What it takes for WA trans youth to access gender-affirming care

The story was originally published by the The Seattle Times with support from our 2023 National Fellowship.

Ashton Larkin applies a generous coat of liquid lipstick before his spotlight moment. His “gothic teenage queen” drag persona is Ember Royale.

Daniel Kim / The Seattle Times

Ashton Larkin was eagerly preparing for a particularly special birthday in late September. He was about to turn 18.

The milestone meant the Everett teen would become an adult. But it also marked another turning point: Larkin, who is a transgender man, would be old enough to move forward with medical care that affirms his gender identity without his mom’s permission.

In Washington, state law generally requires parental consent for most medical care for trans and gender diverse minors. There are also some types of surgeries youth normally can’t get until they turn 18, even with parent permission. In Larkin’s case, his mother has been one of his biggest sources of support, he said. But she preferred he wait on any medical changes until he became an adult.

He has waited almost six years, since coming out as trans in middle school.

“I don’t feel like a real person,” said Larkin, who started college at Lake Washington Institute of Technology in Kirkland this fall. “I feel like someone stuck in someone else, and I want to rip my skin apart to get to the other person.”

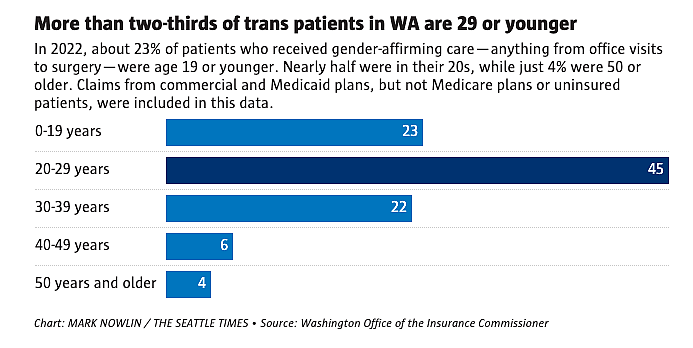

In Washington and throughout the U.S., medical and mental health providers say they’ve seen a recent surge in demand for care from young people whose gender identities don’t align with their sex assigned at birth. Trans youth often face a long journey, studded with hurdles, in questioning and exploring their gender identity — a journey that spans social, medical and mental health supports.

Some insurers won’t pay for gender-affirming care for patients under 18, for example. In recent years, the number of cases the state opened about gender care insurance disputes skyrocketed, from three in 2015 to over 120 in 2022.

I feel like someone stuck in someone else

— Ashton Larkin, 18

There’s the ongoing political debate, which is emotionally exhausting for many in the queer and trans community, but particularly kids and teens. This year, lawmakers across the country introduced more than 500 anti-LGBTQ+ bills, including in nearby Idaho, that target access to health care, bathrooms and youth sports, among others.

To many LGBTQ+ families, Washington remains a haven where this care is legal. But that’s led to its own challenges: More people are seeking services here, overwhelming a system that’s already underequipped, said Matt Goldenberg, a psychologist at Seattle Children’s popular gender clinic.

Youth can face monthslong waits just to get an initial appointment at the Children’s clinic, he said.

“Young people have to be willing to show faith and confidence in a system that has failed them,” Goldenberg said. “That itself can be a barrier.”

Goldenberg and other LGBTQ+ advocates also work to increase young people’s chances of finding safety and community along the way. Efforts have blossomed into pockets of positive social spaces throughout Washington — including community centers, school clubs and online groups.

On this night in Snohomish County, drag performers take an intermission outside the bar. After a costume change, Ashton Larkin talks with his mom and a close friend. Larkin’s 18th birthday marks a turning point: he’s now old enough to move forward with gender affirming medical care without parental permission.

Daniel Kim / The Seattle Times

Within the past year, Larkin has embraced a home within Snohomish County’s drag community, exploring different facets of gender through his drag queen persona, Ember Royale.

But Larkin still struggles with anxiety and depression. He can’t wait to start his own medical transition, he said.

