Uneven Ground: Part 1 - How unequal land use harms communities in southern San Mateo County

This story was produced as part of a larger project for the 2019 California Fellowship, a program of USC Annenberg's Center for Health Journalism.

Other stories in this series include:

The year was 1957, and two women, one white and one black, set out on an undercover investigation in Menlo Park and Palo Alto.

Their task was to investigate the hypothesis that real estate agents were conspiring to sell homes in certain neighborhoods to white people, and homes in certain other neighborhoods to black people.

They developed a plan that would ultimately prove their hypothesis all too correct: The black woman, who was not named in the study, would approach a real estate agent and express interest in purchasing a home in a predominantly white area. Then the white woman, researcher Elaine Johnson, would follow afterward, saying she was interested in buying a home in East Palo Alto or the Belle Haven neighborhood of Menlo Park, whose population had by then become predominantly black. Johnson would play naive, and record what she heard.

Over the course of 19 interviews the duo conducted (these included meetings with real estate agents in San Mateo, San Carlos, Redwood City and Los Altos as well, where similar interactions were reported), the agents nine times explicitly refused to sell the white researcher an East Palo Alto or Belle Haven home, said the area was not desirable, and stated that it was not desirable because the area had African American people living there.

While it’s easy to dismiss this history as a time when laws and attitudes were different, the impacts of these discriminatory actions persist in the health outcomes these neighborhoods experience today.

Research has shown neighborhood racial and ethnic segregation to be associated with adverse impacts on health in areas including cardiovascular risk factors, elevated rates of infectious disease, and premature death. Minorities in segregated communities are also more likely to have limited employment opportunities and lower incomes, as well as to face shortages of safe and affordable housing, all factors that affect health.

San Mateo County Health Officer Dr. Scott Morrow, the county’s top public health official, said the communities of North Fair Oaks, Belle Haven and East Palo Alto tend to light up as red flags on a number of indices when it comes to health problems because of bad health policy - linked with bad housing policy - compounded over generations.

In short, people with the lowest incomes are stuck in the least desirable and most polluted areas, he said. And now, the housing market is stretching those households to their breaking points.

This is borne out by The Almanac’s research: Of 76 people The Almanac interviewed in the neighborhoods of Belle Haven, East Palo Alto and North Fair Oaks, more than half identified the cost of housing as their top health concern.

Revealing research

Below is an excerpt of one of the 1957 interviews the two women conducted with a Menlo Park real estate agent, published as part of a collection of exhibits presented in hearings about housing held by the U.S. Civil Rights Commission in California in 1960.

It demonstrates that the agent and his colleagues clearly knew the laws regarding segregation and discrimination and flagrantly disregarded the intent of those laws to discourage community segregation.

The black woman reported that during her interview, she was treated well by the agent, who said he had lots of listings to show her.

Johnson, the white interviewer, got a more extensive response.

“Requested homes in my price range. Mentioned I had seen two homes I liked in the East Palo Alto area - one at 1140 Howard and one at 131 Hamilton. Realtor said, “I don’t like to say this, and I don’t want you to misunderstand, but we have a problem in that area.” I asked what the problem was and whether it was a low area in danger of flooding during heavy rains. He said, “No; it is a Negro problem. There is a very high percentage there.”

When I questioned how many, he replied, “About 52 percent of the children in the East Palo Alto schools are Negro.”

I told him I liked some of the homes there and asked if he could sell me one. He replied, “Yes, but I want you to be happy and I must be honest with you. ... Personally, I am a vet and have fought with Negro troops and I don’t mind them - but some people do, and property values drop when they enter a neighborhood.”

“What causes that?”

“Well, so many white families get scared and so many houses go on sale at one time that values drop.”

“Is it the entrance of the Negro family in the area that brings about this property devaluation, or that so many white families sell in panic?”

“Both; it is the fact that the Negro buys in a white neighborhood that causes the whites to worry and sell.”

She then mentioned a Palo Alto home she’d seen that had dropped $700 over the weekend.

The realtor said, “That is a sign they are getting scared, for they are so near the Negro area of East Palo Alto, which is just on the other side of Bay Shore. Here you don’t have to worry too much, for you have a fence on the west side, then Bay Shore Highway, then a high fence on the east side of the highway. This gives you a good barrier - at least a geographical barrier - to separate you from the colored area of East Palo Alto.”

He then gave me another listing in Palo Alto, and I asked if that was in a “restricted area.” He said, “Yes; it is on the west side of Bay Shore, and so far there has been no slopping over across Bay Shore, but there may be soon. So far the Negro people there have kept strictly within their lines.”

I asked, “How do you keep them in that area - draw a nice, tight little rope around the East Palo Alto area?”

The realtor answered, “No; one Negro family moves into an area; then others follow. Of course, we realtors have been accused by Nak-Kap of promoting segregated areas along the peninsula.”

