Busted toilets, peeling paint, sewage backups, lice: a peek inside juvenile lockups

This article and others in this series were produced as part of a project for the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism’s National Fellowship, in conjunction with the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

Powerful lawmaker calls for juvenile justice review in wake of Herald series

Juvenile justice chief defends agency, calling abuses ‘isolated events’

An officer used a broom to beat juveniles into submission. They called it ‘Broomie.’

NAACP demands reform as lawmakers plan tour of lockup where youth was fatally beaten

Criminal record? Horrible work history? Florida juvenile justice would still hire you

At this juvenile justice program, staffers set up fights — and then bet on them

Dark secrets of Florida juvenile justice: ‘honey-bun hits,’ illicit sex, cover-ups

Lightning blasted his shoes off — and illuminated a pattern of abuse by staff

How small rebellions by Florida delinquents snowball into bigger beatings by staff

FIGHTCLUB: A Miami Herald investigation into Florida’s juvenile justice system

Photos from an inspection show conditions in the Miami-Dade juvenile lockup. When conditions had not significantly improved by the time lawmakers paid a visit months later, the superintendent received a reprimand. Florida Department of Juvenile Justice

On a Monday in early October, the top administrator at the Bradenton youth lockup issued a terse order to subordinates:

“Do not flush.”

Three days earlier, on Sept. 30, the Manatee Regional Juvenile Detention Center’s plumbing went haywire. While youths in the lockup were showering, the drains from three living units and the infirmary began “to overflow with sewage,” a lockup supervisor wrote in an email.

“The water overflowed out into the ... hallway and the courtyard. After about 20-30 minutes, the water began to go back down the drain. We cleaned all the mods and the facility, and tried our best to get rid of the smell that was left behind.”

Like many, if not most, of the state’s juvenile lockups, Bradenton’s is showing its age. Built in 1970, the 42-bed detention center now suffers from a variety of maintenance issues. The structural, plumbing and sanitation problems had remained largely hidden — until recently.

After the Miami Herald published a six-part series on the state’s long-troubled juvenile justice system, lawmakers made surprise inspections of the detention centers in Miami-Dade and Broward counties. A legislator from Miami declared conditions there to be “horrible, horrific, deplorable.” In Broward, two girls showed visitors ant bites up and down their legs. The detainees said staff told them to use bleach and a rag for treatment.

It appears to have taken the “unannounced” visits — the Broward one apparently leaked out in advance — to prod Department of Juvenile Justice administrators to take long overdue action. “We have had our first legislative visit and have learned a few things,” DJJ’s assistant secretary for detention, Dixie Fosler, wrote in an Oct. 19 email, one of many obtained by the Herald through a public records request. She added: “All toilets and sinks need to be clean and in working order. All showers need to be operational. All [air-conditioning] units need to be functioning properly. All rooms need to be graffiti-free.”

Four days later, the Miami-Dade detention center’s top administrator was reprimanded. Though the Oct. 23 reprimand itself is vague, a DJJ spokeswoman confirmed that Superintendent Steve Owens was disciplined for failing to properly maintain the 126-bed detention center after earlier inspections had turned up a slew of deficiencies. “Following failure to quickly resolve identified cleanliness and maintenance issues,” the lockup was placed on a corrective action plan, said spokeswoman Heather DiGiacomo.

“It is the responsibility of the detention center superintendent to see that staff and facility meet or exceed our expectations and any failure to meet that responsibility is completely unacceptable,” DiGiacomo added. “Staff were held accountable and action has been taken to solve these issues as quickly as possible.”

Following the Herald’s reporting on conditions inside the Miami and Fort Lauderdale lockups, Gov. Rick Scott proposed $11.6 million in additional spending for “the necessary repairs and maintenance of detention, probation and residential facilities.”

Records obtained by the Herald show that, as early as this past July, DJJ inspectors had identified significant problems in the Miami lockup: In three living areas — modules two, three and six — there were “physical plant and maintenance issues,” a July 18 report said. In module three, there was “grime and mold on toilet walls, graffiti in the bathroom stalls” — including some tags that were gang symbols. Module six had missing tiles in the showers, and graffiti as well.

Photos from the inspection obtained by the Herald show a gaping hole in one wall, exposing plumbing fixtures; widespread graffiti, peeling paint, moldy bathroom floors, caked-on dirt and grime on the concrete slabs where youths sleep, and filthy bathrooms and showers.

