Suicide survivor: 'There was a butcher knife in her chest. I just went berserk.'

Billings Gazette health reporter Cindy Uken is a 2012 National Health Journalism Fellow. This article is part of a series examining the suicide epidemic in Montana. Other stories in this series include:

Keep condolences to suicide survivor simple, such as, 'I'm sorry for your loss'

Suicide victims' loved ones often suffer guilt, thinking 'If only I had ...'

Suicide survivor: 'There was really no help for me and no hope'

Teenage girl fatally shoots herself days before '08 school year begins

Before a suicide, a mother's lament: 'Why can't I fix this?'

Miles City school administrators tackle problem of suicide

Play designed to help youth feel comfortable discussing suicide, feelings of despair

Suicide is 2nd leading cause of death among Montana youth

Veterans twice as likely to commit suicide as civilians

Police officer: 'Ma'am, I found your husband'

Veteran: 'I just always hoped that I would be in that freak car accident'

Suicide rate among Montana's senior citizens outpaces national figure

Veteran: 'You're taught in the military that you don't ask for help'

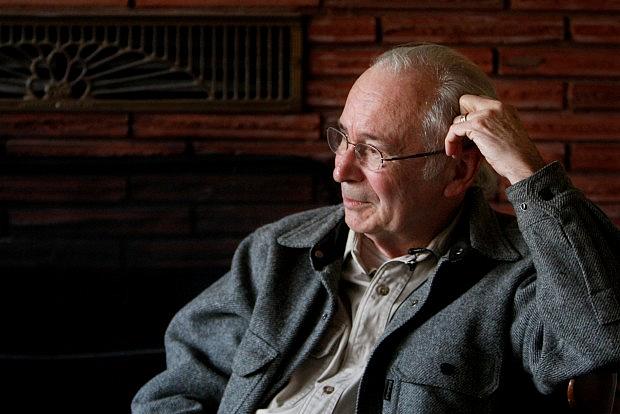

Paul Whiting, Kay Foster and Joan Nye are survivors of suicide.

Each has lived through the shock and horror of losing a loved one to suicide.

Each has experienced a sweeping range of emotions and reactions, including anger, relief and thinking, “If only I had ….”

For Whiting, it was his wife who took her own life. Foster and Nye each lost their sons to suicide.

None of the three survivors mentioned suicide in their respective loved ones’ obituaries.

Dorothy M. Whiting, 58, “departed from this earth, of an untimely death,” according to her obituary.

Foster’s son, Eugene “Geno” Walter Foster, 41, “left his body.”

John Vincent Meyer, 19, Nye’s son, “passed away.”

“One of the problems is that you can’t talk about it,” Whiting said. “That’s part of the stigma.”

Though different circumstances, each survivor had the same question: “Why?”

Cognitively, they know that 90 percent of people who kill themselves suffer from one or more psychiatric disorders, in particular major depression, bipolar depression, alcohol and drug abuse, schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress disorder, eating disorders and personality disorders.

Emotionally, they wrestle with the acts of their loved ones.

On April 12, 1997, Whiting left to teach a photography class at Montana State University Billings. He had called his wife, Dorothy, twice that morning to check on her. There was no answer. He surmised she had gone for a walk.

When he returned home, he scoured their Billings home, going from room to room looking for her, struck by the silence.

“I opened the door to the bathroom and there she was in the tub, half full of water, no clothes. There was a butcher knife in her chest,” Whiting said. “I just went crazy. I went berserk.”

There was no note.

He dialed 911.

Within minutes the couple’s home became a crime scene.

Police discovered a bunch of plastic bags in the bathroom where she died. Whiting suspects she tried to suffocate herself before stabbing herself.

In his whirlwind of shock and grief, Whiting, 75, would later learn he was a suspect in what authorities believed might have been a homicide.

“Why would I do a thing like that?” he asked. “It was preposterous.”

He and his pastor had to go to the police station that night. Eventually authorities were convinced his wife’s death was a suicide.

He blamed himself for his wife’s death and was convinced there was more he could have and should have done.

His wife had suffered from depression, was taking antidepressant prescription medication and was housed on two separate occasions in a local psychiatric center.

Whiting said he had “heard of depression” but was unaware of how serious it was.

“Like any marriage, it wasn’t perfect,” Whiting said. “Could I have been a better husband? I should have been kinder. I should have taken better care of her. I felt like it was all my fault because I wasn’t a good enough husband to her. I still feel that way.”

Angry that there was no local support group, he turned to a professional therapist. Today, nearly 16 years after his wife’s death, he still goes in for an occasional “tune up.”

