Suicide rate among Montana's senior citizens outpaces national figure

Billings Gazette health reporter Cindy Uken is a 2012 National Health Journalism Fellow. This article is part of a series examining the suicide epidemic in Montana. Other stories in this series include:

Suicide survivor: 'There was really no help for me and no hope'

Teenage girl fatally shoots herself days before '08 school year begins

Before a suicide, a mother's lament: 'Why can't I fix this?'

Miles City school administrators tackle problem of suicide

Play designed to help youth feel comfortable discussing suicide, feelings of despair

Suicide is 2nd leading cause of death among Montana youth

Veterans twice as likely to commit suicide as civilians

Veteran: 'I just always hoped that I would be in that freak car accident'

Veteran: 'You're taught in the military that you don't ask for help'

Some live with punishing chronic pain.

Some have lost physical function, or no longer have cognitive ability. Some have lost their lifelong spouse.

They are lonely, bored and depressed.

They are Montana’s senior citizens.

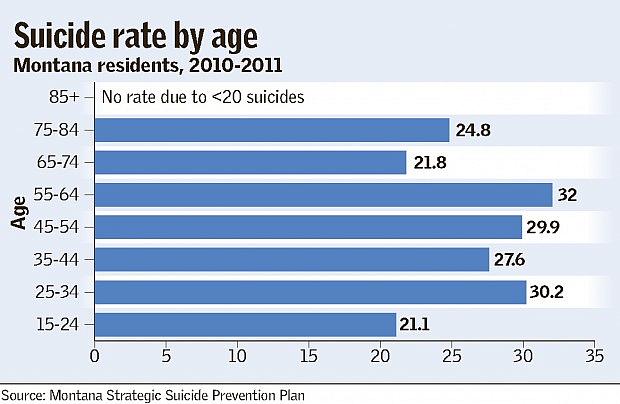

While they seem like the least likely candidates, the elderly are killing themselves with greater regularity than any other age group in Montana. That’s also true across the country, eroding the myth that teens run the highest risk of suicide.

Even though in 2010 the elderly, those 65 and older, made up 13 percent of the country’s population, they accounted for nearly 15.6 percent of all suicides, according to the American Association of Suicidology.

By the year 2025, nearly one in four Montanans will have surpassed the age of 65, jumping from about 100,000 now to 240,000. In fact, Montana is already projected to rank fourth in the nation in percentage of seniors by 2015.

And it's an increasingly vulnerable population. One senior citizen committed suicide every 90 minutes in the U.S., or about 16 each day, resulting in 5,994 suicides among those 65 and older.

In Montana in 2010, at least 41 Montanans over age 65 killed themselves, according to the Montana Office of Vital Statistics. This gives Montana a rate of approximately 25 suicides per 100,000 elderly, outpacing the national rate, which is about 15 suicides per 100,000 elderly.

The statistics play out every day in real time. As recently as Jan. 3, Billings police responded to a report of a 65-year-old Billings woman who hanged herself in her garage.

In Montana, the rates of suicide are highest among those ages 55-65. That's a group referred to as the “young-old,” those who are not quite elderly, but not middle-age either.

During 2010 and 2011, a total of at least 91 “young-old” Montanans killed themselves. More Montanans in this age group committed suicide than any other segment of the population, including teenagers.

The primary issue involved with elderly suicide is undiagnosed and untreated depression, which is not a normal part of the aging process, said Karl Rosston, suicide prevention coordinator for the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services. Depression is characterized by sadness, loss of interest, sleep disturbances, loss of appetite and loss of energy.

“Add the Montana issue of isolation, and you have a major issue,” Rosston said.

The tragedy is that good treatments are available for depression, said Dr. Yeates Conwell, a professor at the University of Rochester who researches suicide among the elderly. The issue isn't addressed for several reasons, including that older people tend not to talk about their mood. They tend to focus on their aches and pains and get limited time in the doctor’s office.

Americans get an average of 18 minutes with their primary care physician during each visit. Getting to the emotional state, underlying sadness and hopelessness, is often very difficult for the primary care doctor, Conwell said, especially when they are caring for someone with numerous medical conditions and medications.

Primary care doctors are critical in helping prevent suicide among the elderly because older people, especially older men, are reluctant to seek out and accept mental health services. But they are often seen by family doctors and nurses within days or weeks prior to killing themselves, Conwell told The Billings Gazette.

Seventy-five percent of suicide victims 55 and older visited a general physician in the month before the suicide. In fact, 20 percent see a general physician on the same day they kill themselves and 41 percent within a week.

