Hazardous Homes

This story is by Angela Caputo of APM Reports, a 2020 National Fellow, and Sharon Lerner of The Intercept.

Gerica Cammack near her home in North Birmingham, Ala.

Photo: Andi Rice for The Intercept

IN SOME WAYS, they couldn’t be more different. Gerica Cammack is a Black woman from Alabama; Floyd Kimball is a white man from rural Idaho. Yet they’re facing a similar ordeal. They’re both single parents, forced by difficult circumstances to live in government-subsidized housing surrounded by pollution that is, or could be, poisoning their children. Like tens of thousands of people across the country, they live near, or on, some of the most toxic places in the nation. And the government has failed to protect them.

In 2019, Cammack moved into the Collegeville Center, a public housing complex in north Birmingham, Alabama. She knew that moving into the neighborhood came with risk. The complex sits near a bevy of industrial sites that produced steel and iron and spewed pollution over nearby residents for decades. She’d lived up the road years earlier and remembered how the fumes could be so overwhelming that the taste of them would linger in her mouth. But she was pregnant, homeless, and grateful for the apartment, so it was a danger she had to face.

Little did she know that the Environmental Protection Agency had classified the area as a Superfund site, signifying that it was one of the most polluted places in the country. Testing had found the soil in her housing complex contaminated with lead, arsenic, and other carcinogens.

More than 2,000 miles away, Kimball and his 4-year-old son live on a Superfund site as well. The federally subsidized apartment complex in Wallace, Idaho, they moved into three years ago, after Kimball lost his job, sits on one of the largest Superfund sites in the country. Though pollution from heavy metal mining was documented decades ago, neither the local nor federal government has moved people from dangerous conditions or sufficiently clean up the contamination. Meanwhile, many residents, including Kimball’s young son, have been exposed to dangerous amounts of lead. Kimball’s 4-year-old son hasn’t yet begun to speak.

An EPA analysis obtained by APM Reports and The Intercept found that more than 9,000 federally subsidized properties — many with hundreds of apartments or townhouses — sit within a mile of Superfund sites. Those properties are in 480 cities in 49 states and territories. But even that is an undercount. The list of 9,000 properties doesn’t include several subsidized-housing complexes within a mile of Superfund sites.

In most cases, the federal government has chosen not to relocate housing complexes near Superfund sites and made only piecemeal attempts to address the health threats. Housing officials often don’t inform people who move into these housing complexes that a Superfund site is nearby. Neither the EPA nor the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the two federal agencies primarily responsible for protecting residents, regularly monitor the potential health threats to residents from nearby environmental pollution. In fact, some housing complexes near Superfund sites haven’t been tested for contamination in years, according to the APM Reports and Intercept investigation. Even when testing is conducted and dangerous contamination is found, the pollution isn’t always cleaned up.

As a result, thousands of residents continue to live in places that are potentially dangerous to their health.

The problem is rooted in a history of the federal government developing public housing on cheap land in industrial, polluted areas. The approach was summed up in 1966 by Benjamin Lesniak, then executive director of the East Chicago Housing Authority in Indiana, when he noted the city’s lack of available land for new public housing and floated a possible solution. “We can build them in vacant areas that are surrounded by industries,” he said. Lesniak went on to oversee the construction of a housing complex on the site of an old copper smelter and a lead refinery in the city. (The complex was emptied in 2016 after residents were exposed to elevated levels of lead and arsenic for decades.)

Floyd Kimball and his 4-year-old son Steve in Wallace, Idaho, on Jan. 5, 2021. They have lived in public housing located on the Bunker Hill Superfund site for four years. Photo: Rebecca Stumpf for The Intercept

Experts say many of the communities identified by APM Reports and The Intercept likely couldn’t be built today in their current locations under state environmental regulations enacted after the EPA was created in 1970. Nearly a third of the roughly 9,000 public housing properties flagged by the EPA for their proximity to Superfund sites were built before environmental assessments were required under federal regulation.

The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act — commonly known as the Superfund law — passed in 1980 established a program under the EPA to clean up some of the nation’s most polluted sites and hold corporations accountable for their environmental messes. A tax on polluters funded the program in its early years, but it expired in 1995. Since then, the government has had to pay for these massive cleanups, many of which have stalled because of funding shortages.

The residents — many of whom can’t afford to live anywhere else — are left in a bureaucratic gap between various governmental agencies that lack the authority or resources to directly address the problem. The EPA and state environmental agencies have struggled to clean up Superfund sites and, in many instances, can’t confirm that they’ve contained the threat to human health. Local housing authorities lack the money to address pollution or test for contaminants, and it’s rare for the Department of Housing and Urban Development to analyze the health risks or relocate people from hazardous housing complexes despite its own regulations requiring the agency to provide tenants with a safe and healthy place to live.

Nearly a third of the roughly 9,000 public housing properties flagged by the EPA for their proximity to Superfund sites were built before environmental assessments were required under federal regulation.