I asked, “What is Nak-Kap?”

“That is the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Why, just today I had a Negro woman looking for homes in this area, but we don’t show them any property this side of Bay Shore.”

The realtor gave me another listing - this in Menlo Park. I asked whether it was in a “restricted area.”

He answered, “Of course, there is no restriction anymore because the Supreme Court says that we cannot restrict areas on the basis of color or creed any more. However, property owners can keep an area all white by banding together and agreeing to refuse to sell to orientals or Negroes.”

I agreed to return over the weekend with my husband.

This practice, called “blockbusting,” the researchers found to be widespread across the Peninsula. A real estate agent would try to scare white homeowners in a neighborhood into selling their home at a low price by telling them that black people were buying houses nearby, and then would go back and sell those houses at higher prices to black families, drawing upon white racial fears to gain profit and segregate the community.

Building on this research, a 1961 report by the U.S. Civil Rights Commission on housing found that “In the Palo Alto area ... only 3 of the 600 real estate brokers and salesmen show property on a nondiscriminatory basis.”

According to the commission report, many families in Belle Haven and the nearby Palo Alto Gardens, which were also subject to blockbusting, wished to buy homes in other neighborhoods, but were “blocked in their efforts by the concentrated efforts of peninsula realtors to keep them within these clearly defined areas east of Bayshore Highway.”

At the same time, the Federal Housing Administration and veterans Administration refused to insure mortgages for African Americans in designated white areas and did not insure mortgages for whites in neighborhoods where African Americans were present, according to Richard Rothstein’s 2017 book, “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of how our Government Segregated America.”

Rothstein reports that, amid a housing shortage in the area surrounding Stanford in the post-World War II years, Stanford professor and novelist Wallace Stegner joined and helped to lead a co-op, called the Peninsula Housing Association of Palo Alto, that purchased a 260-acre ranch near the university campus. The co-op made plans to develop 400 homes, a shopping area, a gas station, a restaurant and shared recreational facilities on commonly owned land.

But because three of the first 150 families to join the co-op were African American, the banks would not finance construction or issue mortgages to the co-op, following Federal Housing Administration policy. Unable to find funding, the co-op dissolved and in 1950, the land was sold to a developer who agreed not to sell any properties to African Americans. That area became Ladera.

Human Impact

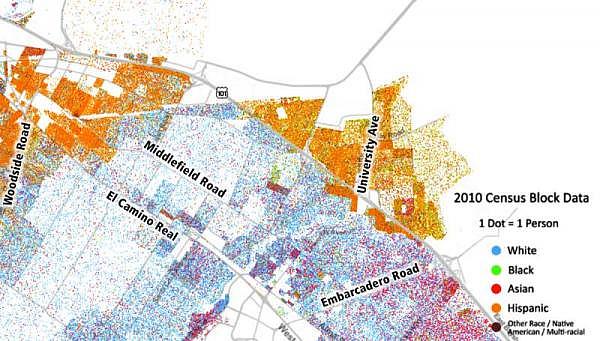

A map of the census tracts that bear the most significant environmental health risks, as measured by CalEnviroScreen 3.0, an index of environmental health, aligns strikingly with a dot map of where residents of color live in southern San Mateo County - specifically, in North Fair Oaks, Belle Haven and East Palo Alto. Despite being situated within one of the wealthiest areas in the U.S., these communities face substantially greater environmental threats like hazardous waste, impaired water, excessive traffic, housing burden, linguistic isolation, groundwater threats, poor education opportunities and asthma in their neighborhoods.

The racial dot map shows the population density and diversity in the U.S. based on 2010 census data. Each dot represents a person. (Map by the University of Virginia Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service.)

East Palo Alto reports that life expectancy in the city is 62 years, 13 years shorter than the San Mateo County average of 75. Children under 17 have the highest obesity rates in the county, and kids with asthma are hospitalized and taken in for emergency visits at nearly three times the county rate, according to the city.

On the Peninsula, these communities have historically, to varying degrees, not controlled their governance.

East Palo Alto became a city only in 1983, while Menlo Park’s Belle Haven neighborhood only now has its first City Council representative in three decades, after the city switched to having district elections last year in response to a lawsuit threat. North Fair Oaks, an unincorporated neighborhood nestled between Atherton and Redwood City, has an advisory community council, but is ultimately governed by the county Board of Supervisors. In the words of the community council’s chair, Ever Rodriguez, “Our councils are only advisory bodies. ...We are a dog without teeth. We can bark but we don’t bite.”

Pollution and Toxic Waste

A February 2018 study by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) published in the American Journal of Public Health reported that people of color are more likely to live near highways and be exposed to particulate matter that can cause and worsen health problems. Specifically, it found that black people are 1.54 times more likely to be environmentally burdened with exposure to tiny particulate matter of 2.5 micrometers or less, and other non-white people are 1.28 times more likely to bear this burden than their white counterparts.