LGBTQ+ youth are at a significantly increased risk for suicide, depression and anxiety, in part because of stigmatization and mistreatment, research shows. The Trevor Project found in its 2023 mental health survey that nearly 1 in 5 trans and nonbinary youth had attempted suicide in the past year.

“Gender-affirming care is suicide prevention for trans kids,” Larkin said.

Planned Parenthood pins are free for the taking at a fall clothing swap at the Rainbow Center in Tacoma. The clothing swap serves as an uplifting opportunity for trans and queer community members to pull together gender-affirming outfits.

Daniel Kim / The Seattle Times

What is gender-affirming care?

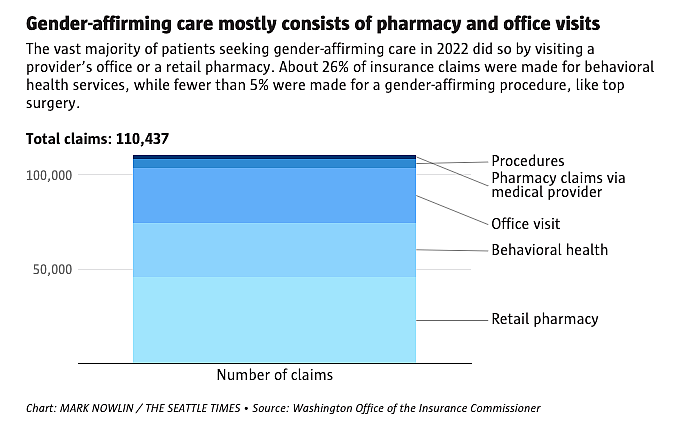

Gender-affirming care is a term often shrouded in confusion and misinformation, providers say.

Although it’s sometimes thought of as solely medical or surgical interventions for trans people, providers say it’s much more expansive — and isn’t necessarily only for those who identify as trans, nonbinary or gender diverse.

Gender-affirming care includes any care that helps someone feel supported in their gender identity. Some researchers say cisgender people, or those whose gender identity matches their sex assigned at birth, actually seek these types of services most often — including breast reductions, birth control, hair transplants and testosterone supplements. Yet trans patients face disproportionate stigma and barriers to access, providers say.

For gender-diverse patients, this care can help address symptoms of gender dysphoria — a state of distress or discomfort at a disconnect between someone’s gender identity and their sex assigned at birth.

A specialty that goes beyond medicine and surgery, gender-affirming care can also include name and pronoun changes; affirming clothing, makeup and haircuts; and safe, celebratory community spaces, according to local providers and LGBTQ+ community centers.

“[Social supports] are really incredibly helpful tools for allowing youth to explore their identity and explore what feels good without any medical treatment,” said Charlie Best, former education manager at the Rainbow Center, an LGBTQ+ advocacy and education organization in Tacoma.

Mental health support is also a growing part of gender care resources for kids and teens — and an often complex field to navigate for the state’s youth therapists and psychologists.

In clinical spaces, minors can get prescriptions for puberty blockers, which pause pubertal development, or hormone treatments, like testosterone or estrogen, which can be administered by injection, pill or patch. Parent permission is required for both.

Every patient is different, but most research recommends youth who require gender-affirming medical treatment begin talking with a doctor once they start nearing puberty, said Dr. Kevin Hatfield, a family medicine doctor at The Polyclinic who has provided care for gender diverse patients in Washington since 2005.

There’s no one way to be trans.

— M, 15

Some might be ready to start taking hormones as they progress through adolescence — while for other young people, hormone changes and surgical interventions aren’t appropriate, Hatfield said.

Gender-affirming surgeries are much less common than mental health and medical, nonsurgical support among Washingtonians under 18. Minors can receive what are known as top surgeries, including mastectomies and breast augmentations, with their parent’s permission.

Providers in the U.S. generally do not perform any face surgeries or bottom surgeries (genital reconstructive procedures) for those under 18, even with parent consent.

Chart: MARK NOWLIN / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Source: Washington Office of the Insurance Commissioner

For M, a Puyallup teen whose family requested they be identified by their first initial to protect their safety, things like gender-affirming haircuts and clothing are among the most important supports to help them feel good about their gender identity and how they express it.

