Cleveland doulas fight infant mortality in their neighborhoods, one birth at a time: Saving the Smallest

This reporting is supported by the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism National Fellowship. Other stories in this series include:

Meet Birthing Beautiful Communities founder Christin Farmer: Saving the Smallest

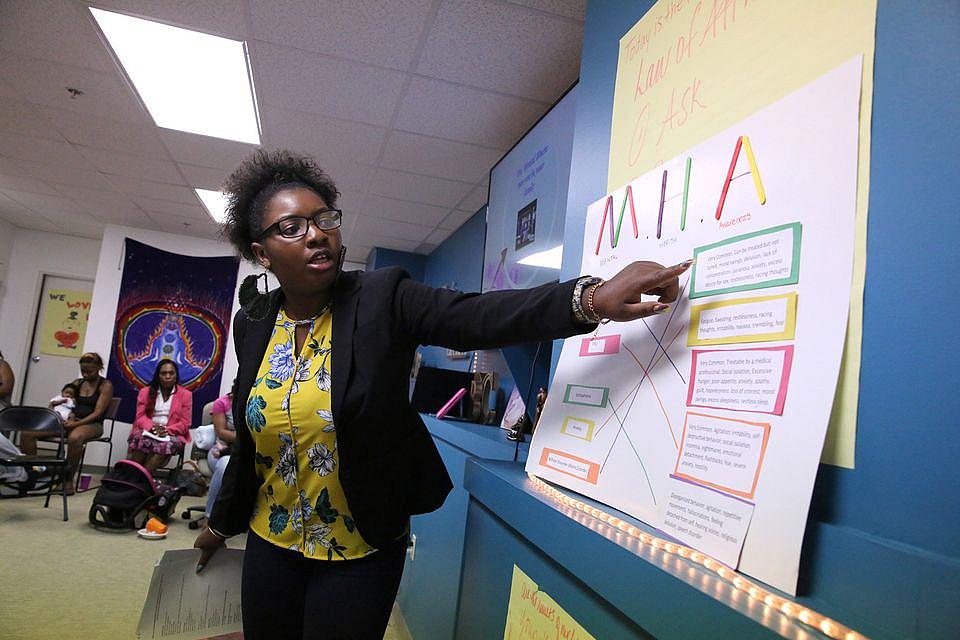

Program assistant and a doula herself, Rod'Neyka Jones discusses mental health issues at a Birthing Beautiful Communities teaching session of expectant and new mothers taught by program assistant and doula Rod'Neyka Jones on Thursday, June 29, 2017. (Thomas Ondrey/The Plain Dealer)

CLEVELAND, Ohio -- It's 11:32 p.m. on a Friday night, and 31-year-old Alisha Samuel is entering her sixth hour of natural labor at Cleveland Clinic's Hillcrest Hospital. The first-time mom is ready to give up.

"Call them, seriously," she moans, stuffing her face into a pillow between contractions that are now about a minute apart. There are no doctors or nurses in the room. Jay-Z's 2001 album "Blueprint" plays on an IPhone positioned next to her bed.

Samuel is on her knees on the bed, surrounded by her mother, cousin, boyfriend and doula -- or birth attendant -- who have spent the past several hours cheering her on and reminding her why she chose a natural delivery.

"I need something. I'm giving in. I'm begging you guys, please," says Samuel.

It's her doula, 24-year-old Amber Green, who answers. Green is 24, a Cleveland native and Euclid resident who is 8 1/2 months pregnant herself. Her white T-shirt, taut over her round belly, reads "I've met God and she's black."

"You can do this. You're doing it," Green tells Samuel, massaging her back. "Today is the day you meet yourself."

Green works with Birthing Beautiful Communities (BBC), a non-profit whose aim is to reduce the high infant mortality rate in black neighborhoods in the Cleveland area by providing continuous support to women during pregnancy, delivery and through the baby's first year of life.

Samuel's full-term healthy birth today would defy many odds: the preterm birth rate among black women in Ohio is 45 percent higher than all other women, and the black infant mortality rate in Cuyahoga County is more than three times higher than that of white infants, reaching levels seen in developing nations in some Cleveland neighborhoods.

Research suggests that employing doulas positively affects birth outcomes for mothers and infants, including lower rates of C-sections, epidural use and episiotomies, higher rates of spontaneous labor, and higher Apgar scores (which rate how well the baby is doing after birth).

However, the use of doulas is low overall, only about 6 percent of births. Among low-income and minority women, who have the highest rates of infant and maternal mortality, access to a doula is hindered by high cost and the limited number of providers of color. It's hard to tell how many black doulas there are throughout Ohio, but the number is low: There are 10 or fewer on available lists compiled by birthing nonprofits.