According to the EPA, exposure to these small particles can, in the short-term, aggravate lung disease, cause asthma attacks and acute bronchitis, and increase susceptibility to respiratory infections; in the long term, it has been associated with reduced lung function, chronic bronchitis, and premature death.

But its guidance on how to avoid the particles is limited. In an informational brochure about the particles and their health impacts, the EPA advises people that they’re more likely to be affected by particles the more strenuous the activity and the longer one is outdoors. “If your activity involves prolonged or heavy exertion, reduce your activity time - or substitute another that involves less exertion. Go for a walk instead of a jog, for example.

“Plan outdoor activities for days when particle levels are lower. And don’t exercise near busy roads; particle levels are generally higher in these areas,” it advises.

It’s a tall order to ask someone to avoid exercise or spending time outdoors near a busy street when their neighborhood is surrounded by busy streets, or to perhaps exercise indoors in an area where reasonably priced gym access is a rarity in a sea of exclusive country clubs and private fitness studios.

That’s the situation Menlo Park Vice Mayor Cecilia Taylor says she faces as a Belle Haven resident. Belle Haven, a triangle-shaped neighborhood with a population of about 5,000, is bordered on all sides by “busy streets”: U.S. 101, Bayfront Expressway, and the ever-congested Willow Road. Taylor likes to exercise on the track at Kelly Park, she says, but only goes at certain times of the day because the air smells polluted during rush hour.

Belle Haven, she said, “was never designed for it to be a prosperous and healthy community. There’s no way to do that with the number of homes placed there, and the number of people.”

For many years, Belle Haven was the closest neighborhood to the city’s dump, now Bedwell Bayfront Park; many of the region’s dumps ringed the Bay.

And just across University Avenue along Bay Road in East Palo Alto, Romic Chemical Corporation began operations in 1964 and was a significant source of pollution in the community for many years. Later, community pressure and a series of environmental violations forced its shutdown in 2007.

The corporation had a decades-long history of leaking pollutants into the community. In 1995 it was cited for discharging cyanide into the sewer lines; there were fires there in 1989 and 1993; earlier that year a worker was injured when his safety equipment leaked while he was cleaning toxic residue out of a railroad tank car. In 1999, it was cited for failing to notify the Palo Alto Regional Water Quality Control Plant when it detected a compound in its wastewater discharge known to cause cancer. In 2005, the company agreed to pay $849,500 for violations between 1999 and 2004 such as storing waste in the wrong containers, according to the San Mateo County Times.

It wasn’t until May 2007 that the chemical recycling operation was ordered to shut down, following incidents in May 2004 and March 2006 when two employees were seriously burned, as well as in June 2006, when 4,000 gallons of solvents were released at the facility. Youth activists involved with East Palo Alto-based Youth United for Community Action are credited for their petitions, marches and rallies that pressured the operation to shut down.

As of February 2018, the site was still closed due to subsurface contamination, according to the California Department of Toxic Substances.

The Romic story made East Palo Alto a poster child for the environmental justice movement. Since then, the city has been taking steps toward those ideals to guard itself against more insidious threats, such as the frenzied Bayside growth of its neighbor, Menlo Park. While the development proposals in the works there are less likely to lead to toxic waste problems, and in fact will have to comply with rigorous green building standards, they threaten to exacerbate gentrification pressures on the community, which has seen a rapid decline of 6% - down to 11.3% - in its African American population between 2010 and 2017, according to census data.

In 2016, East Palo Alto filed a lawsuit against the city of Menlo Park and won a settlement that is likely to slow the glut of development projects proposed on the city’s Bay side. It requires developers that seek to build at the “bonus” level of density, or propose a master plan, such as Facebook’s “Willow Village” project, to conduct environmental impact analyses for the projects. Those analyses will have to look at traffic and housing impacts.

The Housing Crisis

As Morrow, the county health official, explains, the biggest health problem countywide today is the lack of affordable housing.

“That has become, in the last two or three years, by far the biggest problem that we have. ... It’s very frustrating. We don’t have the tools to deal with it.”

At the core of the housing crisis, he added, are the perverse incentives built into the tax structure that create the motivation for cities to support the construction of office space and not housing in cities.

“Until you fix the underlying policy, we can throw little things at this, but nothing’s going to fix that,” he said. “You can’t be healthy without a home.”

The pressures of high-cost housing, he said, are widening the wealth gap in the community. There are low-income folks who don’t have the resources to move, and the rich folks, but the people in the middle who can’t access subsidies and can’t pay for even substandard housing are “leaving in droves,” he asserted.

Increasingly, among those people in the middle are professionals like doctors and nurses, a fact that is affecting the department’s recruitment efforts.

“We don’t even pay our doctors enough to afford substandard housing,” he said.