They take period suppressants to stop menstruation, and currently don’t feel the need to pursue surgery. But they know others who are gender diverse might want to.

“There’s no one way to be trans,” the 15-year-old said.

M, a ninth grader, gets braids at a Puyallup hair salon last month.

Daniel Kim / The Seattle Times

An evolving field

When the Seattle Children’s gender clinic opened in 2016, it was the first pediatric hospital in the state with a dedicated clinic for gender-related medical and mental health services, though some Washington doctors had been offering the care for years.

At the time, the clinic staffed three medical providers. Now, it’s one of the largest gender clinics in the country with more than 10, including endocrinologists, psychiatrists, social workers, adolescent medicine specialists and mental health professionals. The hospital also staffs plastic and reconstructive surgeons, who provide some gender-related surgeries, said Dr. Juanita Hodax, clinic co-director and a pediatric endocrinologist.

Even as the staff tripled, patient demand has kept up. Children’s declined multiple requests to share data on how many patients the clinic sees annually, but waiting “a few months” for an initial appointment is not uncommon, Hodax said.

At Mary Bridge Children’s Hospital in Tacoma, owned by MultiCare, the number of patients seeking gender-affirming care has grown more than 1,100% in the past eight years, from about 59 in 2015 to 730 last year, according to a hospital spokesperson.

Demand is rising, Hatfield at The Polyclinic said. But, he added, “I don’t think the actual numbers of kids on the gender journey, as I would say, are truly increasing.” Because it’s become more socially acceptable to explore feelings around gender, among other possible explanations, he said, reports have suggested that in recent years more people have felt safe openly identifying as LGBTQ+.

Chart: MARK NOWLIN / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Source: Washington Office of the Insurance Commissioner

Despite the need, the number of providers trained in working with gender diverse youth has not risen at the same pace, he said.

Even within health care facilities that offer gender-affirming services, the scope can be limited. The Polyclinic doesn’t offer mental health support, Hatfield said, while Mary Bridge doesn’t provide any gender-affirming surgeries. Sacred Heart Children’s Hospital in Spokane offers mental health counseling, but no gender-affirming procedures or hormone treatment for minors.

At the same time, ever-changing guidelines around best practices can be intimidating to wade into — or too political — and can discourage more providers from diving into the field and seeking more education around the topic, said Megan Wagoner, a queer-affirming psychologist in Seattle and co-president of the Washington State Psychological Association.

The World Professional Association of Transgender Health acts as a guiding light for many gender care providers, offering a 250-page document outlining standards of care. But even there, gray areas exist.

While current standards guide providers on how to answer younger patients’ questions around gender, they don’t specify a minimum age to begin gender-affirming medical or surgical treatment — meaning providers must largely decide what to recommend, and when, on a case-by-case basis.

Other medical organizations also have evolving recommendations: The global Endocrine Society used to advise deferring all gender-affirming surgeries until at least age 18, but in 2017 changed its language to recommend only deferring bottom surgeries.

Debate around gender care practices is also active among mental health providers, who are usually required by insurers to submit an approval letter before surgeries and other medical care for gender diverse youth. Providers with little or no training in gender-affirming care are sometimes unsure how to approach those conversations, Wagoner said.

When Larkin tried to bring up his gender dysphoria in therapy several years ago, his therapist “did not know what to do,” he said.

“If you are not trained in that field, or you haven’t been through it, people don’t understand unless you really slow it down,” the Everett teen said.

At The Polyclinic, Hatfield often starts patient conversations the same way: “Tell me the first time you realized your feeling of gender was different from what other people were putting on you.”

Some kids, especially younger ones, might not yet have the ability to verbally express their feelings. But others do, he said.

Children’s gender clinic providers also cover a lot in the first few visits: health history, social life, academics, experience with self-harm, disordered eating, substance use, and gender goals, among other topics.

