In the Shadow of San Diego: Environmental Health Hazards

Maria Martinez and her husband and three sons live in a colorful stucco home in a subsidized housing development called the Mercado a few blocks from San Diego Bay. Martinez works as a "promotora," one of the grassroots health promoters that many Latin American families depend on for advice. Her home exudes health and cheer: a bowl piled with fruit sits on the bright tablecloth, parakeets chatter from sparkling clean cages, the sea breeze blows through gauzy curtains on open windows. But as much as she strives for a healthy ambience in her home, as soon as she steps outside Martinez and her neighbors are confronted with an onslaught of environmental health hazards.

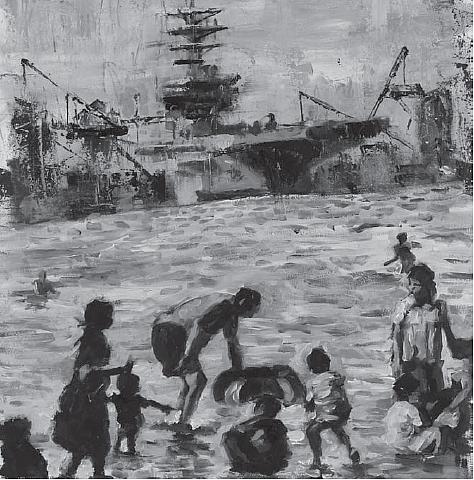

Their Barrio Logan neighborhood, a historic immigrant enclave, is right next to the West Coast's largest shipyard, the Port of San Diego, and various related industries.

In the Shadow of San Diego: Environmental Health Hazards

Maria Martinez and her husband and three sons live in a colorful stucco home in a subsidized housing development called the Mercado a few blocks from San Diego Bay. Martinez works as a “promotora,” one of the grassroots health promoters that many Latin American families depend on for advice. Her home exudes health and cheer: a bowl piled with fruit sits on the bright tablecloth, parakeets chatter from sparkling clean cages, the sea breeze blows through gauzy curtains on open windows. But as much as she strives for a healthy ambience in her home, as soon as she steps outside Martinez and her neighbors are confronted with an onslaught of environmental health hazards.

Their Barrio Logan neighborhood, a historic immigrant enclave, is right next to the West Coast’s largest shipyard, the Port of San Diego, and various related industries.

Diesel emissions from the ships and the constant parade of trucks and trains that serve the port pose a serious health risk to surrounding communities, with numerous studies linking diesel exhaust to increased incidence of cancer, lung disease, heart disease, asthma, and other ailments. Martinez’s thirteen-year-old

son has asthma that requires an inhaler and makes it hard for him to participate in gym class. She worries her five- and ten-year-old sons could also develop asthma.

Across the street from the Mercado is a warehouse where about thirty trucks a day — many from Dole — come to load and unload. Concentrated diesel emissions and loud grinding noises emanate from the idling trucks. Parents are terrified their children will be hit by the big rigs that squeeze precariously through the narrow street all day. Nearby residents can’t sleep with their windows open because of the noise, which means stifling hot rooms in the summer.

On surrounding blocks are storefront operations for chrome plating, welding, and other industrial tasks related to the shipyards. These industries are also known to release toxic emissions, with studies revealing elevated levels of nickel, molybdenum, tin, and antimony in the air. “We’re under attack by air, by land, and by sea,” says Maria Moya, an organizer with the Environmental Health Coalition, which works on both sides of the border.

The sediment around the Navy base and two adjacent shipyards — the National Steel and Shipbuilding Company and BAE Systems San Diego Ship Repair — was found to be among the most contaminated of bays and estuaries nationwide in a 1996 study by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. A 1997 study by state government scientists found more than half the bay was toxic to sea urchins and amphipods, and in the past decade a number of other studies by government agencies and private contractors have found high levels of PCBs, mercury, arsenic, copper and other contaminants in the sediment and in fish caught in the bay. The fish also had lesions and tumors attributed to the contaminants.

For many years, state regulators and environmental groups have been pushing for the contaminated sediment to be cleaned up, but the shipyard companies have denied responsibility and a lengthy regulatory process has dragged on. In December, the state water quality board is scheduled to finally issue a cleanup mandate to the shipyards, Navy, port authority, and several other responsible parties. But environmentalists are worried the orders won’t be strict enough.

The proposed shipyard site cleanup would cost about $100 million, and once it is ordered the responsible parties must decide how to split the cost. Along with the Navy and the two shipyards, these parties include the port authority, which is the landlord; Chevron and BP, which have fuel terminals at the port; and the city of San Diego, which emptied storm water into the bay.

The shipyard companies have argued that people don’t eat fish from the bay, hence the sediment contamination doesn’t pose an immediate human health risk. But a 2004 study by the Environmental Health Coalition and anecdotal reports indicate many immigrant families do indeed consume fish from the bay regularly.