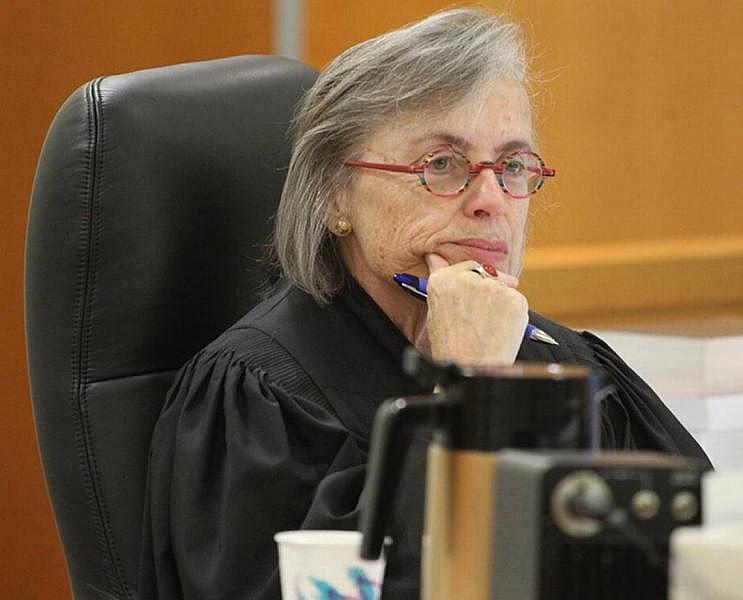

“So many of the children in our detention centers, through no fault of their own, only know impoverishment and deprivation. It is our job, as an institution, to rise above that and show them that their lives are valuable and we expect them to make a positive contribution to our community,” said Miami-Dade Juvenile Court Judge Cindy Lederman, a 20-year veteran. “The conditions in our detention centers only reinforce their impoverishment and deprive them of hope. We should be ashamed. This is not rehabilitation.”

‘We should be ashamed,’ said Judge Cindy Lederman, speaking of the physical condition of the Miami-Dade juvenile lockup. ‘This is not rehabilitation.’ Miami Herald staff

The Herald shared photos from the Miami lockup with Vincent Schiraldi, a senior research scientist and adjunct professor at the Columbia University School of Social Work. Schiraldi was director of juvenile corrections in Washington, D.C., from 2005 until 2010, and then commissioner of New York City’s youth probation department until 2014. He said the pictures “depict how routinized deplorable conditions have become in Florida’s youth prisons.”

“Terrible. What else can you say?” said Paul DeMuro, who has worked as a juvenile justice administrator and consultant for 41 years, including a stint as a federal court-appointed watchdog in Florida. He also viewed the photos. “They’re disgusting. And inhumane. You wouldn’t tolerate this in a public school or any other place where kids are served.”

Miami’s lockup was built in 1977, in a subdivision named after the neighborhood’s most illustrious structure, the old Fritz Hotel. Conditions in the detention center have been notorious virtually since the building’s construction. In 2003, a Herald reporter investigating the death of a detainee watched a toddler vomit a fast-food hamburger onto the floor of the lockup’s waiting room. The dried mess remained there days later when the reporter returned.

Vincent Schiraldi, former head of youth corrections in Washington, D.C., said photos from Miami’s juvenile lockup ‘depict how routinized deplorable conditions have become in Florida’s youth prisons.’

The juvenile justice complex at 3300 NW 27th Ave. had become so decrepit in recent years that many juvenile and child welfare court judges were refusing to work there, and a new $110 million, 14-story modern judicial center was built downtown. The lockup remains, though. Administrators for state children’s programs moved into the empty gray concrete courthouse.

DJJ administrators acknowledge the challenge of maintaining buildings that are often far older than the people who work in them. “These are very old buildings,” said DiGiacomo, the agency spokeswoman. “The department is not turning a blind eye to issues in our facilities.”

“Many of these buildings are more than 25 years old. That does make them aged buildings, and we do have maintenance issues. When the department becomes aware of maintenance issues, we address them.”

The crumbling structures and plumbing can have consequences beyond the obvious.

At the same time that administrators were dealing with sewage leaks and broken toilets at the Bradenton lockup, youths there were complaining about an infestation of lice. Youths said they sometimes couldn’t take showers, said Rebecca Wilson, an assistant public defender who oversees the defense of youthful offenders in nearby Sarasota County — and whose clients are detained in Manatee. And when they could, the showers often were cold and short. Treating lice, of course, requires showers.

A lice outbreak was reported recently at the Manatee Regional Juvenile Detention Center. Zack Wittman

DJJ records obtained by the Herald indeed show that the Manatee lockup spent $227 for 20 bottles of “Rid Lice Shampoo” about the same time, early October, that Superintendent Terry E. Carter was telling his subordinates to “not flush toilets, run the water in sink, or pour water down the floor drains” in three separate living areas.

Wilson remembers the first time she walked inside the Manatee Regional Juvenile Detention Center 18 years ago. “I heard the blinds move, and I turned around to see a huge cockroach.” She said conditions have not improved markedly since.

