Reporting on Mental Health Cuts and their Consequences

In all the years I’ve worked as a reporter covering social issues, I’ve been particularly intrigued by the funding problems in California’s mental health system. While reporting a series on access to primary health care in the Central Valley in 2011, I heard over and over from local health officials– and advocates around the state – that, in recent years, cuts had taken a particularly severe toll on mental health services.

I had been struck by a comment made to me by Rusty Selix, one of the co-authors of the 2004 Mental Health Services Act, also known as prop 63, a ballot measure that levied a one percent tax on millionaires to fund innovative programs for the state’s mentally ill. Selix had told me he thought access to mental health care was actually worse than it had been before the Act was passed.

I was left with questions: Why does mental health seem to get hit so much harder by cuts than other arenas? What do these cuts look like on the ground? How have they impacted people with mental illnesses, their families, and society at large?

How the story evolved

To answer these questions, I proposed to go back to Stanislaus County – where we did the original series on access to health care – to do a series on access to mental health care. Lauren M. Whaley, the Center for Health Reporting’s photographer, radio, multimedia person, offered to join me.

After much research, Stanislaus County seemed to be a good place to focus because it had been hit particularly hard by the economic downturn and, for a variety of reasons, by the cuts to mental health services.

In four years, the county department of Behavioral Health and Recovery Services, which oversees mental health services, had lost more than 200 positions – some 37 percent of its staff. In 2003-4, the department served nearly 13,000 county residents. By 2011, that number had dropped closer to 9,000.

Between 2007 and 2009, one local ER saw an increase in the number of patients with a psychotic diagnosis, from 276 to 681.

At the same time, in the past six years, the numbers of mentally ill inmates in the Stanislaus County jail had increased nearly 50 percent.

What it ended up being about

Although I knew I had to tackle the policy issues surrounding the mental health cuts, I always wanted to make this a very human story.

We began visiting and interviewing as many people touched by the cuts as possible. Lauren and I spent lots of time at the offices of the local chapter of NAMI, the National Alliance on Mental Illness, as well as doctor’s offices, support group meetings and people’s homes. We went on police ride alongs, attended court hearings, and toured the mental health unit of the jail. I looked for places in the community that illustrated the lack of services – and also gave me good access to compelling subjects.

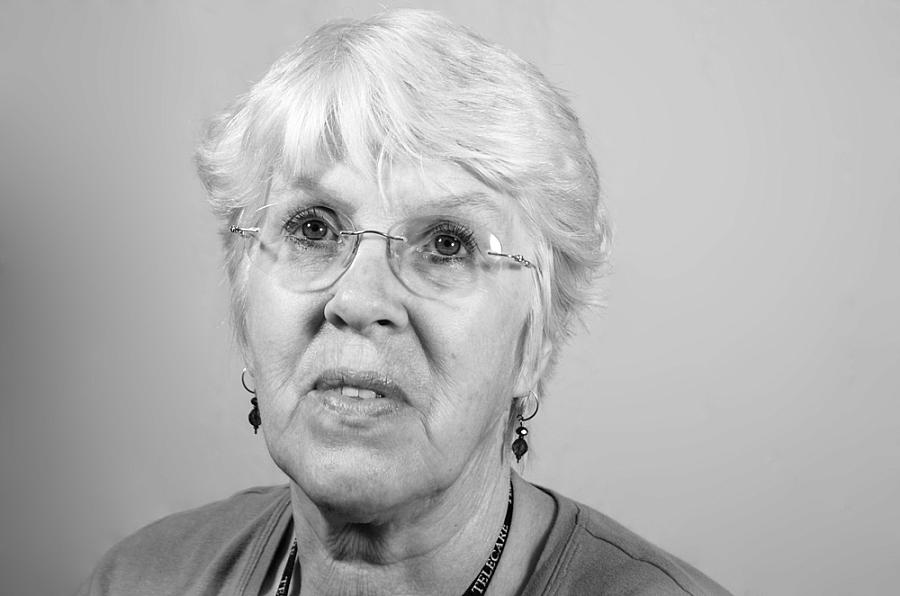

Monica Rojas, 49. (Lauren M. Whaley/CHCF Center for Health Reporting)

See Lauren M. Whaley's full photography gallery.

I finally landed on three – the local chapter of NAMI, the courthouse and mental health unit of the local jail, and a small family clinic called Aspen Family Medical. Those formed the backbones of the three main stories.

Joyce Plis, who runs the NAMI office, introduced me to several individuals and family members who had agreed to share their stories struggling to get appropriate care. She saw many, many people coming through her office, and told me that after years of deep cuts to county mental health services, she often doesn’t know how to help them.

“It’s almost impossible to send people some place,” she said.

I had worried that finding characters to illustrate the impact of the cuts would prove difficult – I soon found that I had more people offering to talk to me than I could possibly use. There was so much policy terrain to cover in the first day overview story that I could only use a fraction of their voices.

The second day story emerged as I spoke with Joyce Plis and others about the issue of criminalization. One of the newer volunteers at NAMI was a woman named Stephanie Hatfield, whose 24-year-old sister - who suffers from severe bipolar disorder and a mood disorder related to schizophrenia – was booked into the county jail after being arrested on a probation violation last fall. In December a judge declared the young woman incompetent to face charges and ordered her to Napa State Hospital to get well. But with no beds available at Napa, the young woman instead spent five months in the jail. I attended court hearings with Hatfield on a number of occasions, and also visited the mental health unit in the jail – a bleak looking place with tiny cells where inmates with mental illnesses are locked up for 23 hours a day, often off their medication as they wait for months for state hospital beds to open up – often staying long beyond what their sentence might otherwise require.

