Found a stem cell clinic in a city near you? Here’s what you need to know

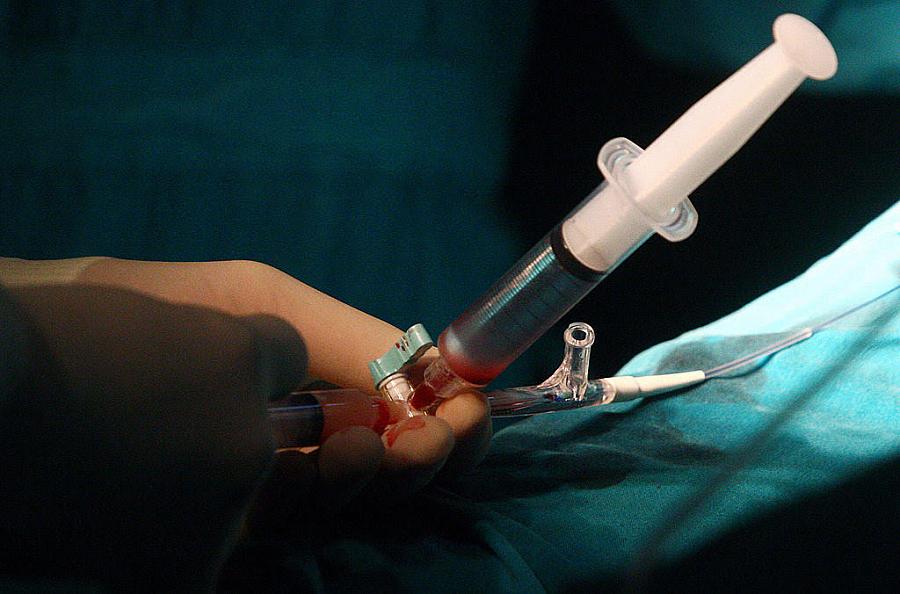

Surgeons perform a stem cell operation on a patient.

STR/AFP/Getty Images

The past few years have seen a huge boom in the number of stem cell clinics operating around the country.

The clinics began popping up in small numbers as early as 2009, and by May 2017, over 700 of them were operating across the United States – you may well have one or more operating in your community. California, Arizona, Texas, Colorado and Florida are the epicenters of this $2 billion dollar industry, which sells hope to ailing patients in the form of cell injections, under the guise of medical science.

But the stem cell industry is full of smoke and mirrors, and it’s alarmingly easy for consumers to find themselves putting their money and health in the wrong hands. The arena is ripe for watchdog reporting, so it’s important to know the signs of a sketchy clinic operating near you.

At stem cell clinics, customers pay on average between $5,000 to $10,000 a session in their bid to treat ailments like joint pain, heart failure, emphysema, and erectile dysfunction.

At least, that’s what the sales pitches promise. The evidence underpinning the industry is severely lacking, and in some cases, unproven injections can wreak havoc on patients’ health. Contaminated stem cell batches derived from umbilical cord tissue caused 12 cases of serious bloodstream infections back in December. In rare situations, injections have led to tumor formation or blindness. Earlier this month, The New Yorker and ProPublica jointly produced an illuminating exposé of the stem cell industry, describing “shoot-up parties” in which stem cell bank workers were given vials of cells for personal use — though some of the company’s own employees opted out of using the products because of concerns about safety or quality.

Dr. Ajay Kuriyan, an assistant professor at the Flaum Eye Institute at the University of Rochester Medical Center, says one of the biggest warning signs is when patients have to pay for stem cell injections.

The FDA tightened its stem cell therapy guidelines in 2017, and has been issuing warning letters to clinics it deems operating outside safe boundaries. However, the clinics have until 2020 to fully comply with the new guidelines. As stem cell biologist Dr. Paul Knoepfler notes on his website, “Three years is a long time for potentially non-compliant clinics to still be raking in the dough from patients.”

That said, there are cases in which stem cell treatments have led to improvements in patients’ lives in ways that standard treatments did not. That includes patients suffering from the “dry” version of age-related macular degeneration. Although the disease has historically been considered incurable, patients in rigorous clinical trials have seen reverses in their vision loss. On the other hand, some patients receiving treatment at less reputable clinics have ended up blind.

So how does one spot the differences between sound science and “snake oil” solutions?

Dr. Ajay Kuriyan, an assistant professor at the Flaum Eye Institute at the University of Rochester Medical Center, says one of the biggest warning signs is when patients have to pay for stem cell injections. Kuriyan treated one of three female patients who went blind after receiving injections from Bioheart, Inc., now known as U.S. Stem Cell, and coauthored a report in the New England Journal of Medicine detailing their cases. While Kuriyan was not involved in administering the initial stem cell treatments, he cared for one of the women seeking help after she experienced complications. All three patients paid $5,000 for the injections that ultimately took away their eyesight.

Kuriyan explains that since no stem cell treatments are FDA approved and on the market, the only legitimate uses of stem cell therapies would be through clinical trials, in which patients are not expected to pay anything.

Another sign to watch for is whether the clinic provides health care beyond stem cell injections. Kuriyan says that medical establishments offering stem cell-based therapies through clinical trials should always offer standard-of-care treatment options as well, rather than only pushing stem cells. In some cases, doctors who have been stripped of their medical licenses have turned to administering stem cell therapies, so checking to make sure the establishment offers standard medical care in addition to the stem cell therapy is a useful vetting tool.

Another important distinction, according to Kuriyan: Even if an experimental stem cell treatment is listed on ClinicalTrials.gov, that’s not an endorsement. “ClinicalTrials.gov is just a repository, it’s not a stamp of approval,” Kuriyan explains. In the cases of the three blinded patients, two of them were aware that the clinic had listed a trial on ClinicalTrials.gov describing a procedure in which subjects would have their own stem cells harvested from their fat and injected into their eyes, with the goal of improving their vision. While one patient thought she was participating in the trial, none of the patients signed paperwork that actually enrolled them in the trial.

Another sign to watch for is whether the clinic provides health care beyond stem cell injections. Medical establishments offering stem cell-based therapies through clinical trials should always offer standard-of-care treatment options as well.

Reporters should keep in mind some handy resources. Organizations like the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) provide online resources, including a patient handbook to answer common questions. The handbook recommends finding out whether the treatment in question has been approved by an institutional review board (IRB) or ethics review board (ERB), which regularly evaluate research done on humans to make sure patients’ rights and safety are protected.

The FDA notes that any treatment under consideration should either have FDA approval, or the providers should be operating under an Investigational New Drug (IND) application that the FDA issues to experimental trials. The FDA advises potential trial participants to ask for proof of FDA approval or the trial’s FDA-issued IND number before moving forward with treatment.

Some of the biggest warning signs to look out for are clinics touting patient testimonials rather than scientific evidence, providers claiming they can treat multiple illnesses with the same type of cells, and the lack of a clear explanation as to where the cells come from or how they are processed before being delivered into the body, according to the ISSCR.

Kuriyan urges patients considering an experimental therapy to talk with their regular doctor before moving forward. Physicians with expertise in regenerative medicine can also help reporters figure out what questions to ask the stem cell providers. They’ll know whether the evidence supporting a given treatment is sound and sufficient. Finally, if patients encounter what they believe is a questionable stem cell clinic in their community, Knoepfler’s website offers a series of suggestions on how to report those providers to regulators.