The problem is well known to housing officials. The inspector general’s office that monitors HUD requested money in its 2020 annual budget to investigate the threat to public housing residents from Superfund sites, writing in its request, “The dangers posed to HUD programs by inadequately responding to this looming risk of unsanitary and unsafe housing are incalculable.”

Following the East Chicago crisis, EPA and HUD officials agreed to meet quarterly to share information and address housing sites where there was concern about residents’ health, according to a document from an early meeting between the two agencies in 2017. Among the goals of the collaboration was to “coordinate communications with public housing residents.” The EPA contends that it communicates with residents who live near Superfund sites. “Notification to the community would occur, at a minimum, when a site is proposed and listed [as a Superfund site], and community involvement activities would continue throughout the cleanup process and be tailored to meet community needs,” an agency spokesperson wrote in an email.

Superfund cleanups can take decades, though, and residents who move into a complex are often not informed of the nearby pollution. “Sometimes people know anecdotally,” said Michael Kane, executive director at National Alliance of HUD Tenants, “but most of the time people that live on toxic sites don’t know their kids are going out and playing on contaminated land, with lead and other toxins.” Those who do know about the contamination receive little guidance from the government aside from general tips from health and environmental officials, such as monitor children so they don’t eat soil and don’t chew gum while gardening.

Eugene Goldfarb, a retired HUD official who oversaw the implementation of environmental regulations dating back to the EPA’s earliest days, cautions that “just because there’s contamination on the property doesn’t mean that there’s a pathway to adversely affect health and safety. That’s an important distinction.”

But hundreds of documents — including environmental assessments and reports drawn up by private consultants and government officials across the country — gathered by APM Reports and The Intercept reveal for the first time what’s known about environmental hazards at public housing properties, which are occupied disproportionately by children, the elderly, and disabled people. Combined, the records show a troubling pattern, much like the one in Birmingham and Wallace, where people have been left exposed to hazardous conditions even years after the EPA or state officials found nearby pollution.

The few checks created by HUD often fall short. While local and federal housing officials are supposed to provide a safe environment, they aren’t required to test to determine if environmental hazards pose a threat to human health. In fact, federal and state regulations typically require housing officials to test for contaminants primarily in one circumstance: when they are seeking money to redevelop or improve a property. It’s a system that critics say prioritizes shielding lenders and developers from liability over residents’ health.

Robert Weinstock, an attorney with the University of Chicago’s Abrams Environmental Law Clinic who recently co-authored a report on subsidized housing near toxic sites, said the problem is that a number of government agencies on the local, state, and federal levels are involved and none of them have taken decisive action to protect residents’ health. “Who is responsible?” Weinstock said. “Everyone and no one at the same time.”

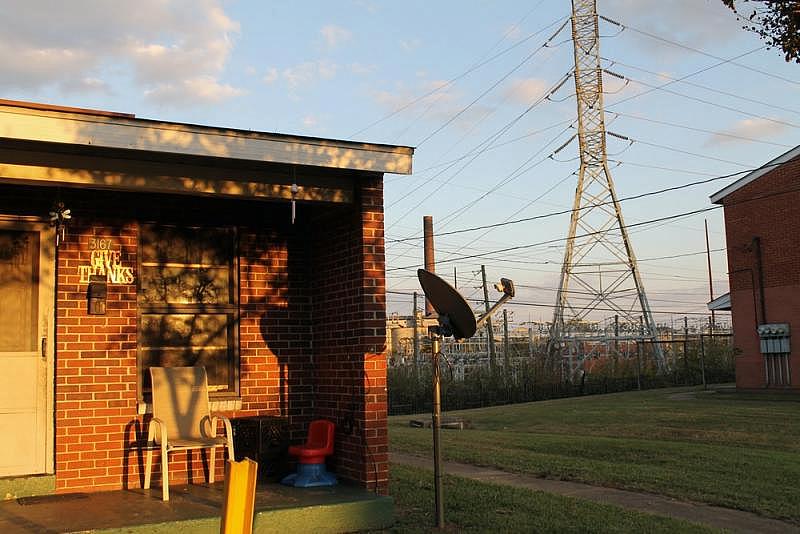

The view from a housing complex in North Birmingham, Ala. In the 1960s and ’70s, the Housing Authority of the Birmingham District built hundreds of public housing units for Black families in the most polluted part of the city. Photo: Miranda Fulmore for The Intercept

A City of Iron and Steel

Since its founding in the years following the Civil War, Birmingham has been a center of steel and iron production. And the Collegeville Center public housing complex on the city’s north side, built in 1964 on the edge of a pipe foundry, is surrounded by facilities that have fueled those industries.

The neighborhood faces a toxic threat both past and present. Poisonous remnants of heavy metal production at facilities long since closed — carcinogens like lead and arsenic — lace the soil. But there is also pollution that is ongoing and severe.

