Editor's note: This is the second of three stories examining how policy decisions and a limited investment into the Virginia Department of Health led Latinos to being among the most likely to get infected, hospitalized and die in the first two years of the pandemic. Read Part 1 here.

Essential and Overlooked: Federal relief changed Virginia's COVID response. For some Latinos, help came too late.

This project was produced as part of a larger project for USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2021 National Fellowship.

Other stories in this project include:

Part 1: Essential and Overlooked: How decades of inaction failed Virginia's Latinos during COVID

Richmond Times-Dispatch

Her final messages to him were all desperate variations of "are you still alive?"

Please don't be dead.

I can't do this without you.

Don't make me do this without you.

For much of the past 20 months, Maria Fuentes has hidden her grief so she doesn't have to tell her three grandchildren why he never answered them — why he never came home.

When they ask why they haven't seen him, she says he left for his construction job before they woke up and returned long after they went to bed. Sometimes, she concocts stories about how he went back to Guatemala to take care of his family and cell service isn't too great over there.

Sometimes she lets herself believe it, too — to pretend, however briefly, that her husband Yuki Mendez didn't die in a place he wouldn't have chosen: with coronavirus in a hospital bed and on a ventilator at 40 years old.

"The truth would break them," she said in Spanish, shaking her head.

Left unsaid on the couch of the Southwood townhome they shared for seven years was how for her, the truth almost did.

It's been nearly two years since Maria Fuentes last held her husband's hand. Sometimes, she still reaches for it. Sometimes, she peeks out her door at 5 p.m. when the construction crews start arriving home as if he'll be among them. Instead, there's only the reminder of the virus that killed him. Eva Russo/Times-Dispatch

Two years into the pandemic, COVID is killing more Virginians every day than it was when Mendez died on July 28, 2020. But accepting the scale of mourning has become routine — a ruthless tally reduced to faceless numbers in hopes that looking away can mean finally moving on from an ongoing crisis.

There are an estimated 9 million people like Fuentes in the U.S. reeling from the loss of a loved one to COVID, seeing the country’s rush to heal and return to a normal that will never be within their reach.

"Normal” led to the virus killing so many Latinos in the U.S. within two years that their life expectancy dropped by almost four years. “Normal” allowed nearly 70% of the 1,022 recorded deaths among Latinos statewide to occur in the first half of the pandemic, the same time frame the Virginia Department of Health reported Latinos ages 35 to 44 were dying at 11 times the rate of their white counterparts.

And “normal” in Virginia meant essential workers and immigrants like Mendez, immunocompromised residents and people inside nursing homes and prisons would be left in a pandemic to fend for themselves.

The speed with which the virus invisibly burned through Virginia’s Latino communities between March and September 2020 can be seen as an indictment of a generation of federal and state leadership, which repeatedly neglected to pass paid sick leave, prioritize language access or adequately equip its public health department with the tools to thwart disease ahead of a crisis.

A five-month investigation from the Richmond Times-Dispatch found that without the federal money arriving in April, not even one of the richest states in the U.S., led by physicians who swore to prioritize the most vulnerable, could protect them.

For Mendez and others, the help arrived too late.

When the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention deployed its first all-Latino COVID response team to Southwood in June following infection rates so severe that local health districts pleaded for help, he was already in the hospital.

He was deteriorating when Google Translate popped up on the VDH site for COVID information on June 18 or then-Gov. Ralph Northam’s first partially-in-Spanish COVID briefing, where Northam lamented how Latinos were nearly 50% of the state’s cases and more than a third of hospitalizations.

Virginia’s workplace protections that could have helped when there wasn’t enough protective equipment on the construction site went into place July 27, 2020.

Mendez died the next day.

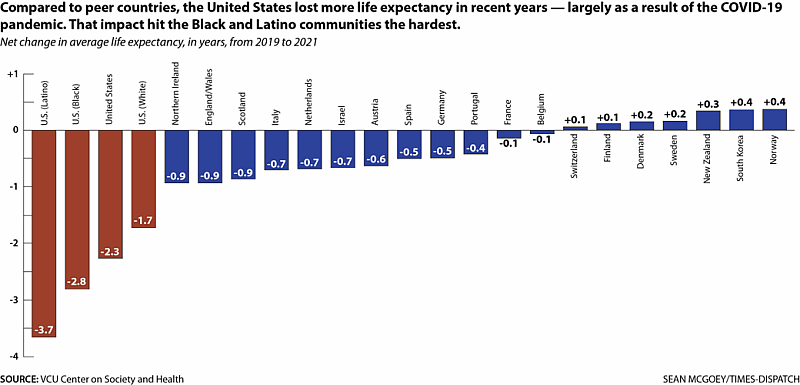

In the first two years of the pandemic, the United States experienced a greater loss in life expectancy than 19 other wealthy countries. Black and Latino Americans suffered the most. Sean McGoey