Of all the compelling personal testimonies I heard during my reporting, I was most touched by the experience of Hatfield’s sister. Watching tears of dread roll down Hatfield’s cheeks as she sat in a courtroom finally watching her little sister be released from jail – with nowhere to go and no real support services available to her – brought home the heartache so many families experience as their loved ones cycle in and out of the criminal justice system.

The third day story came about from a conversation with Matt Freitas, a nurse practitioner who runs a small clinic called Aspen and had decided to give free care to people with mental illnesses, having seen firsthand the difficulties his own schizophrenic daughter faced trying to get help. Originally Freitas had been a character in my Day One story, but I decided to pull him out so I could explore the possibilities and pitfalls of primary care providers providing mental health care in a community clinic setting, as well as delve more deeply into his compelling personal story.

The challenges I met

In reporting on mental health in this series and others, I have run into a few significant hurdles. First – the shortage of good data on mental health care at a statewide level. I was originally stalled for a few months as I tried to fight the now-defunct state department of mental health to give me data on cuts in the counties. I really wanted to see which counties had been hit the hardest.

I had done this for other health care stories with no issues, but the state mental health data was ultimately so compromised that it was deemed unusable. This was exacerbated by the fact that the state department of mental health was in the process of disappearing under realignment.

Also, while many families and individuals with mental illness were eager to participate in the story, we did meet resistance from others in the community – including some county employees and medical providers who worried about how stigma would impact their patients if they shared their stories. Others worried, more selfishly, I thought, about how the story might impact their ability to get funding for the programs they ran.

Shortly before publication, I almost lost Stephanie Hatfield, one of the main voices in my incarceration story because someone warned her that terrible things would happen to her career prospects in the county if she spoke out about her sister’s experience in the criminal justice system. It took a lot of coaxing by various people to bring her back.

Another county employee tried to prevent Lauren from taking photographs of people with mental illnesses at NAMI, saying these people weren’t able to give informed consent – despite the fact that they were all adults, none of them were under conservatorship and many said they saw sharing their stories as a way to reduce stigma in the community. After the story ran, we heard from a few of the individuals we photographed. They told us they were proud to have been featured in the photo spread.

The good surprises

That brings me to the best surprises in this story.

I found cooperation in all kinds of places I hadn’t expected it.

For one, I was impressed by those county officials who were eager to talk about cuts even when such cooperation wasn’t likely to cast any particularly positive light on their county.

I was also impressed with the compassion of certain individuals, like David Frost, the jail deputy who oversaw the mental health unit and said he thought the people inside were deeply misunderstood by society, and did not belong behind bars.

And I was especially impressed by the willingness of people with mental illness and their families to go public with their stories and their diagnoses. Going into this project, I had assumed that it would be difficult to find subjects who were willing to be named and photographed, due to the stigma that exists surrounding mental illness.

Normalizing Mental Illness: One mom's hope from CAhealthReport on Vimeo.

I was quite mistaken. Through NAMI, and community clinics like Aspen, I found many people who were eager to share their stories – both to combat stigma, and because they were concerned by the depth and breadth of service cuts and the impact those cuts were having on themselves and others.

Kim Green, whose daughter had been locked up in jail for months waiting to get into a state hospital, told me she had been waiting 20 years to tell her daughter’s story. Even when Green’s older daughter, Stephanie Hatfield, got scared and talked about backing out of the story, Kim Green stood strong in her conviction that she needed to speak up. In fact, she ultimately helped me convince Stephanie to remain part of the story.

Susan de Souza, who described herself as an “in between” -too sick to work, but too healthy to get care - told me she had gotten tired of the way people’s faces would change when she told them she had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

“I spent a lot of time feeling sorry for myself,” she said. “once I got past that, I decided I needed to do something positive. I want to be a voice. I don’t want people to feel lost and hopeless if they don’t have to be.”

I found their courage humbling and inspiring.

Reporting tips

Data:

As I mentioned, there’s a real shortage of good data on this issue. I am now working on a story that uses Medi-Cal mental health data. If you are looking for county-level data, that is something the state can provide to you. Individual counties can also offer you more detailed data on staffing, numbers served, and budget. In addition, the jails keep data on numbers of inmates with mental illness, and the police or local crisis center should be able to tell you trends in terms of the number of 5150 calls to pick up people deemed “danger to self or others.” Hospitals can also give you data on ER admits – if they’re willing to.

Finding individuals and families:

To find individuals and families who might be dealing with mental illness, I’d recommend starting with the local chapter of NAMI. Some of those are more active and engaged than others, but if you persist you should eventually get someone. I also have had luck with small community clinics – sometimes it’s helpful to shadow doctors, so they get comfortable with you, and the patients can meet you in person to decide if they feel comfortable.

Story ideas

The Affordable Care Act – are there enough psychologists and psychiatrists in your community to absorb the new expanded Medi-Cal population? Who is going to be left out?

Parity – The law now requires that insurers cover mental health care to the same level they cover physical health care. Is this happening?

Culturally and linguistically appropriate care – What are the disparities in access for different demographic groups? I believe you will find that there are lower rates of access to care especially in the Latino and some Asian communities. Rural areas also struggle with this.

Criminalization of mental illness – how many people are waiting in jail right now because they can’t access appropriate treatment?

The nexus of physical and mental illness – People with serious mental illnesses tend to die on average 25 years before the rest of the population. Why?

Transitional aged youth – Young people in their late teens and early 20s have a particularly difficult challenge, as they make the transition from children’s mental health care, which is often more readily available to them – to adult mental health care, for which they may or may not be eligible. Foster kids who are aging out are in particular need of services.

And, finally, any chance you have to showcase people with mental illnesses – or addiction problems - who are not ashamed to speak out about their experiences, I think can help have a normalizing effect on this issue and help combat stigma.