In the absence of a formal support group at the time, he found solace in talking with four other survivors of suicide.

Some survivors take comfort in the goodbye notes their loved ones left behind. Whiting did not get that opportunity.

“It might have been easier without a note in some ways,” he said. “It’s just more stuff to torture yourself with.”

Whiting has since remarried. He and his wife, Betty, moved from the home where the incident occurred.

“It does get better,” he said. “Now it’s just a sadness. I miss the times we had.”

Foster knew her son, Geno, who had suffered from depression and drug and alcohol addiction, was spiraling downward. His father’s death, among other issues, was a trigger. His girlfriend had called Foster to let her know how bad things had gotten. She said he wasn’t going to work and was either drinking or taking some kind of drugs. There was nothing she could do.

So, Foster called her son to let him know she would be visiting him in Santa Monica. She wanted to get him into a rehabilitation program.

“Mom, next week would really be much better,” Geno told his mother. “Get your reservation and come next week.”

Foster complied with her son’s wishes.

Concerned, Foster, 71, called her son’s psychiatrist and pleaded for his help. Bound by patient confidentiality laws, the psychiatrist could tell her nothing.

Geno Foster hanged himself in his home the next day. It was Nov. 2, 2009.

Foster suspects he had it planned and that is why he asked her to postpone her trip to see him.

“It’s the worst thing that ever happens to you, losing your child,” Foster said. “It doesn’t matter how old they are. They are still your child. I felt really, really, really awful. And it doesn’t go away. You get through it.”

She, like so many other survivors of suicide, never dreamed her son would take his own life.

“That’s probably naive on my part,” Foster said. “He thought this was going to make everything better for everybody.”

She started attending a support group and remains a regular attendee today. She also sought the help of a psychologist. She, her husband and their daughter, who also suffers from depression, have participated in the Out of the Darkness Walks on both the community and national levels to benefit the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

Reaching out to others, and helping other survivors, has been her salvation, she said. Because those you are around all the time don’t want to hear about it anymore.

“If I would have been smarter, I would not have listened to him when he told me not to come and would have gone anyway,” Foster said. “But part of moving on is giving up on the what ifs.”

The last conversation Nye had with her son, John Vincent Meyer, was Friday, June 25, 1999. She thought he was on his way home from a meandering trip, though he kept his whereabouts secret. His dream of buying a home in southern Nevada didn’t work out. He was withdrawing from family and friends.

What Nye did not know was that he had sold his car for $50 and hopped aboard a bus with a gun he kept for protection. When he got off Saturday night in Mesquite, Nev., to spend the night, someone overheard a conversation in which Meyer reportedly said he was contemplating suicide. Police approached Meyer but he “snowed” them, saying he wasn’t serious. Still, they held his gun until he was ready to leave town.

On Sunday, he called his biological father, said he was not doing well and asked his father to take care of his affairs. He still would not say where he was. About 11 p.m. that night, authorities in Mesquite gave him a ride to the bus station and returned his gun. At 11:56 p.m., Meyer shot himself where the police dropped him.

Nye, 68, who believed her son was still wending his way home, received news of his death at 10 a.m. Monday.

“It takes your breath away,” she said.

Her son’s death was the culmination of five difficult years that included at least one suicide attempt.

“I could feel relief,” she said. “There was no way I would choose it but as his pain was over, our extreme fears, the emotions and the stress that were nonstop for five years were replaced by the horrendous, horrendous sadness of grief. “

He left a four-page note. It showed the mental illness and paranoia he suffered and revealed just how deep his depression and paranoia were. He felt like everything was closing in on him as though he were in a jungle, Nye said.

She described the first week as being wrapped in cotton batting. She was surrounded by friends and family. It’s the second week when the real surviving begins, she said.

“Every survivor of suicide loss feels guilty,” Nye said. “You know it’s not rational but you always ask yourself, 'Why didn’t I do this? Why did I say that? If only I’d done this.' That’s universal. You replay things in your head all the time. Gradually that lessens.”

She eventually channeled her grief into activism. Today, she chairs the Montana chapter of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. She also chairs a local support group for survivors of suicide. She, like Foster, has walked in national suicide-prevention walks and organizes the local Out of the Darkness walk.

“One never gets over the pain,” Nye said. “One never gets over the loss. But by doing these various things, and not just sitting silent in a shell, one moves along the journey of healing. It’s very slow, especially the first five years. Your mind is mush.”

This article was first published February 10, 2013 by the Billings Gazette

Photo Credit: Casey Page