For others who continue to navigate being uninsured essential workers living in multigenerational households without access to quality health care or paid sick leave, VDH’s record $1.4 billion in federal COVID grants isn’t a substitute for legislative action.

And it isn’t a permanent solution to sustaining a state health department where at least 43% of the full-time workforce in 2021 was propped up by contractors forced to resign when the federal money funding them expires.

The federal relief also couldn't undo the loss of time after more than 20 years of unheeded warnings from public health officials and community organizations signaling how a lack of long-term funding and urgency could prove disastrous in an emergency.

"Americans are great innovators when there's a crisis," acknowledged Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., who led Virginia through H1N1 and the financial crisis as governor. "Then we sometimes turn our attention away when there isn't."

In interviewing nearly 70 VDH workers, community leaders, public health experts, legislators and residents at Southwood — a neighborhood home to the largest concentration of Latinos in Richmond — The Times-Dispatch found that the sluggish pandemic response allowed the first year of the pandemic to play out as an answer to who loses when there is a scarcity of resources.

Solutions will require a "genuine desire to work at this problem for a long-period of time," said Madhav Marathe, division director at UVA's Biocomplexity Institute — which has conducted infectious disease modeling for more than 20 years and advised VDH throughout the pandemic.

"If we don't do that, we have essentially lost all the difficult lessons we learned from this, and all of us paid a tremendous price for it," he continued. "This is not just one crisis. There are many more awaiting us ... we should not forget. I really hope we do not forget."

There were moments before March 2020 when it didn’t seem like everything was aligning against Maria Fuentes. She survived witnessing her 18-year-old son’s final minutes when he was killed in Honduras six years prior, before he could fulfill his dream of owning an auto-repair shop. She followed through on her promise to protect her then 11-year-old daughter by chasing hope in the U.S.

In South Richmond, she found a “till death do us part” kind of love — someone to face life’s challenges with — who took care of her when her aching hands began to weaken and a hemorrhage left her briefly unemployed.

The first wave of coronavirus upended years of moving forward.

By late March 2020, Fuentes lost her job as a housekeeper. Clients started canceling. Schools began sending kids home. The working-class immigrant neighborhood that became her support system was soon overwhelmed with sickness, with rent looming ahead.

“No te preocupes,” her husband reassured her.

Construction work is steady, he said. Transportation and construction workers also accounted for nearly half of workplace deaths in the U.S. nationwide in 2020, per the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Then their physically intense labor was deemed “essential” and employees like Mendez were hailed as heroes by officials.

Words wouldn’t shield him from the virus infiltrating his lungs.

The sun sets behind Southwood, a 1,287-unit complex in South Richmond. Eight in 10 residents are Hispanic, with more than a quarter living in poverty. That's likely an undercount. SHABAN ATHUMAN/TIMES-DISPATCH

The first round of federal COVID relief funds for state and local governments to respond to the pandemic were in limbo through April and May when the General Assembly was unclear on how to distribute the money, couldn’t decide how to spend it and had to navigate limitations on its use.

Federal and state officials, The Times-Dispatch found, initially failed to give priority for protective masks or testing to front-line workers outside of those in health care settings, which had a greater chance of having access to gear and accurate COVID information than others in lower-income jobs — especially those not fluent in English.

Statewide messaging also didn’t consider basic facts for many working-class Latino families.

Officials said to socially distance when research showed Latinos immigrants were among the most likely to occupy crammed living spaces. They said to stay home when most blue-collar Latinos couldn’t. They said to speak to your health care provider when state data showed more than 40% of Latinos in Virginia reported not having one.

In Virginia and most states, there is still little-to-no public accounting of the more specific impact the virus had on workers in front-line occupations like Mendez, immigrants, disabled residents or people who aren't fluent in English. Richmond-area hospitals either do not track COVID deaths by language proficiency or do not publicly release the information.