“That’s one of the important lessons that teach us where we ought to be looking to help most,” Conwell said.

There is also a stigma attached with having depression in the elderly, said Dr. Patricia Coon, a geriatrician at Billings Clinic. Many elderly do not believe they suffer from depression or they don’t believe medicine is going to help.

“They think if they go see a psychiatrist they’ve got to be crazy or loony,” Coon said. “This is the group that fought World War II, came home very stoic and lived through the Great Depression. To them, it’s a sign of weakness to have a psychiatric illness.”

Even if they choose to see a psychiatrist, there are so few mental health professionals in Montana that patients can wait anywhere from two weeks to three months or longer to see a psychiatrist. In some corners of the state, there is one psychiatrist serving an immense multicounty area.

Other common risk factors among the elderly include the recent death of a spouse, loss of physical function, loss of cognitive ability, physical illness, uncontrollable chronic pain or the fear of a prolonged illness, perceived poor health, social isolation and loneliness. Major changes in social roles also play a role, such as retirement, loss of driving privileges, or loss of financial independence.

Some survive on meager fixed incomes and have incurred debt. They have no way of paying those bills and carry a tremendous sense of guilt. They feel as though they are shirking their responsibilities.

“They can get the feeling they are a sustained burden on others, particularly members of the family, like offspring, even grandchildren,” said Dr. Don Harr, who practiced psychiatry in Billings for decades. “They feel it’s a duty to cease being a burden on others.”

Social issues, financial woes and medical problems are ubiquitous, but there is no single reason that older people kill themselves, said Conwell. Suicide among the elderly is much more complex.

Society tends to discuss suicide in the elderly as an irrational act or an act of self-determination because of a desire to see its parents and senior citizens in the community as in charge, whole and capable, Conwell said. That, however, is not always the case.

“Mental illness is by far the rule,” Conwell said. “It’s the exception that an older person takes their own life without diagnosable psychiatric illness.”

The number of suicides among the elderly is a microcosm of what’s happening in the state overall.

During 2010, at least 227 Montanans took their own lives. Another 225 people committed suicide in 2011. That’s about 22 people per 100,000 residents, nearly twice the national average.

Montana’s suicide rate has ranked in the top five for more than three decades and most recently spiked.

In addition to the unique factors that contribute to elderly suicides, their plight is complicated by some of the same factors that contribute to the state’s overall high rate of suicide: a shortage of mental health professionals and facilities and the prevalence of firearms.

Guns are the favored means of committing suicide among the elderly in Montana, which ranks third in the nation for per capita gun possession. In general, men use guns to kill themselves because weapons are more apt to be fatal. Women are more inclined to overdose with oral medication, which makes them more likely to be rescued.

Alcohol or substance abuse plays a diminishing role in later-life suicides compared to suicides among youth.

Although older adults attempt suicide less often than those in other age groups, they have a high completion rate. For all ages combined, there is an estimated one suicide for every 100 to 200 attempts. Over the age of 65, there is one estimated suicide for every four attempted suicides, according to the American Association of Suicidology.

White men over age 85 were at the greatest risk of all age, gender and race groups. In 2012, the national suicide rate for these men was 47 per 100,000, more than twice the current rate for men of all ages.

The rate of suicide for women typically declines after age 60, after peaking from age 45 to 49. Women who become widows are more self-sustaining because of their background in taking care of the home, family and daily activities whereas men relied on the skills they used to work outside the home.

“This adds to their sense of loss of purpose because they are not particularly doing anything they feel is important,” Harr said.

Widowers are especially at high risk because older men, especially of the current generation, rely on their wives to create the social calendar and maintain social connections. When their wives die, the men cease to socially engage. Most men are not ready for retirement. They feel worthless once they stop working and are at a loss as to how to fill the hours. Some become closet consumers of alcohol.

“You don’t think of elderly people abusing alcohol, but they do,” said Coon. “It’s a depressant and increases impulsivity.”

Seniors at high risk of committing suicide have certain personality and behavioral traits that family members and caregivers might notice, including irritability, higher than normal dependency, feelings of helplessness as well as hopelessness, decreased ability to manage crisis and varying degrees of antisocial behavior.

The statistics and known risk factors are only a starting point, Conwell cautioned. One of the challenges is that there is not nearly enough known about the issue, which can be detrimental.

“The tendency is to speculate or oversimplify what, I’m quite sure, is a very complicated process,” Conwell said.

This article was first published January 13, 2012 by the Billings Gazette

Photo Credit: James Woodcock