The dearth of affordable housing throughout these communities hits low-income people especially hard and can harm their health in an “infinite number” of ways, Morrow added.

Dr. Rakhi Singh, medical director of the Fair Oaks Health Clinic in North Fair Oaks, explained a few of these impacts.

First, there’s the immediate risk of living in substandard housing conditions.

Some people can afford to rent rooms only in housing situations where they don’t have access to a refrigerator or kitchen, and so don’t have access to the tools to prepare nutritious food for themselves. (These are generally the more affordable, albeit uncomfortable, living situations advertised on Craigslist.)

Researchers at U.C. Berkeley’s Urban Displacement Project studied displacement in San Mateo County and found that when renters were displaced - whether by being formally evicted, harassed out by landlords, priced out by market forces or pushed out by poor housing conditions - their options were limited by market forces and exclusionary practices.

About one in three displaced households experienced homelessness or marginal housing within two years after being displaced. One-third left the county. These displaced people moved to neighborhoods with fewer job opportunities, worse environmental and safety challenges, and fewer health care resources, the report found.

Because affordable rent can be so hard to come by, people in these situations may also be hesitant to approach a landlord if there is a mold or pest problem. Mold can trigger asthma or allergies and pests can spread disease.

One Menlo Park woman was asked to move out of her apartment after she complained about cockroaches, the Berkeley report noted.

Others end up stuck in cramped housing conditions, which has been shown to negatively impact mental health and increase the risk of exposure to respiratory and other infectious diseases, according to the report.

Luisa Buada, CEO of the Ravenswood Family Health Center, said that while there’s been a consistent population of unhoused people who may also experience substance and mental health problems, the unhoused population has expanded substantially in the last three or four years to include people who are working or who lost their previous housing situation. RV living in particular, is on the rise.

A countywide count of homeless people conducted in January of this year reported a 127% increase in the number of people living in RVs since 2017.

Among patients who are unhoused and exposed to the elements, health challenges often reported are feet problems, bad circulation because people don’t have good places to sit or sleep, and abscesses and sores, she added.

More widespread and insidious are the ways that rent-related stress affects other aspects of well-being.

“There’s an enormous number of people who are housing-stressed and think they’re going to lose their house,” Morrow added.

This stress, Singh said, seriously hampers people’s ability to lead a full life.

Sometimes patients come in with a symptom like sleeplessness, Singh noted. After talking for a while, she added, the patient will reveal that he or she works two jobs to pay rent and has children and family members to care for.

Another patient might come in with lower back pain because he does heavy lifting all day. A doctor might prescribe rest, but he pushes back, saying he can’t take off more than a day for financial reasons. In the informal workforce, if people don’t work, they don’t get paid, she said.

These patients in particular have difficulty following through with longer-term health programs like physical therapy, she added, since they’re losing income every time they go.

Despite these stressors, 60 of the 76 residents of Belle Haven, East Palo Alto and North Fair Oaks The Almanac interviewed said they plan to stay in the community for the next five years, and 59 said they felt a sense of belonging in their community.

“I’ve lived here my whole life,” said East Palo Alto resident Gregoria Villarreal Diaz. “Where else would I go?”

Jesus Ruiz, also an East Palo Alto resident, said that even though he and his family sometimes live check to check and his household’s monthly rent has increased by $400 in the last three years, he’s been in the community for 23 years and considers himself a part of it. “We have jobs, family and friends here,” he said.

Given the urgency and broad health risks that housing challenges create for low-income locals in particular, health care professionals in San Mateo County are increasingly focused on helping people make lifestyle changes to boost their health, or “manage wellness” instead of treat diseases, Singh said.

This shift has prompted health providers including the Ravenswood clinic to try to address broader challenges in the community that affect health - termed the “social determinants of health” - defined by the World Health Organization as “the circumstances in which people are born, grow up, live, work and age, and the systems put in place to deal with illness.”

“The reason we exist while we call ourselves a medical home for patients – is essentially to reduce access barriers to care,” Buada said. “It all goes together. Our work is about health justice.”

About this story

This is the first of three stories in a series exploring the impacts of how land use affects health in the communities of North Fair Oaks, East Palo Alto and Belle Haven.

Kate Bradshaw reported this story as part of her University of Southern California Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2019 California Fellowship with engagement support from the Center’s interim engagement editor, Danielle Fox.

Three bilingual Sequoia High School students, Nataly Manzanero, Ashley Barraza and Mia Palacios, with the author, conducted more than 100 Spanish and English language interviews used in this report. Some of the photos are provided by middle school students who live in East Palo Alto and participated in a summer program of Girls to Women, an East Palo Alto nonprofit working to empower girls and women in the community. They were asked to take photographs responding to the questions: “What makes your community healthy? What makes it unhealthy?”

[This story was originally published by Palo Alto Online.]