But a Boston hospital found that early on in the pandemic, their non-English-speaking COVID patients were 35% more likely to die.

A state-ordered language access audit of Virginia’s agencies released in December 2021 detailed how nearly every state agency — including VDH and suppliers of critical services like rent relief or unemployment — said they could not meet the needs of people with limited English proficiency most of the time.

A 2004 legislative watchdog report and the December audit recommended the General Assembly pass a statewide language access policy to guide agencies through these decisions and prevent similar mistakes. The legislature rejected bills to adopt those recommendations in the 2022 session.

With more than one million people in Virginia estimated to speak a language other than English, “there was never any debate on whether we should communicate with non-English speaking communities or communities with limited English proficiency,” said Maria Reppas, VDH’s director of communications. Reppas was tasked with overseeing the procurement of translations alongside the agency’s health information team.

“It was more the mechanics of how to do it, who should do it, when and the frequency of those materials being translated,” Reppas continued.

Internal emails at VDH’s central office from the first month and a half after Virginia’s first case detailed a consistent scramble to keep up with translating the volume of materials as information kept rapidly changing. Oftentimes, the fastest option was to pull documents from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Spanish language materials couldn’t always be easily found on the VDH website, if at all. Neither could the other five most common languages in Virginia — prompting sharp criticism from organizations who took on the burden of translating information for their communities to ensure COVID information was getting out.

Members of the Virginia Latino Advisory Board said they were translating executive orders through May 2020. Sacred Heart Center, a Richmond nonprofit focused on Latino communities, was shifting money to call thousands of Latinos to share COVID updates and ask what they needed. Richmond’s Office of Immigrant and Refugee Engagement was translating local orders. Spanish radio was relaying information about school closures because at the time, most correspondence was in English.

Fuentes, who struggles to read in Spanish, turned to national Spanish media like Telemundo for coronavirus information and then later relied on community health worker Shanteny Jackson and medical interpreter Xiomara Vidal, the two VDH workers in Southwood who had spent years building trust among residents of the nearly 1,300-unit apartment complex.

They had helped Fuentes vaccinate her children. She had seen them transport residents to get groceries for their families, helped them pay their taxes and connected people to organizations for domestic violence survivors. But the misinformation moved faster than they could.

On April 15, 2020, Jackson emailed her supervisors at Richmond and Henrico’s health districts.

Residents worried the virus was spreading, she wrote, and they were unsure how to keep safe. They needed more resources, more information on how to protect their families. Richmond City Health District launched a testing event the following week, but Fuentes heard in conversations with her friends that being tested was painful.

So she never went.

Two weeks later, Oliver told reporters there wasn’t a “good breakdown” of COVID data available for Latinos. Fairfax Health District said laboratories weren’t consistently reporting it, but what the local health department had was Latinos accounting for 51% of infections.

Maria Fuentes warms tortillas on a gas stove in her home at The Communities at Southwood in Richmond, where she had found a "till death do us part" kind of love. Eva Russo/times-dispatch

By mid-May, Fuentes couldn’t taste what she was cooking. At first, she thought she forgot to salt the frijoles. Then a man she had given food to the week before couldn’t smell the meals Fuentes prepared for him, and her husband came home from work feeling feverish. Her headaches began coinciding with a heaviness in her body that wouldn’t subside.

She tried to self-medicate to alleviate the symptoms. Some Vick’s VapoRub underneath the nose. Hot tea to coat the throat. Soups to settle the stomach.

But every day she felt a little better, her husband kept getting worse. His feet swelled so much he couldn’t walk and his chest refused to take in a full breath of air.

Fuentes didn’t think the last time she would see him would be the day he entered Chippenham Hospital in May. They were meant to grow old together. They were meant to have more memories.

In one of his final voice memos to Fuentes, Mendez urged her not to give up on Southwood — to not let go of the apartment they built a life in. But the rent relief she was eligible for was only in English. When she called the line, speakers answered in English.

They still do.

She quietly sobbed as she recalled his words to a reporter and gripped the gold chain with an attached crimson pendant that used to be his. The inscription read, "el cuerno de la abundancia." The cornucopia of abundance — a symbol of peace and prosperity.

For the past year and a half, she's prayed for both.

