A Tiny Living Room Health Insurance Enrollment Center: A Model to Replicate?

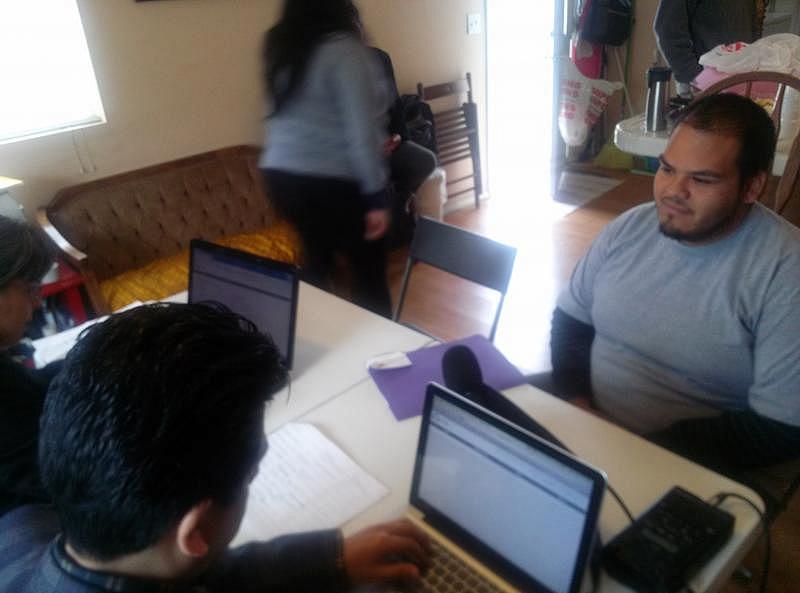

One Sunday morning, in the small living room of Ana Laura Villagrana’s modest house, two young people in their twenties consulted with a pair of certified Covered California assistants. Others were seated, waiting their turn. Meanwhile, Villagrana encouraged those who still had not come by telephone.

“We’ll see you here in a little while,” said Villagrana into the telephone.

Villagrana is 34 years old and works in a law library. Worried because the deadline to enroll for health insurance under the Affordable Care Act, March 31, is in a few weeks, she took the initiative, asked for the help of two certified enrollment assistants, and organized this health fair for her relatives and neighbors. Villagrana’s family members have low incomes, and most of them have never had health insurance.

“I told my family this event will be free, so they don’t have an excuse. We have already done the prescreening; we already have eight forms filled out. They are in the system just so they can come and have someone explain to them what they qualify for, and then they decide,” she explained.

Charity organizations and businesses like Blue Shield have tried similar focuses to promote enrollment in insurance programs in low-income neighborhoods. But until now, they have still not been able to considerably increase the number of Latinos that are signing up for insurance.

The Affordable Care Act created two new opportunities in California for low-income families to find health insurance.

The state created Covered California, an open exchange health market that offers a wide variety of insurance plans from private companies, including many at a low cost. The deadline to enroll in a Covered California plan is March 31. The state also started offering Medi-Cal, which is financed by federal Medicaid dollars, to more people. Enrollment for Medi-Cal is ongoing.

In Ana Laura’s house, the first person to finish the consultation was Augustín Martínez, 29 years old. He is Ana’s cousin. Augustín did not know, but he found out here that he qualifies for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), the Obama plan that benefits young undocumented people who grew up in the United States. These young people do not qualify for insurance offered under Covered California, but in California they do qualify for Medi-Cal.

Martínez was surprised that Medi-Cal was an option for him.

“I almost have it all now; I just need one paper about my income. I’ll send that to them by mail and this will be resolved for me in a few days,” he said.

It has been a year and a half since Martínez has seen a doctor. If he is insured, he knows the first thing he will do.

“I’ll go to the doctor so they can give me a physical, to check that everything is ok, because you never know,” said Martínez.

Ana Laura’s initiative, although it is on a small scale, is novel, precisely because so few Latinos in California have enrolled in Covered California. From October to December, only 18 percent of those who enrolled identified themselves as Latinos, a number that rose to 28 percent in February, according to Covered California employees.

Still, Latinos are not taking advantage of the insurance market as they had hoped. It is estimated that Latinos make up around half of the uninsured in California. Villagrana says that convincing her relatives and neighbors to enroll was difficult for her as well.

“I would dare say that it’s a cultural thing,” said Villagrana. “As a child, I remember that if I got sick, there were always home remedies first and the doctor was second, and it was only if in the case of emergency.”

One criticism that the Covered California agency has received is that it has not done enough to make personal contact with Latinos to enroll them. Santiago Lucero, a spokesperson for Covered California, said that they know that face-to-face contact is important.

“We, we have known from the beginning, that the Latino community has always preferred to enroll in person in their community, instead of on the Internet or by telephone,” he said.

Lucero pointed out that in the final weekends of the month, the agency will redouble its efforts to seek out Latinos outside of supermarkets, in libraries, and in schools. But he also recognized that the efforts of individual citizens like those of Villagrana are important, because the number of eligible Latinos without health insurance is still high.

“I tip my hat to Ana Laura, but I do want to stress that it is ok to help them, but this help has to be free,” said Lucero.

Through her small health fair, Villagrana managed to get five relatives and some neighbors to start the enrollment process. Before coming, her cousin Laurentino Doval, 24 years old, had decided it was better to pay the fine, but he changed his mind in Villagrana’s living room.

“I came because of family support,” said Doval. “My cousin did this for us in her house.”

Rosario Vigil, who hosts a radio program about health in Los Angeles, thinks that the idea of bringing Covered California counselors to the neighborhood, or to homes, like Villagrana did, is an excellent idea.

“People are skeptical. They want to see the face of the person who they are going to give such sensitive information to, like social security, income, how many dependents you have. When you have a counselor in front of you, it’s a different dynamic. It feels more like it is in confidence, and you have the right to ask questions, especially when it is in your language and especially when it is recommended to you by a person whom you trust,” said Vigil.

Vigil has verified this in her radio program with listeners, and says they have told her they have no desire to enroll by Internet or telephone.

“If this Obamacare approach in the neighborhood had been there since the beginning, we would have different numbers,” considered Vigil. “But we still have time. If we can replicate this same model in the time we have left, many Latino people can still be enrolled.”

Ana Laura’s passion for health insurance is because her family has a history of suffering from bladder and kidney stones. Eight years ago, Ana Laura ended up in the hospital because of strong gallbladder pain, but they only controlled the pain. She tried to buy insurance, but it was impossible for her.

“I went to Medi-Cal and I didn’t qualify because I didn’t have children. I applied for Kaiser and they denied me because I had a history of medical problems. The last option was an HMO, Blue Shield, and the same thing happened,” she said.

Villagrana spent 4 years enduring the pain. Finally, she got a job that offered health insurance. And through surgical intervention, she overcame her problem. Because of this, she has no doubt that being insured is important, and she seeks to make sure that her family and neighborhood are not left behind.

“It’s another type of life when you live without pain,” she said.