Suit Challenges Ban on Paying Bone Marrow Donors

A father who lost his 11-year-old son to leukemia last year is one of five plaintiffs in a suit filed Feb. 15 in the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in Pasadena, Calif., challenging a federal ban on compensation for donors of bone marrow.

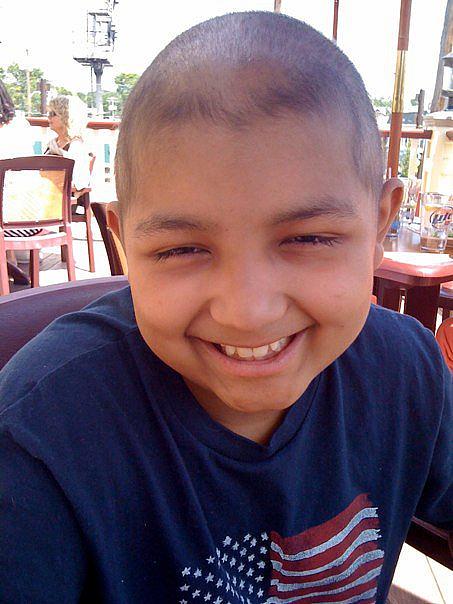

Biologist Kumud Majumder, currently a vice president for information technology at Citigroup, believes his son Arya would be alive today had a perfect bone marrow donor match been found for him.

“He would have survived,” Majumder told India-West, choking back tears at several points during a lengthy interview from his home.

The bone marrow donor pool is relatively small especially for minorities. Asian Americans have less than a 25 percent chance of finding a match.

Carol Gillespie, executive director of the Asian American Donor Program, likened the process to attempting to find an unrelated twin sister.

Three years ago, Kumud Majumder and his wife Swati found out that their only child had leukemia, after repeated visits to a pediatrician for a chronic, wheezing cough.

The initial pediatrician diagnosed pneumonia and put Arya on a course of steroids.

When their son’s condition worsened, despite the steroids, the Majumders insisted on x-rays and blood tests for Arya. An emergency room doctor at Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York finally diagnosed leukemia.

Arya spent his 8th birthday – July 29, 2007 – in the hospital. He died 33 months later.

The National Organ Transplant Act, passed by Congress in 1984, prohibits the sale of body organs, such as kidneys, but also bone marrow. Majumder believes the law is flawed, since donors of blood, plasma, sperm and ova – all replenishable like bone marrow – are allowed to be compensated for their donations.

Congress created the law shortly after the approval of cyclosporin, an immunosuppressant which for the first time allowed kidney transplants between unrelated donors.

“Congress did not want a kidney market,” said Bob McNamara, a staff attorney at the Institute for Justice which filed the suit last week. “But the law irrationally treats bone marrow as an organ, rather than renewable cells,” he told India-West, noting that this was the first suit ever to challenge the 1984 act.

More Marrow Donors, one of the plaintiffs in the suit, envisions a structure which compensates a donor with $3,000, in the form of an education or housing stipend or a donation to a chosen charity. Donors are simply being compensated for their time in the donation process, which can take 4-5 days in total, asserted McNamara.

Plasma and platelets, which are often bought from donors, are collected using the same apheresis technique employed in bone marrow collection.

Patients suffering from leukemia and other blood cancers typically undergo chemotherapy and sometimes radiation therapy to deplete all existing bone marrow, which serves as the body’s immune system.

After chemotherapy is finished, the patient receives a transplant of blood-forming stem cells — known as a peripheral blood stem cell transplant — to restore the bone marrow.

Bone marrow is typically restored within 30-45 days of receiving a stem cell transplant. Peripheral blood stem cell transplants have largely replaced bone marrow transplants, which involved sticking five needles into a hip bone to extract a donation.

Donors are matched for 10 markers on a human leukocyte antigen typing test. Matches are often difficult to find, especially among the South Asian community, because of the dearth of potential donors.

There has been a recent spike in the number of South Asian Americans needing bone marrow donations, Gillespie told India-West, noting that it was unclear whether the increased need was due to greater awareness or to other factors.

Gillespie, however, vociferously opposed the idea of compensating bone marrow donors. “It should be an altruistic donation,” she said, noting that an imbalance could be created between patients who could afford to pay for marrow donors and poorer patients.

“It’s totally wrong for someone to sell their bone marrow for money, and morally wrong for people with money to get the first choice of donors,” she said.

The Asian American Donor Program is operated by the National Marrow Donor Program. At any given time, more than 6,000 patients — primarily those with leukemia or lymphoma — are attempting to find a match.

Bone marrow registry drives are currently being held across the country to find a match for Sonia Rai, 24, and three-year-old Rayan, who currently has less than two weeks to find a match.

The suit will initially be considered by a panel of three judges, said McNamara, adding that if there is dissent, a panel of 18 judges would then take up the matter. He hoped that a decision would be announced by the end of the year.

Kumud Majumder has founded Arya’s Kids – www.aryaskids.org - a non-profit organization through which he hopes to raise awareness of pediatric cancer in much the way that the Susan G. Komen Foundation has raised awareness of breast cancer.

Asked to describe his son, Majumder cried briefly before saying, “If I was given the opportunity to describe an ideal child, I would not do better than him.”

Majumder recalled how Arya, while undergoing chemotherapy at nine, drew up a business plan for “Arya’s Diner.” He printed up menu cards, and would take breakfast orders from his parents in the night to have ready when they awakened the next morning.

Arya loved computers, sports and music, and towards the end of his life, began to write poetry, said his father, adding that what he remembered most about his son was a boundless supply of kindness.

“He had compassion beyond anyone’s imagination,” Majumder told India-West.