WPATH recommends that mental health providers only green-light medical or surgical treatment for a young person if they’ve experienced gender dysphoria for a long period of time; guidelines recommend “several years” for most, but also acknowledge that might not always be “practical nor necessary.” Still, many providers say they also don’t want to further delay care for their patients, when there are already obstacles for young people.

In Washington, “the process is already so slow that the idea of, ‘Wait a minute, we’re moving too fast’ — I just have not seen any evidence that that’s happening,” Wagoner said.

Last year, a study from the University of Washington found evidence gender-affirming hormones and puberty blockers can significantly help reduce depression and suicide risk in trans and nonbinary youth. According to the report, those who received hormones or blockers were 60% less likely to experience depression and 73% less likely to experience self-harm than those who didn’t.

“Sometimes medical management is really the way to keep the patient the safest,” Hatfield said.

With parent permission, minors can get prescriptions for puberty blockers, which pause pubertal development, or hormone treatments, like testosterone or estrogen. They can be administered by injection, pill, patch or cream.

Daniel Kim / The Seattle Times

Denials of care

Even when doctors determine gender care is medically necessary for minors, insurance restrictions sometimes block access.

Pax Enstad was 16 when he traveled with his family from their home in Bellingham to San Francisco to get top surgery, partially due to insurance issues and limited providers here. PeaceHealth, which covered his family’s health insurance, cited a transgender exclusion in its policy. Enstad’s mother said she was told the surgery was “cosmetic,” not medically necessary — despite approval from his doctor.

Enstad remembers it seemed he’d have to wait for surgery until he turned 18. His family, with help from the ACLU, filed a lawsuit against the hospital.

“I just thought, ‘Oh my God, I can’t,’” said Enstad, who is now 23 and has a degree in painting. “That’s the best way I can describe it: ‘I don’t know what I’m going to do if I have to wait.’”

To him, surgery was “way more important” than hormone medication, he said.

“Not everyone wants to be on hormones,” Enstad added. “Dysphoria feels different to everyone and my dysphoria was way more focused on my chest than anything that comes with hormones.”

Two years later, PeaceHealth changed its policies to explicitly cover surgeries for those over 18. By the time the lawsuit settled, Enstad had already moved forward with top surgery, which his family funded by getting a second mortgage and dipping into his college funds. He couldn’t wait. He knows many aren’t able to do the same.

“I just felt like my body didn’t belong to me before that,” Enstad said. After, “I just felt very free.”

Insurance denials are not uncommon if a patient’s plan is not regulated by the state or if an insurer is based in a state with gender-affirming care bans — even if the patient lives in Washington, said Dr. Shane Morrison, a gender-affirming care surgeon at Children’s.

Dysphoria feels different to everyone.

— Pax Enstad, 23

The state passed legislation in 2021 that requires insurance companies to cover medically necessary gender-affirming care, regardless of age, but insurers sometimes argue that gender-affirming care for minors isn’t medically necessary, he added.

The state Office of the Insurance Commissioner has opened more than 370 cases since 2015 involving complaints or questions about gender-affirming care for both youth and adults — about 69% of which involve coverage denials or claims handling, according to data shared with The Seattle Times.

“I fear (and am certain) that when he learns of this denial, he will backslide into severe mental health issues, he will lose motivation in school, and in life in general,” one parent wrote in a complaint to the OIC after receiving a denial from Blue Cross Blue Shield.

OIC told the family their insurance plan fell outside the state’s jurisdiction.

Earlier this year, a trans King County teen and his family filed a class-action lawsuit against Mountlake Terrace-based Premera Blue Cross, alleging the insurer repeatedly denied coverage of his medically necessary top surgery.

Premera has pushed back against the complaint, saying it has age limitations for many surgeries, not just gender-affirming ones.

“Our medical policy for gender-affirming services has been thoroughly researched and is based on the most current scientifically sound clinical evidence,” Premera spokesperson Amanda Lansford said in a statement at the time. The insurer declined to share copies of clinical evidence referenced.

“There is no science that says this is not appropriate for someone who has met all the WPATH requirements, as this young person has,” Ele Hamburger, one of the attorneys representing the teen and his family, said when the suit was filed in July.