Exacerbating the problem is the fact that conditions inside the state’s lockups and residential programs remain largely hidden from anyone who does not work for DJJ. If the plumbing, ventilation, sanitation and physical conditions of the facilities are in disrepair, there’s virtually no way that a parent, guardian or even most lawyers would know it.

DJJ’s Office of Program Accountability performs oversight of each facility, and the reports that result are available online. The evaluations include such things as management accountability, mental health and substance abuse treatment, medical care, and safety and security. The reports — which grade each facility on about 100 indicators — do not include any measures of building maintenance, cleanliness, sanitation, plumbing or ventilation. And such information is not readily available elsewhere.

Brad Dalton, a spokesman for the state Department of Health, said his department inspects the kitchen and pharmacy — if one is present — at juvenile lockups and residential programs. Some inspections include classrooms. But inspectors do not oversee living quarters, or the showers, toilets and air conditioners within them.

The same is true for adult prisons.

Other congregate living facilities that don’t involve detainees or prisoners, though, do undergo routine inspection, including nursing homes and assisted living facilities.

“These are human beings. There has to be some level of accountability,” said Robin Bartleman, a veteran Broward County School Board member. “We have to make sure conditions are habitable for these children. These are publicly owned facilities. They need to be taken care of, and regularly maintained. DJJ has a responsibility to taxpayers to take care of these facilities and take care of the children who are housed in these facilities.”

Bartleman, who was first elected to the Broward School Board in 2004, said she has been in and out of the Fort Lauderdale lockup for years, and has seen only modest improvement — depending on the superintendent at the time.

“The first time I went there,” Bartleman said, “I was horrified. These are people’s children. They are being held there innocent until proven guilty.

“A couple of times when I visited there were plumbing issues, and the toilets were overflowing. Some of the units were without air conditioning. The air wasn’t working, and there was not a lot of ventilation in the rooms,” Bartleman said. Broward’s lockup was built in 1980 or 1981 — property appraiser records are unclear — and defenders and some local elected officials like Bartleman have lobbied for it to be replaced.

“Every time I leave there, I’m sad,” Bartleman said. “Something has to be done.”

Conditions inside DJJ’s 21 lockups and 53 privately run residential programs have come under intense scrutiny in recent weeks after the Herald published its six-part investigative series, called Fight Club. The series detailed the widespread use of unnecessary and excessive force; officers and youth workers who outsource discipline by designating youths as enforcers; sexual misconduct by staff, some of which goes unreported; and a propensity of employees to neglect the medical needs of teens, sometimes calling them fakers.

A week after the series was published, a group of five state lawmakers from Miami-Dade County made a surprise inspection of that county’s lockup. After the 90-minute tour ended, members of the delegation expressed disgust about what they saw.

“The living conditions are horrible, horrific, deplorable,” said State Rep. Kionne McGhee, a Cutler Bay Democrat. “Unacceptable. Unacceptable. And we want answers.”

The Miami-Dade Regional Juvenile Detention Center, dating back to 1977, has seen better days. The adjacent juvenile courthouse recently moved to newly constructed high-rise quarters in downtown Miami. Miami Herald staff

McGhee and his colleagues said they saw mold, mildew, leaking toilet water, broken showers and living quarters with no running water.

Broward legislators, as well as a representative of the NAACP, visited the Broward lockup on Nov. 3. Most telling, the lawmakers said, was the smell of fresh paint wafting through the hallways. State Rep. Bobby B. DuBose, a Fort Lauderdale Democrat, said detainees said they were told to spruce up the place and had been tapped to do the painting themselves, suggesting that the “unannounced” visit was not truly a surprise.

During the tour, two girls lifted their pant legs and showed DuBose a rash of ant bites. The girls said staffers there had instructed them to use bleach to treat the bites.

“I told the [DJJ] secretary: I don’t think this is your fault,” said state Rep. David Richardson, a Miami Beach Democrat who organized the tour in Miami, and is sponsoring legislation that would grant lawmakers the authority to make surprise inspections at DJJ lockups and programs — as they are able to do at adult prisons.

“You haven’t been funded adequately, and that’s on the governor’s office and the Legislature,” Richardson said he told Secretary Christina K. Daly. “You haven’t been given the money you need to do the work. You were given a tube of glue and some yarn and paper clips and rubber bands, and told to build a mausoleum.”

Mark Steward, who was director of the Missouri Division of Youth Services for more than 17 years and is credited with turning it into a national model, also viewed photos of the Miami lockup. The disrepair, he said, sends a signal that detainees are not worthy of respect. “Safety, cleanliness, supervision — those are the basics, and they certainly don’t appear to be met from those photos. The place is filthy and neglected,” he said.

“When kids go into squalor, they react to the conditions,” Steward added. “It encourages the feeling that nobody gives a damn about me, so why should I care?”

[This story was originally published by the Miami Herald.]