Saltlick: “They don’t know they’re poor.”

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Rich Lord, a participant in the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2018 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Charges lodged in North Braddock arrest

Growing up through the cracks: The children at the center of North Braddock's storm

Where fighting poverty is a priority

Pittsburgh's neighborhood boosters face changing landscape

Current and former Rankin residents remember the past, envision the future

Rankin, Pennsylvania: Fighting 'the depressed mindset'

Growing Up Through the Cracks: Mapping Inequality in Allegheny County

A mother moves from McKeesport to Glassport to try to better her family’s chances

Growing up through the cracks: North Braddock: Treasures Amid Ruins

Pa. officials reverse course on local family support center funding

What it’s like to work in child care, raise your kids and just get by in the Mon Valley

Study: An increasing number of Pa. kids living in high-poverty areas

Nellie Brown, left, 6, lounges on the porch bannister as her brother Oliver, 7, fumbles with a set of toy teeth.

By Christopher Huffaker and Stephanie Strasburg

"There are two things we know,” said Mary Beth Brown one afternoon last November in the small Whoa Nellie Dairy store at her family farm.

“I’m going to die eventually, and we might lose this place.”

Ms. Brown, 37, has stage 4, metastatic breast cancer, meaning it has spread beyond her breasts — to her lungs and her bones. The place, which has been in her husband Ben’s family for more than 200 years, has not made a profit for the Browns and their three young children since they took it over from his parents four years ago. Dairy prices are simply too low, even after they began self-bottling part of their milk and selling it directly to customers.

Ms. Brown and her husband, 34, live every day worried that they will be the generation to lose the family farm, if they are unable to pay the loans they owe from buying the cows and machinery from his parents. Last year, they made just $10,000 to support themselves and their children Anthony, Oliver and Nellie, Ms. Brown said.

“We’re crossing our fingers that nothing’s going to break,” said Ms. Brown. And Mr. Brown does not get breaks: Twice a day, the cows need to be milked. He wakes up in the middle of the night to milk, and sleeps in shifts.

“We should be making $100,000, with how much he works,” she said.

Despite the sword hanging over their parents’ heads, “the kids are happy,” Ms. Brown said. “They go fishing, they shoot bows and arrows. They don’t know they’re poor.”

The Browns live on the border of Fayette County’s Saltlick and Bullskin townships, in the unincorporated post office location of Acme. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Saltlick is one of the Pittsburgh region’s municipalities where more than 50% of children are living in poverty — in fact, that describes nearly two-thirds of its kids. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette is featuring a dozen such communities in its ongoing series “Growing Up Through the Cracks,” including two other communities in Fayette County, seven in Allegheny County and one each in Westmoreland and Armstrong counties.

In January, the Post-Gazette featured the Mon Valley borough of Rankin, close to Pittsburgh, where vacant lots and violence conspire to keep families down and drain local resources. Rural poverty manifests itself differently but is no less pervasive.

In rural Saltlick, government services are hard to access. The local officials don’t see social services as their job, while federal and state benefits are funneled through the county seat in Uniontown, a 40-minute drive with no transit options.

For the Brown children, a strong social network, centered on their family and their church, has shielded them from great hardship. They know little of the challenges likely to come.

Even as they face Ms. Brown’s worsening prognosis, there is a lot of joy in the Brown household.

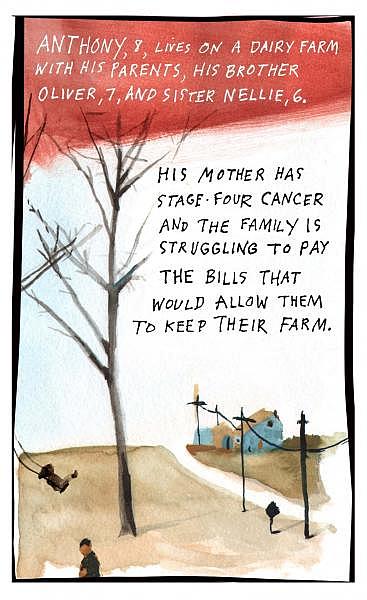

Shortly after New Year’s Day, the Browns’ children, Nellie, then 5, Oliver, 7, and Anthony, 8, excitedly showed off their Christmas presents. They included various knives, including hand-me-downs and county-fair purchases, Anthony’s first hunting rifle, and small gifts from Toys for Tots. Any time one brother brings out his knives, the other wants to show off his own collection.