LGBTQ+ affirming children’s books are available to read at the Rainbow Center.

Daniel Kim / The Seattle Times

Political minefield

While a lack of providers and insurance battles can delay care in Washington, many LGBTQ+ families consider the state a safer refuge than other parts of the country. This year, more than 20 states approved bans on medical and surgical care for trans youth.

The political debate — often promoting anti-trans messages and misinformation — is hard for many gender diverse youth and their families here to ignore.

“My sister lives in Idaho, and I’m scared to visit with my kids,” said M’s mom, in Puyallup. In January, it will become illegal for Idaho minors to access gender-affirming medical or surgical care, per a bill the state’s governor approved this spring.

MaKael White, a relational art therapist in Pierce County who works with many LGBTQ+ youth, has seen the stress and anxiety these policies cause.

“Isolation is the single biggest killer in the LGBTQ community,” said White, who works at Hope Development Practice, a group of therapists focused on care for rural and LGBTQ+ communities. “It doesn’t take much to be able to see how kiddos feel like no one cares about them.”

In Washington, providers say they have already noticed more out-of-state patients seeking gender-affirming care, though the state doesn’t track these numbers. Gender clinic staffers at Seattle Children’s anticipate a bump once more bans go into effect.

“It’s sort of the only option for people to seek care — to be able to get it out of state,” said Hodax. “I think it’s going to be really hard to have all of these increasing patients from other states.”

The state’s LGBTQ+ community and access to resources came as a relief to nonbinary 12-year-old Ollie when their family moved to Joint Base Lewis-McChord two years ago.

The Pacific Northwest has felt much safer than past homes, including those in Georgia and Tennessee, said Ollie’s mom, Krystal Jimenez. Washington lawmakers this year enacted a “shield law” to protect out-of-state families seeking gender-affirming care here.

“Trans people are targeted overwhelmingly,” said Ollie, who came out as trans at age 8. “I’m learning I’m different. And I’m learning to embrace that.”

Ollie has found community in art — they like digital art, poetry, writing, drawing, acting and singing.

A poem they wrote this year was titled, “They Want to Make Me Illegal.”

I’m a trans child who lives in the U.S.

In the land of the free, home of the brave

But politicians out here tell me how to live and behave?

Ashton Larkin, center, strikes a pose during his recent 18th birthday celebration drag show. Larkin came out as trans more than five years ago. He loves how drag has provided a supportive community.

Daniel Kim / The Seattle Times

A special milestone

The week after his 18th birthday, Larkin burst into the dressing room of an Arlington bar and restaurant where he frequently performs. He donned a red dress, striped tights, white boots and a purple wig.

He didn’t always feel comfortable expressing his feminine side after he came out in middle school, worried people would think he wasn’t a “real” trans man if he did. But drag has been healing for him and taught him to reclaim that part of his identity.

That night’s show, an ode to the new adult, was filled with pop-punk performances and an onstage “Happy Birthday” serenade.

Now that he’s 18, his mom feels more comfortable moving forward with treatment. Larkin has always understood her concerns, knowing why she wanted him to be sure about transitioning before starting hard-to-find and often expensive medical care. He’s also always been sure.

Ashton Larkin, 18, basks in the spotlight during his first solo of the night.

Daniel Kim / The Seattle Times

Larkin is still searching for a gender care provider who takes his insurance, but hopes to start hormone therapy soon, with surgery consultations to follow.

“Sometimes I wish I could have waited until I was 18 to come out,” he said. “But I know now I could not have waited.”

For many, accessing gender-affirming care can feel like pulling a slot machine and hoping for all three matches, said Goldenberg at Children’s.

“You need your insurance to pay for the service. You need a provider that takes that insurance. And you need the clinic that will actually see you as a trans or queer person,” he said. “All of those three things have to line up for someone to have anywhere near an equitable health care experience.”

Correction: This story has been updated to correct the percentage increase in patients seeking gender-affirming care at Mary Bridge Children’s Hospital. The number grew more than 1,100% since 2015.