Since its launch in 2015, BBC has likely doubled that number; the group now employs 15 doulas, and has trained another three Cleveland-area women to work as doulas on their own.

BBC doulas are residents of the communities they serve, which include eight Cleveland neighborhoods, as well as East Cleveland, Warrensville Heights, Euclid and Maple Heights. Their training is free, as are their services, as The Cleveland Foundation and the Ohio Department of Medicaid have given the organization more than $600,000 in grant funding.

The BBC model has proven so promising, with only one early birth among its 39 deliveries this year, that the Cleveland Foundation recently agreed to give the group an additional $127,000 to further expand the program and to help amass the necessary evidence to make BBC's services a covered Medicaid benefit in Ohio.

It's quite a feat for a fledgling program that began three years ago entirely in the imagination of its then 28-year-old founder, Christin Farmer.

Getting to the root of the problem

Coretta Daniel, center, delivered her second baby, Zaria, with the help of BBC doula and founder, Christin Farmer. She says the group's services are "so needed" in her community, and can't wait to see them expand. (Thomas Ondrey, The Plain Dealer)

Farmer, who is now 31, sits on a folding chair in the bright fourth-floor offices of BBC on a recent summer day, balancing a client's 2-month-old baby girl on her knee. The room is as homey as you can make the brand-new downtown office space in the Agora building on Euclid Avenue: white Christmas lights, pregnant woman figurines and framed pictures adorn the shelves, toddlers crawl across the carpet and play with toy trucks and balls, while women in all stages of pregnancy sit, some balanced on yoga balls eating plates of food.

In the chair to Farmer's right 26-year-old Coretta Daniel cradles her 4-month-old daughter, Zaria, while her 16-month-old son plays with a plastic yellow ball at her feet.

Farmer was Daniel's doula for Zaria's birth, and helped her to deliver her naturally after having her son via cesarean, a method called VBAC (vaginal birth after cesarean). Daniel, who now lives in Lake County, grew up in the Buckeye-Woodhill neighborhood on the city's East Side, where both preterm birth and infant mortality rates are higher than average.

Tonight, she's sitting in on a BBC class on postpartum depression with about 15 other women, periodically nodding her head in agreement as she listens. She suffered "hugely" with postpartum depression after the birth of her son, Charles Jr., she says, mostly because she didn't have a lot of support.

Farmer's younger sister, Rod'Neyka Jones, also a doula, is teaching the evening class. It's one of a series offered by BBC to any of its clients, this one about what symptoms of depression to watch for in the weeks after birth, and how hormone levels can influence mood during and after pregnancy. But it's also about mental illness in the black community, and how little it's discussed, treated and understood.

Jones shares her own experience of being diagnosed with depression and using medication to manage her symptoms.

"You'd never know I suffered depression by looking at me," she says. "It happens to a lot of people."

Several women signal their agreement with nods and raised hands. More start nodding when Jones moves onto her next topic: post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD.

She's quick to explain that it's not just about being in combat, that women who experience or witness life-threatening events in their childhood, such as physical or sexual assault, and teens or adolescents who witness violence, can also suffer PTSD.

"Just being born into the inner-city of Cleveland is a stressful environment. You see a lot of things you shouldn't," Jones says.

Jones and Farmer grew up together in Hough with their mother, the fourth generation to live in the neighborhood.

The stress of poverty, lack of education and opportunity, and proximity to violence "puts stress on your body, including your baby, during pregnancy," and can cause some babies to be born too early, Jones tells the group.

It's a theory that is supported by an increasing body of research, including by a group working at The Ohio State University.

Farmer believes maternal stress is central to the infant mortality crisis in the black community, and that its roots lie in a systemic racism that cuts across economic lines.

It's why the BBC doula curriculum includes a component on stress, anxiety and depression, and why tonight she brings up the intergenerational effects of racism on African American women and families.

"Infant mortality affects black women across all socioeconomic statuses," she explains later. "But there's nothing genetically wrong with us -- black women in other states don't lose babies like we do. Black women in other countries don't. So then the question is, what's really happening?"

Farmer acknowledges the conversation makes some uncomfortable. But she refuses to be silent about it in any setting, whether with her clients or in her policy work, where she consistently and successfully helped push for race to be a primary consideration while sitting on the advisory board for the newly-released strategic plan of the city-county infant mortality initiative, First Year Cleveland.