One early April afternoon, two weeks after Ms. Brown had her ovaries removed to slow the cancer, Anthony, 8, excitedly described the “shelter” he and his siblings were building with their father on “Horseshoe Island,” an island in a nearby creek. Oliver, 7, played a Sonic the Hedgehog game on one of the two Kindle tablets he and his brother had received from their grandparents for Christmas. Nellie, 6, showed off how high she could swing, on the playset their father and uncle built, and the stuffed unicorn her grandmother had given her for her sixth birthday.

“Either an archaeologist or a farmer,” said Anthony, asked what he wants to be when he grows up.

Anthony likes to go looking for arrowheads in the fields and forests around their home, and he and his brother enjoy the work they do on the farm, gathering eggs and feeding the calves and chickens every day after school.

Anthony, who is in third grade, takes some classes at the fourth grade level, said his mom, and writes his own comic books. He’s a big fan of the works of Dav Pilkey: Captain Underpants, Super Diaper Baby and Dog Man. He also recently won fifth place in his grade in a regional Christian schools math olympics in Sewickley.

There’s one commitment Ms. Brown made clear: None of the children’s schooling will be disrupted by the farm work.

With her cancer, though, Anthony’s role on the farm will ramp up as he gets stronger. He will do the afternoon milking on weekends, work that she had expected to do herself once Nellie, who is in kindergarten, started school.

Until now, Nellie has mostly kept her mother company and acted as the mascot of the store that was named for her. But she too will have to start pitching in.

“Since Nellie turned 6, it’s time to figure out what she can do,” said Ms. Brown.

A Shelter on Horseshoe Island by Stacy Innerst

The allure of rural America

According to Dan Lichter, a Cornell University sociologist who studies rural poverty, the sort of strong social connections that the Browns have been able to depend on were once typical of rural areas, but are slipping away.

“That’s part of the allure of rural America — you have those strong bonds between family and friends that provide a safety net. That’s true, and that’s still true in some parts of the United States, but overall that’s much less true today than it was in the past,” said Mr. Lichter.

“The other side is that those social connections for some people are being frayed. You look at divorce rates, outmigration, non-cohabitation, all those things have increased in rural areas over the last 20 years,” he continued.

As big business has taken over agriculture, younger generations have moved to urban and suburban areas, where cities have consolidated their role as the country’s economic engines.

Agricultural consolidation is the pattern in Fayette: While farm acreage barely budged, more than 10 percent of the county’s farm operations disappeared from 2012 to 2017, according to the Department of Agriculture farm census.

On the other hand, even as people have left and networks like the Browns’ have weakened, there are still some ways in which the rural poor are distinct, said Mr. Lichter.

“Rural people are more likely to be disproportionately white, as opposed to minorities,” said Mr. Lichter. “The rates of poverty in rural minority populations are higher, but rural areas are higher proportion white.”

Saltlick is 99 percent white. Uniontown, the county seat and another community with high child poverty, is 15 percent black.

The rural poor are also often isolated, geographically and socially, and the poverty tends to be concentrated, Dr. Lichter continued.

“At the county level, the rural poor, particularly rural children, are more likely to live in communities that are disproportionately poor. They’re poor and they’re surrounded by more poor people,” he said. “It means that rural kids are less likely to be in areas that provide other kinds of resources: clean water, access to good schools, health care providers, social services, things of that type.”

While the highest-poverty municipalities in Allegheny County have child poverty rates estimated as high as 60%, the countywide rate is 15%. In Fayette County, it’s double that.

Bullskin, on one side of the Browns’ farm, is the “wealthy part of Fayette County,” said Nicole Mowry, while delivering soup and sandwiches to families in need, including the Browns, through a ministry she helps run at the Buchanan Church of God.

“They shop at Walmart, we shop at the dollar store,” joked co-congregant Ryan Martin. In Bullskin, an estimated 17% of kids are living in poverty.

Despite Saltlick’s poverty, its local leaders don’t feel that their job duties include addressing economic distress.

“We mostly do roadwork, parks and public safety,” said Greg Grimm, chairman of the Saltlick board of supervisors, after a board meeting last year at which they dealt with zoning and sewage violations.

Who does support the poor around here? Mr. Grimm pointed to private organizations in the region: churches, including the Buchanan Church of God and the nearby Indian Head Church of God, as well as the Indian Creek Sportsmen’s Club, which hosts fundraisers. Mr. Grimm belongs to the Sportsmen’s Club and the Indian Head Church.

Otherwise, aid to needy children is funneled through the school district.

