How I used engagement journalism to report on local air pollution

(Photo: San Luis Opisbo Tribune)

Sitting in a living room in a neighborhood with the worst air quality in this region of the California Central Coast, a woman told me her adult daughter had a constant cough since moving back home.

She said she couldn’t keep the house clean, everything was always covered in dust inside and out. She had read my stories about the dust from the dunes in the local newspaper, The Tribune, and I asked if she thought her daughter’s persistent cough might have something to do with dust that blows in on windy days.

She hadn’t considered that. “When I read news about the dunes, I scan the story looking for the sentence that says whether it is dangerous to live here, and I never find it,” she told me.

That’s when I realized I needed to write stories for the community instead of about the community. It is my job to provide the public with information they need to answer their questions and understand their risks.

For a few years I’d been writing about the plume of dust that blows from the off-highway vehicle park on the Oceano Dunes, creating high levels of particulate matter that can harm respiratory and cardiovascular systems.

Most of my work focused on the regulatory or political fight, as local air quality regulators and State Parks have been in a long legal and political standoff. The coverage left a lot of community members unaware that the dust could cause asthma in their children.

Using engagement journalism strategies with the Center for Health Journalism, I set out to flip my reporting process and start by listening to community questions and concerns.

I wanted to move the public conversation forward and better serve our community by investigating the health effects of the politicized issue. No local health study had been done, so it was easy for critics to dismiss the risk.

I had three overarching questions:

- What are the levels of particulate matter on the Nipomo Mesa, the community just downwind from the dunes?

- What are the known health risks of exposure to those levels of particulate matter?

- What are the health experiences of residents?

I dug into data from public air quality monitor databases and decades of annual reports of the county Air Pollution Control District, identified trends and compared my notes with analysts.

I interviewed local doctors and national experts, read research findings, and elbowed my way into a conference on air quality to better understand the known risks of exposure to the levels of particulate matter on the Mesa.

And from March to September I heard from more than 300 community members about their health experiences, hosted an event for residents to ask questions of local doctors, and distributed information about how residents could protect themselves.

To investigate the topic more thoroughly, I worked with Danielle Fox, the engagement editor at the Center for Health Journalism, to learn about and practice engagement journalism.

The approach invites community members most impacted by an issue into the reporting process. It’s about building more meaningful and reciprocal relationships with your readers and the broader community.

The results were measurable. The project led to a shift in public understanding about the health risk, helped improve the health of several residents, and helped spur policy change.

Local air pollution stories are waiting to be told

Thousands of stories about local air pollution go unreported, and now is a good time to investigate and publish them.

Air quality in the United States has generally improved since the Clean Air Act was passed and then strengthened 50 years ago. But the trend fails to hold up in towns and cities where local pollution hot spots harm public health. These are often traditionally marginalized communities, especially in California.

Efforts to reduce pollution and improve public health are often delayed by a combination of pressures: polluters' influence over regulatory bodies, lack of political will, and misinformation made worse by a lack of local health studies. Meanwhile, air quality standards have not kept up with science, and the federal government is weakening regulations.

Journalism can help — especially journalism that combines local air quality data with science reporting and community engagement. Thanks to new consumer air quality monitors on the market, it’s easier than ever to investigate local conditions.

With shelter-at-home orders to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, several communities have seen what clearer skies and less air pollution can mean for their health and quality of life.

Lessons, tips and tools from the field

Here’s what I found while investigating air quality:

● The National Air Quality Index poorly conveys the risk of air quality levels. When air quality is categorized as “unhealthy for sensitive groups,” that means there is a health risk to children under 18, adults with heart or lung conditions, and all adults over 65.

● Historical data from local air quality monitors throughout California is available in some areas. If pollution is from a stationary source, wind direction and other meteorological data from the same monitors can help pinpoint the origin.

● Air pollution levels at a community- or neighborhood-level are often unknown because of a lack of monitors. Reporters can supplement government information with crowdsourced data from consumer monitors. We can also deploy our own monitors or view data from public consumer monitors online.

● Different brands of monitors on the market are better at registering certain kinds of pollution. AirVisual monitors are more user-friendly and better capture dust emissions. PurpleAir monitors are cheaper and better at registering wildfire smoke.

Here are five engagement strategies that worked for me:

1) Go to the community and listen.

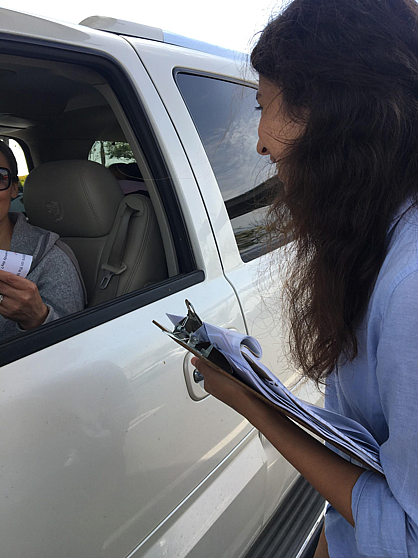

People living with poor air quality are experts on their experience. Early on, we met with the most involved community members and heard their feedback on our project. We went door-to-door in areas with the worst air. And we listened to parents and guardians in pick-up lines outside a neighborhood school.

If a community is hard to reach, try harder to reach them. That might mean partnering with an organization that already has relationships in the target community. If might mean going to food pick-up lines, putting up fliers or leaving notes on front doors.