“This is a very poor community, people have very few places to play, and fishing is one of the things they do,” says Moya, who got involved with the Environmental Health Coalition in the 1990s around its successful battle to end the fumigation of Dole produce at a facility that vented toxic methyl bromide emissions near an elementary school.

The coalition surveyed 109 fishermen at several popular spots. They found almost two-thirds of fishermen did eat the fish, despite signs in English, Spanish, Vietnamese, and Tagalog warning against fish consumption at some spots and in other spots prohibiting fishing. The coalition also found 13 percent of fishermen — and presumably their families — eat the fish skin, and likely also the fatty organs, where toxins are especially concentrated.

On a May afternoon, despite cool stormy weather, a small crowd of Filipino and Mexican fishermen catches fish off the pier next to the city’s Tenth Avenue port

terminal in National City, just south of the shipyards, where a massive ship was unloading sparkling new vehicles destined for the area’s famous Mile of Cars dealerships. Gabriel Munoz, fifty-three, a laborer, says he and his family eat the fish he catches. Asked if he is aware of the health risks, he shrugs and smiles.

A young Mexican fisherman who gives his name only as José says he never eats fish from the bay but he knows many families do, and some sell fish to their neighbors: “It’s just a way to make a living.”

Albert Ayson, a Filipino information technology worker, says he’s well aware of the risks, having studied environmental science in the past. “People give fish to their neighbors,” he says, noting he himself eats the fish since at sixty-two he figures he’s too old to worry about long-term health effects. “I want to tell them, ‘You’re polluting your bodies.’ But I don’t.”

Cesar Chavez Park on the bay is sandwiched between the shipyard and the port. A BNSF rail yard — where locomotives and equipment emit diesel exhaust — is also nearby. Latino and Filipino residents often fish off the pier in Cesar Chavez Park, continuing an area tradition celebrated in the park’s tile mosaics and a stunning steel sculpture. For the first half of the twentieth century, immigrants from Mexico, Asia, and Europe were drawn here to work as fishermen and in the neighborhood’s once-famous tuna canneries.

But now the bay’s fish are contaminated with mercury, PCBs, and other toxins that the shipyards and other industries once dumped freely. Despite warning signs, many families eat sand bass and Pacific mackerel from the bay, while on hot days children splash and swim off the trashstrewn rocks near the park. “It’s sad to know you have a beach but kids can’t use it safely because of the contamination,” Martinez says. “They can’t swim, fish, or play in the water. Many families don’t have cars so it’s hard to get to another beach.”

California Regional Water Quality Control Board executive officer David Gibson says the shipyards should have to clean the sediment up whether people are eating fish from the bay or not. “I assert anyone who wants to should be able to catch a fish from San Diego Bay and eat it without risk of cancer,” he said.

The Environmental Health Coalition and San Diego CoastKeeper want the shipyard companies to be forced to clean up a larger area than the water quality board has proposed. “It’s the precautionary principle,” says Environmental Health Coalition sediments campaign director Laura Hunter.

Environmental groups do not want to shut down the shipyards, port operations, or related businesses. But they do want them to use the best technology available to clean up the sediment and reduce ongoing pollution.

Jim Gill, a spokesperson for the National Steel and Shipbuilding Company, says the company has reduced its air emissions greatly and developed procedures to capture and clean almost all their wastewater. He also points to the corporation’s extensive recycling efforts and community cleanup events.

The Port of San Diego has also reduced diesel emissions through components of its “Green Ports” program, including providing electric power for one of the two cruise ships that are usually at berth and asking ships to voluntarily reduce their speed near the port, which significantly reduces exhaust. Port officials offer incentives for tenants — the industries — to reduce their water and energy use. They are subsidizing the repainting of ship hulls with paint free of copper, which leaches into the water. And the port authority is studying how to respond to the sea level rise expected with climate change in an environmentally friendly way. But many San Diego residents feel the cleanup efforts don’t go far enough.

Right near the bay and Barrio Logan is Chicano Park. It came into being after residents demanded getting the recreation area instead of a police station on the

vacant land below interlocking highway overpasses. The most striking features of the park are the murals that snake up the highway supports. Among the murals of Aztec warriors, modern labor activists, and other struggles in Chicano Park is a column painted with a sinister skeletal businessman, his jacket emblazoned with the names of bay polluters. “Toxics... Why Us?” the mural asks. It was part of a popular education campaign around bay pollution.

“One of the biggest victories we have is that more people are participating,” says Martinez. “These companies have the solutions in their hands, but they don’t want to do anything about it. Money is more important to them than our health. You can recuperate money, but you can’t recuperate the days of school a kid missed or the lost time with our families if we are sick.”