Pastor Doug Nolt, of the Indian Head Church of God, explained local programs the church is involved in, including supporting a nearby food pantry, a “Warm Coats for Cold Kids” program organized by the schools and a weekend backpack ministry, which sends kids home from school with backpacks full of food. Almost all of Fayette’s schools give free breakfast and lunch to all students, so the backpacks cover the weekend. (The Brown children also receive free meals at school.)

Besides those ad hoc local programs, there aren’t a lot of options, said Pastor Nolt. “You have to go to Uniontown; there’s no satellite office, if you’re on relief, welfare, or something like that.”

“Some folks wouldn’t go to Uniontown for assistance,” said John Staranko, a lumber trader who helps organize the soup and sandwich program.

According to Mr. Lichter, takeup of government benefits like food stamps is particularly low in rural areas, “not only because of the stigma they associate with it, but also because of issues like transportation costs.”

Everyone knows everyone else doesn't have a lot of money

The Browns aren’t going to starve while they have the farm and can hunt — they freeze and can deer, so they have it year-round, and have chickens, a small herd of beef cattle and a larger dairy herd — but that doesn’t mean they never worry about putting food on the table.

“That day [Ms. Mowry] dropped off the soups, I didn’t have any food in the refrigerator,” said Ms. Brown.

And isolation is an issue. They used to get food stamps, but had them cut off a few years back because the state counted their full farm income as family income, even though most of it went to loan repayments and other fixed expenses. “I didn’t have the time or energy to go fight in Uniontown,” she said.

The Browns depend on Medicaid for Mary Beth’s cancer treatment; Ms. Brown’s parents for delivering milk, babysitting and watching the store when she is too sick to do so; and Mr. Brown’s brother for help on the farm. The house they live in is over 100 years old and has not been “updated,” Ms. Brown said, in 50.

They receive financial aid, paid by anonymous donors, for tuition at Champion Christian School, a nearby private Christian school which accommodates Oliver’s developmental disabilities — he’s a year behind, in first grade. During Ms. Brown’s cancer fight, family, friends and members of their church have raised money to pay for gas needed to get to Pittsburgh for treatment at UPMC Hillman Cancer Center, helped pay the small premiums required by Medicaid, and regularly kept the family fed, including bringing them a huge Thanksgiving spread, she said.

But the cancer has put the brakes on multiple plans by the Browns to get ahead of the low dairy prices. Cheese was supposed to be the next step. Ms. Brown took a cheese-making class, to expand past milk, eggs and beef. “We thought we were going to double our business with cheese,” she said.

Cancer intervened. She is too weak to do that work, and instead they depend on charity. “People giving us money has kept us afloat, because otherwise I’d be making cheese by now, really helping with the store.”

Even running the store now requires the Browns cutting into their narrow margins to pay friends and family, as Ms. Brown can only work one day a week, on a good week.

The cancer has also compelled Ms. Brown’s mother to quit her job. On Dec. 5, after they learned that the cancer had spread to Ms. Brown’s spine, her mother, Mary Lou Basinger, 63, stopped teaching Silver Sneakers fitness classes she had taught for 13 years in nearby Connellsville, where Ms. Brown grew up.

“I never got to go back,” Ms. Basinger said, after dropping off a lasagna at the Browns’ house.

Both of Ms. Brown’s parents often go with her to doctors’ appointments.

“It can be tiring, but I enjoy being here,” Ms. Basinger said.

“She made that sacrifice for me. It should be the other way around,” said Ms. Brown.

Ms. Brown’s parents have been dealing with a family member’s addiction for years.

“As soon as he got clean, I got diagnosed with cancer, so my parents have been dealing with this for so many years,” she said.

“Situations in life aren’t easy, but you deal, and you just have to have faith in God,” said Ms. Basinger.

Friends and family have run fundraisers for the Browns ranging from a spaghetti dinner to a golf tournament. In April, Nicholson Cancer Fund, based in nearby Connellsville, stepped in to pay two of Ms. Brown’s medical bills.

The Browns give back. When they run a corn maze at the farm in the fall, they give a discount to the local Head Start Program. The area around the cash register at the Whoa Nellie Dairy is plastered with flyers for fundraisers and raffles for various local causes.

“Everyone knows everyone else doesn’t have a lot of money,” explained Ms. Brown.

The takeaway: People have to care for each other, and those who receive should also give. “I’ve got a limited time,” she said, “to get these messages through to my kids.”

Christopher Huffaker: 412-263-1724, chuffaker@post-gazette.com or @huffakingit on Twitter.

This story was produced with assistance from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism‘s Data Fellowship. The Economic Hardship Reporting Project supported Stacy Innerst’s illustration.

[This article was originally published by the Post-Gazette.]