2) Ask for help with your investigation

Using what we learned from our initial outreach, we put a call out for residents to help our investigation, through an online survey using Google Forms. We embedded it in our stories, circulated it in local Facebook groups and on Nextdoor pages, and we asked community leaders, city council members and county supervisors to share it.

In the survey, we asked if anyone in the household had lung or heart disease, asthma or a frequent cough. We asked what respondents thought might be causing the problem and whether they had seen the plume of dust. We asked how to better reach out to the community to listen to more people. And we asked what questions they had for us.

3) Collect your own data

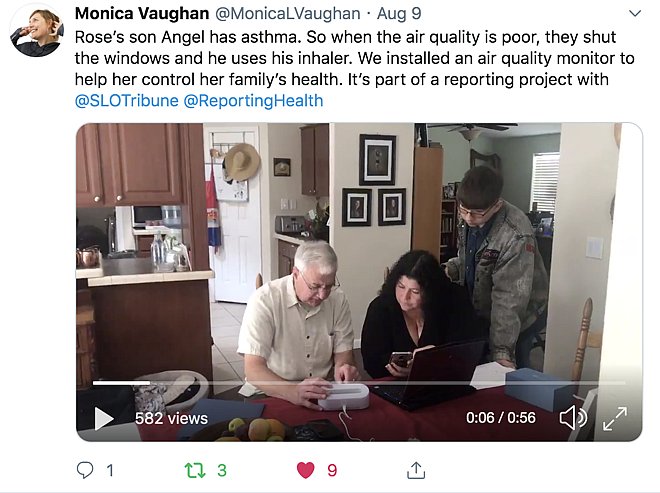

We distributed air quality monitors to three families managing asthma in neighborhoods that didn’t have public monitors. We found these families because they responded to our survey, and we asked them to keep track of their symptoms and compare them to readings on the monitor.

A community member who had expertise in air quality monitors volunteered to help install and maintain the equipment we purchased with grant funds from the Center for Health Journalism.

4) Bring information to the community

Answering community questions and responding to feedback went beyond publishing stories. We organized an event where residents could ask a panel of doctors and public health officials about the risk and how best to protect themselves. We provided Spanish-language interpretation, childcare and snacks, and had a resource fair with nonprofits and health providers.

We distributed fliers during after-school pick up and posted them on school and local business bulletin boards. We gave presentations at library family reading hour, and promoted the event by partnering with local air quality and public health officials, clean air advocates, and San Luis Obispo County’s Promotores, a group of Latina health educators. We got coverage from public radio, the alternative weekly paper, TV news and Telemundo.

At the time off-road vehicle enthusiasts questioned whether the health risk was real, implying that the issue was made up as leverage to shut down the park. Some showed up to the event with the intent to protest.

We established community guidelines early in the event to focus the conversation on health. Then we acknowledged everyone in the room, from off-roaders passionate about keeping their park open, to parents worried about their children's health. Everyone remained civil and had their questions answered.

5) Continue the conversation

At the end of several stories we included a form that asked for people’s response and questions. Their feedback led to follow-up reporting, including Q & A stories and videos with advice on how to best protect health on bad air days. Throughout the project, I kept members of the community updated by sharing my stories and additional information through an email blast, and by returning a lot of phone calls.

Ultimately, the relationship between the community and The Tribune was strengthened because of this project. And because we were in close communication with our sources, readers, and the broader public, we were able to learn more about the impact of our work.

Our stories were published before an important hearing on air quality, part of the fight by the Air Pollution Control District against state inaction. In previous hearings, a mid-level director had represented the state. Soon after our stories were published, the top director of State Parks appeared at the hearing and agreed to terms that would immediately begin the work of reducing dust emissions.

We also learned of measurable improvements in residents’ ability to manage their own health. For example, the number of people receiving air quality alerts so they could protect themselves on bad air days increased by 50% directly following our event. And some childrens’ health improved because of our education efforts.

Six-year-old Kagan sometimes coughed so hard hard at night he threw up. He was undergoing treatment and tests for allergies when his dad saw a flier for our event. Both he and his wife were able to attend because we offered childcare.

There they learned from a local pediatrician that asthma is frequently misdiagnosed as allergies. A few weeks later, Kagan’s mom told me they went to the doctor. Kagan was diagnosed with asthma, is on different medication, “and is doing so much better.”

Overcoming obstacles

Reporting on complicated health and policy issues, particularly on politically sensitive issues, will always come with challenges. Here are big obstacles I faced and how I overcame them.

Problem: Lack of scientific research on exposure to air pollution. Most research on the health effects of particulate matter analyzes long-term exposure at a population level. There are limited findings on the risks of short-term or repeated exposure.

Work around: Show your data to experts and ask what the risks are to air pollution at those levels. Write about the general risks of exposure to bad air. For example, we know that bad air can take years off a community’s average life expectancy, whether the source is a factory, mining, cars and trucks, wildfires or something else. Air pollution caused 8.8 million premature deaths worldwide in 2015, recent research found, and damage to health goes beyond the lungs and heart.

Still, it’s important to never exaggerate health effects or make comparisons without checking with experts. And remember that a health risk means it could happen, not that it will happen.

Problem: Residents don’t want to engage in a controversial issue.

Solution: Focus on the air quality levels and health risks, not the pollution source, when first reaching out to the community.

Problem: Haters.

Solution: Draw strong personal boundaries about when to engage.

Problem: Lack of community trust.

Solution: Work with core members of the community first. Inviting community leaders to come to the newsroom for meetings is a signal they are important.

Danielle Fox, engagement editor with the Center for Health Journalism, contributed to this post.

Read Monica Vaughan's fellowship story here.