"She helped us all understand the issue of structural racism," says First Year Cleveland Executive Director Bernadette Kerrigan. "She has a beautiful way of listening to all voices in the room, but always keeping the voice of the expectant mother and her family as the loudest and most important."

Sustainability key question for BBC's future

Doula Myranda Majid, right, of Birthing Beautiful Communities, discusses meal planning with expectant mother LE Tisha Hopkins during a pregnancy checkup at University Hospitals Rainbow Babies & Children's Hospital. (Thomas Ondrey, The Plain Dealer)

LE Tisha Hopkins, 42, is five-months pregnant with her fourth baby. In addition to her age, she's dealing with several other issues that could impact her pregnancy: She's working on quitting smoking, managing chronic depression and schizophrenia, and has recently had a piece of her spine removed to alleviate nerve pain.

She's also lost her appetite and is losing weight rather than gaining.

Her BBC doula, Myranda Majid, is with her at a scheduled prenatal appointment at University Hospitals MacDonald Women's Hospital in late June.

When Dr. Kateena Addae-Konadu, a second-year resident, offers Hopkins the services of a nutritionist to help her with her appetite, the expectant mother laughs and points to Majid, standing in the corner of the room.

"I've got a nutritionist -- my doula," she says.

Majid spent the 20 minutes before the doctor arrived talking about ways to get Hopkins to eat more small meals throughout the day, pulling recipe printouts from her purse and handing them to Hopkins' husband, Josh.

Diet is one of the many things Majid and other BBC doulas help clients with. They've also scrambled to find a stove and microwave for a mom who had no way of cooking at home, and regularly deal with housing, transportation, daycare and employment issues that affect their clients and families.

Majid joined BBC in 2015. She didn't know much about infant mortality then, "I guess I was in a little bubble," she says. She just wanted to help women have more positive deliveries.

She had wanted for years to be a doula in her community, but didn't think it was economically feasible because she couldn't find anyone else doing it and she didn't think enough people would be interested in the services to support herself.

The organization's grants mean she and the other BBC doulas are now paid $20 per hour for their work, plus a $500 flat fee for every birth they attend. To maintain the model and replicate it in other neighborhoods, BBC will have to find a more sustainable way of funding its doulas.

At least two states, Oregon and Minnesota, have recognized the potential for cost-savings and allow Medicaid reimbursement for the use of a doula. Studies in these two states and Wisconsin have concluded that reimbursement for doula care saves money. Because doulas are not licensed healthcare providers, obtaining Medicaid coverage for their services is more complicated.

The Cleveland Foundation hopes to help BBC build the evidence necessary to show Ohio Medicaid (and other insurers) that its model saves money over time. Lillian Kuri, vice president for strategic grantmaking, arts and urban design at the foundation, says BBC has the potential to be a national model for reducing infant mortality in the black community.

"It's early, but it's extremely promising, which is why we're doubling-down on our commitment to [Farmer] this year," she says. "If we're able to do that, and change the way of doing business, it could also change national policy."

That's what occupies most of Farmer's time now, not birth work. And while she misses being a hands-on doula, she also loves being part of driving policy and system change.

"That gets me excited, because that's what can actually change things and save lives," she says. "Changing the system is what will make the biggest difference for our moms and babies."

Defying the odds

Alisha Samuel, 31, holds her new baby daughter Bailey Amira Mae Robertson just minutes after she was born July 14th. (Lisa DeJong, The Plain Dealer)

BBC's newest baby, all 7 pounds, 8 ounces of her, arrives healthy and safely (and without the help of an epidural) less than 20 minutes after Alisha Samuel thought she could push herself no further.

Bailey Amira Mae Robertson comes so quickly, in fact, that Samuel doesn't have time to get off her knees. She delivers with her head at the foot of the hospital bed, another doctor still tying a mask around the OB-GYN's face as she catches the baby's head.

In the minutes after delivery, grandma, dad and Samuel's cousin snap pictures and tell Samuel over and over how well she did.

Meanwhile, Amber Green, Samuel's doula, is quietly reminding the nurses that Samuel wants Bailey to stay connected to the placenta for at least a minute, that she wants to save her placenta for encapsulation and later ingestion (believed to have health benefits for new mothers) and that she wants skin-on-skin contact as quickly as possible.

Within 5 minutes, Bailey is nestled into Samuel's chest, making her first attempts at nursing. Green coaches the new mother: "It's not going to feel great, but if it hurts a lot, she's probably not latched on right," she says.

Samuel's eyes widen and she grimaces when Bailey's tiny mouth finds its target.

"Ooh, girlfriend!" she says, looking down at her daughter. "We're going to have to talk."

[This story was originally published by Cleveland.com]