan.

“They were good boys,” Epenesa said. “Very humble.”

Emily, who the family lovingly nicknamed “Panda,” was like a sister to the twins and had helped to raise them.

Remembered as a sweet and loving person, she cooked and cared for the family and had recently brought her mother over from Samoa so that she could get better medical care, Epenesa said.

Epenesa said most of the family had been hesitant to get vaccinated before the illnesses, but they’ve since gotten their shots.

Sope Tuliau, the twins’ aunt, said she was very sick with COVID and got her vaccine as soon as she recovered.

“It was terrible for our family,” she said.

A grassroots vaccination effort

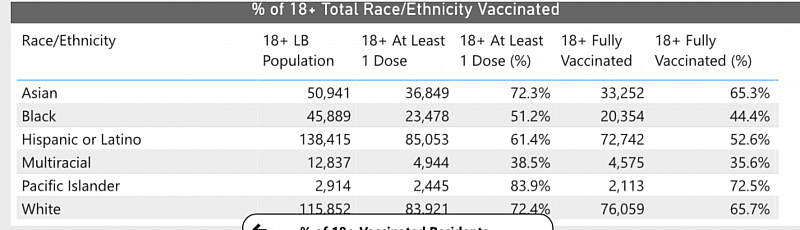

In one positive sign for the community, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders show higher vaccination rates compared to other groups. And advocates say that’s largely due to grassroots community groups and a push from faith leaders.

In Long Beach, more than 72% of Pacific Islanders over 18 are fully vaccinated, which is higher than any other group.

Source: Long Beach Health Department

While those numbers are promising, Heidi Quenga, vice president of the Pacific Islander Health Partnership, which focuses on COVID awareness in the community, said her group has been concerned about possible over-reporting of vaccination rates in the community as some multi-race individuals are checking multiple boxes.

The Los Angeles County Health Department, for example, does not have updated vaccination rates for Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders due to “likely inaccurate estimates,” according to its website.

Quenga said her organization has been working to verify vaccination rates across the state and believes the number is likely much lower than reported in some jurisdictions. Quenga said many counties still include Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders in one group with Asians, and she’s working to change that.

“We’re lumped under the AAPI umbrella when really it’s a huge region of the world with so many health differences that need to be acknowledged,” she said. “We’ve been swept under the rug for too long.”

In the early days of the pandemic last year, the group pushed the city of Long Beach, which has its own health department, to break out Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders from its COVID data. Quenga said they were initially told their numbers were “too small” but the city eventually changed its data.

“Long Beach was supportive once we made some noise,” she said.

Nora Balanji, an epidemiologist with the Long Beach Health department, said the city is looking at health and COVID trends among all of its races and ethnicities, and hopes to break out more health data for specific groups in the future.

A message from Fatih leaders

Quenga, a Long Beach resident of Chamorro descent, said community leaders acted fast last year when they saw the early grips of COVID on their people.

Groups like Empowering Pacific Islander Communities, the Southern California Pacific Islander COVID-19 Response Team and Pacific Islander Partnership banded together to provide culturally sensitive material and resources on the dangers of COVID. When the vaccine became available, they phone banked and canvassed door-to-door in cities with larger numbers of Pacific Islanders, offering information in five different languages.

Quenga said the group, now armed with more health data, is planning for a future health clinic in the Carson or Torrance area that would serve the unique needs of Pacific Islanders.

Rev. Enoka Alesana and his wife Maire head the Fourth Samoan Congregational Christian Church of Long Beach.

Rev. Pausa Thompson, head of the Dominguez Samoan Church in Compton, said he and other faith leaders regularly translate information about the vaccine in their Sunday sermons and work to educate their parishioners.

Thompson said he’s been to more than a dozen funeral services over the past year for people lost to COVID. He hopes to see less casualties as more people get vaccinated.

“The faith leadership has a huge responsibility in this pandemic,” he said. “I’ve been trying to use this platform to keep folks alive.”

At the Fourth Samoan Congregational Christian Church last Sunday, a few dozen members gathered for a regular service.

Donning all white hats, dresses and suit jackets for the tradition of first communion of the month, they sang classic Samoan church hymns through their masks, as the choir’s male baritone voices echoed the women’s high soprano.

Standing at the pulpit, Alesana once again reminded his parishioners of the dangers of COVID. After the serves, he noted the empty space in the church pews where three members once sat each Sunday, until suddenly, they were gone.

“It’s something that shouldn’t have happened, but that’s the reality of COVID,” he said. “It’s a great lesson to the Pacific People as well as Samoans to be aware and take it seriously.”

Editor’s note: This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 California Fellowship.

[This article was originally published by Long Beach Post News.]