Cleaner air leads to stronger lungs in kids, but can the trend continue?

The Clean Air Act of 1970 may be over four decades old, but the political divisiveness over the law’s regulatory power shows few signs of abating. In a news analysis of President Obama’s ambitious use of the law, published last fall by The New York Times, the act was variously referred to as “the most powerful environmental law in the world” and “the granddaddy of public health and environmental legislation.”

The act’s longtime supporters attribute reductions in air pollution to the law’s passage and view it as a key lever in the effort to curb greenhouse emissions. Industry critics, such as the National Mining Association, lambast the legislation as a job killer and say Obama is overreaching in his energetic embrace of the law.

If this sounds like old politics, it is. But new research on children, published in the New England Journal of Medicine and widely covered in the press last week, supplies fresh evidence by which to evaluate one of the law’s most basic assumptions: Cleaner air leads to better public health.

This latest research – from the two-decade Children’s Health Study at USC – looked at how lung development changed from the age of 11 through 15 among three different groups of Southern California kids. The first group was tracked from 1994 to 1997, the next from 1997 to 2000, and the last from 2007 to 2010. Teams went to schools in five SoCal communities, where they recorded kids’ respiratory illnesses and measured their lung function with a device called a spirometer.

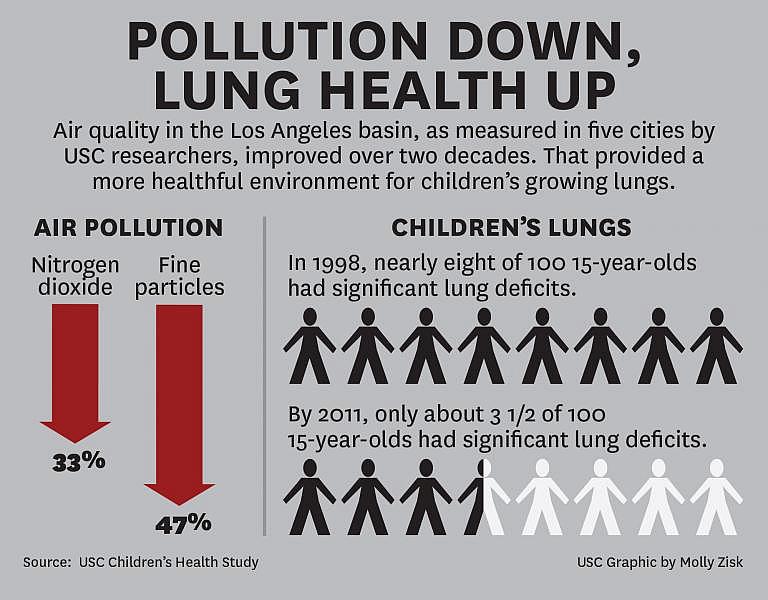

As the air quality “improved dramatically” over the course of the study, so did kids’ lungs, with the later cohort showing significantly more robust lungs as they entered early adulthood.

“The results of our investigation make it clear that broad-based efforts to improve general air quality are associated with substantial and measurable public health benefits,” the study states.

The study draws a straight line between the region’s improved air quality and more stringent air quality regulations. “Improved lung function was most strongly associated with lower levels of particulate pollution and nitrogen dioxide,” the study states, adding that “motor vehicles are a primary source” of such pollutants in the region.

Interestingly, the gains seen among the children who came of age from 2007 to 2010 also happen to neatly overlap with the Great Recession. Could the better-functioning lungs of kids measured during this period be a result of less vehicle traffic during the economic slowdown, rather than longer-term improvements from stricter air regulations? I asked the study’s lead author this question.

“The downward trend in air pollution levels appears to be durable, with pretty consistent declines over the 20-year period we have been monitoring levels,” said W. James Gauderman, professor of preventive medicine at USC’s Keck School of Medicine.

Those downward trend lines are born out by graphs published in the study that show steadily decreasing levels of particulate matter and nitrogen dioxide from 1994 to 2011, further ruling out the idea that the air quality gains are a minor blip. But those same trend lines do show particulates reaching new lows in 2010 before rising the following year. (It’s unclear if the uptick is due to a rebounding economy.)

Los Angeles has long been famous for seemingly apocalyptic levels of traffic and smog. But the gains in air quality have been real in recent years. Tony Barboza tracks the region’s air quality for the Los Angeles Times:

Peak ozone concentrations in Southern California are down to about one-third of what they were in the 1970s and '80s. The region's fine-particle pollution has been cut in half since measurements began in 1999. Emissions from cars, trucks, ships, power plants and industrial facilities are falling because of local, state and federal regulations that ensure the air will keep getting cleaner in the long term, regulators say.

And yet those broad regional gains can obscure important regional differences. California Endowment Health Journalism Fellow David Danelski, a reporter for Riverside County’s The Press-Enterprise, published a deeply reported series in 2013 that detailed the health effects of the Inland Empire’s consistent failure to meet clean-air targets.

“Air quality has improved dramatically since the 1970s, but still, on more than 100 days a year, Southern California is failing to meet clean air standards — and Inland residents are getting the biggest dose of pollution,” Danelski wrote. “Children appear to suffer the most. New avenues of discovery show that air pollution not only harms hearts, lungs and sinuses, it also penetrates the body’s natural defenses to invade brains and other vital tissues, laying the groundwork for multiple health problems.”

Those kinds of risks are perhaps one reason why Gauderman has urged the greater Southern California region not to rest proudly on its laurels:

Even though we’ve seen improvements in children’s health linked to improved air quality, we can’t get complacent. The projections are of course even more cars and trucks on our roads, more ships in our ports, more economic activity — meaning more factory emissions. So we have to continue to be vigilant about the emissions of these sources.

Those projections are already becoming reality. 2014 was the third busiest year on record for cargo volumes at the Los Angeles ports (though the recent worker-led slowdown may affect 2015 levels). Sooner or later, the gains from tighter emission standards and more stringent air regulations may run up against the economy’s growing demands.

Photo by David Herholz via Flickr.

Related posts

Combo of tobacco smoke, road pollution tied to childhood obesity

Press-Enterprise reporting details the high cost of dirty air