Maria Fuentes holds a pendant that was her husband's. Yuki Mendez died of COVID-19 at Chippenham Hospital on July 28, 2020. He was 40. Photos by Eva Russo/Times-Dispatch

Virginia officials promised the data was driving the COVID response when the data was incomplete and relying on outdated and underfunded data systems that for at least a decade, local and state officials forewarned couldn't handle a public health crisis.

Without enough VDH workers available who knew how to trudge through what existed, delays on knowing where to marshal resources were predictably inevitable. Ethnicity and race, for example, were separated on a state level until June 15, making the statewide devastation on Latinos unknown for months.

Richmond and Henrico’s health districts, which is one of the most well-resourced local health departments in the state, had one full-time data person and one epidemiologist who spent roughly half their time dedicated to data analysis when the pandemic started.

And even then, local public health workers like Deanna Krautner, Richmond and Henrico’s chief operations officer, likened their ability to respond to “building the plane while we were trying to fly it at the same time.”

When little was known about the virus and even less was made public about where the virus was spreading, legislators called on VDH to expand its demographics data, publish infections by ZIP-code and list the outbreaks inside nursing homes.

Last year, then-state health commissioner Dr. Norman Oliver told The Times-Dispatch that he couldn’t stand up at a media briefing and say VDH only had four people working on this at the time.

“But that was the truth,” he said.

An indirect result of this means to this day, some of the best information in the months before June 2020 about what the impact on Latinos looked like lies in anecdotes from the people who were living through and responding to the panic on the ground.

More than 15 Southwood residents and community leaders recalled stories of employers telling workers if they stayed home, they’d be fired or not paid. Others were requiring a negative test to return to work when test results were taking weeks to arrive, making people avoid getting tested to dodge the possibility. Some testing sites were open only during work hours.

Church leaders told The Times-Dispatch of construction workers in their congregation being worried about crews from New York City joining Richmond and Chesterfield sites to help with staffing at the height of the early surge. Entire households were getting infected and wouldn't seek testing in fear of public charge — a Trump-era rule that threatened to affect the immigration process of any non-citizen who sought out public benefits — or misinformation around costs for uninsured people.

When the CDC arrived to Richmond to provide damage control of the severe infection rates among Latinos, CDC team member Francisco Ruiz said in a press release of their findings that, “Through our conversations with community members, it was apparent that the current political climate had a direct effect on health seeking behavior among Latino immigrants.”

“We learned that a hostile atmosphere around immigration and immigrants hindered health-seeking behaviors.”

The CDC did not make the response team available for interviews.

VDH officials were hesitant to talk about the influence of politics in public health, especially in a pandemic undermined by the Trump administration — a pattern public health historian Merlin Chowkwanyun said is common when funding streams rely heavily on the federal government and "can be jeopardized if one is a little too overly critical."

But in State Board of Health meetings, some board members grew increasingly concerned with how little support public health seemed to receive in the then-Democrat-controlled state legislature, noting how without them, overcoming the pandemic would be near impossible.

Maria Fuentes shows reporters photos of her husband in her home in the Communities at Southwood in Richmond, Va on March 9, 2008. Fuentes lost her husband to Covid-19 on July 28, 2020. EVA RUSSO/TIMES-DISPATCH Eva Russo

“I reached out to a number of legislators on both sides, asking them to be particularly supportive of what we as a Board were recommending, and I didn’t get much response,” said Board of Health member Jim Edmondson in a Sept. 3, 2020 meeting. “We need some help. We need some champions in the legislature. And at the moment, I don’t think we have them.”

It's been almost two years since Fuentes last held her husband's hand. Sometimes she still reaches for it.

Sometimes she peeks out the door at 5 p.m. when the construction crews start arriving home as if he'll be among them. Sometimes she looks over her shoulder after flipping tortillas on the comal at dinnertime as if he's sitting in the high-top dining chair ready to make her laugh again.

Instead, there's only the reminder of the virus that killed him.

On a recent Wednesday morning, Fuentes took out a stack of photos she hasn't looked at since the month before he died. He loved documenting everything, she said. The stills depicted a grinning 19-year-old Mendez with the world ahead of him — at Libby Hill Park. In front of his first Southwood apartment. Beside his three children.

Fuentes wishes she could tell politicians how it didn't have to be this way — that another world is possible.

"And we deserve to see it."

Reporting for "Essential and Overlooked" was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2021 National Fellowship and the Dennis Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

[This article was originally published by Richmond Times-Dispatch.]