Today, the census blocks where the Collegeville Center sits in North Birmingham are subject to more dangerous emissions from local factories than 95 percent of census tracts nationwide, an analysis of EPA data shows. The area’s toxic concentration scores — a measure of chemical releases weighted by toxicity — are three times higher than the citywide average. The top polluters, according to EPA data, are two facilities that produce coke, a fuel derived from coal that’s used in the smelting of iron ore, and a steel plant. They have long been under scrutiny for dangerous emissions.

In 2018, the year before Gerica Cammack moved in, Birmingham Mayor Randall Woodfin sounded the alarm about Collegeville Center when he warned the EPA’s top administrator that “thousands remain at risk including the 1,070 people living in 394 public housing units and 751 children attending Hudson K-8 school.” Cammack knew there was pollution nearby, but she had little way to know how bad it was. And toxic chemicals in the air weren’t her top concern at a time when she was so broke that she slept on the floor.

Like many residents in North Birmingham, she had come to think of pollution as simply a fact of daily life. People have long adapted by closing windows or taking laundry off the lines when the air grew thick with ash or smog. They grew up in it, worked in it, ate in it, and played in it.

After moving in, Cammack, 27, tried to make a home for herself and her daughter, who is now 15 months old. Cammack’s grandmother taught her to garden when she was growing up, and it always lifted her spirits. But when she tried to grow flowers outside her apartment, nothing would take in her front or backyard. She blames the soil’s infertility on the pollution that’s hung in the air and sunk into the ground in North Birmingham for as long as she can remember.

Like many residents in North Birmingham, she had come to think of pollution as simply a fact of daily life.

In the 1970s, Cammack’s mom, aunts, and grandparents lived in the nearby North Birmingham Homes, a public housing complex less than a half-mile from Collegeville Center. The developments are divided by an area zoned for heavy industry and includes a metals scrap yard, a foundry, and a coke plant.

As in North Birmingham, where most residents are Black, the environmental burden from Superfund sites across the country falls disproportionately on people of color, who are also overrepresented in public housing for families. In the 1930s, public housing was built for people of all races temporarily laid low by the Great Depression. But over the years, the proportion of residents who were Black and Latinx grew. “Because of housing segregation and housing discrimination, in many cases across the country, low-income whites were better able to escape this housing,” said Robert Bullard, an advocate and scholar who is sometimes called the father of the environmental justice movement. “People of color were more likely to be stuck in these areas with high concentrations of pollution.”

Gerica Cammack has tried to make a healthy home for herself and her daughter despite the environmental hazards that surround them in North Birmingham, Ala. Photo: Andi Rice for The Intercept

Unbeknownst to Cammack, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, an arm of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, had issued an alarming assessment of the community that includes Collegeville Center in 2017 that “daily exposure to soil at properties with elevated lead concentrations could have in the past and could currently be harming their health,” particularly children.

That report was based, in part, on soil testing that the EPA conducted throughout the neighborhood between 2012 and 2014 that found dangerous amounts of lead and the carcinogen benzo(a)pyrene in more than a dozen samples taken from the Collegeville Center alone.

Benzo(a)pyrene is a chemical byproduct of coal when it’s cooked to produce coke for processing iron and steel. Long-term exposure to benzo(a)pyrene is linked to lung, stomach, and skin cancer. It’s also proven to cause miscarriages and birth defects in lab animals. Lead exposure can cause permanent brain damage, and children and pregnant women are most susceptible.

Cammack had no idea that the soil around her home had a history of contamination and, like the parents of 90 percent of the other young children who live in Jefferson County, never got her daughter tested for lead exposure.

The EPA began investigating the area back in 2009. Eventually the agency drew the Collegeville Center, North Birmingham Homes, and several industrial facilities into an area deemed the 35th Avenue Superfund site. By 2014, the EPA proposed adding it to the National Priorities List, which gives areas preference for further investigation because of known or threatened releases of hazardous substances. But that effort was beset by controversy, and even after years of study and remediation, people are still exposed to dangerous soil and air emissions.

There’s been so much industrial churn in North Birmingham over the past century that the EPA can’t pinpoint the exact source of the contamination. By the agency’s calculation, the area has featured at one time or another: 20 foundries and kilns; seven coal, coke, or byproducts facilities; 26 scrap and metal processing plants; and four chemical plants. Many of the companies went out of business in the late 1970s and 1980s, according to a city planning document, when enforcement of environmental regulations started to cut into profit margins.

A coal executive hatched a secret scheme to keep the 35th Avenue site off the National Priorities List to avoid cleanup costs.

The EPA’s investigation and testing found high levels of air pollution and, in 2014, the agency assigned the 35th Avenue site the maximum score for likely soil exposure by residents under the Hazard Ranking System, the scorecard for determining eligibility for the National Priorities List.

But an executive from Drummond, a coal producer that owns the nearby ABC Coke plant named as one of the potentially responsible polluters, hatched a secret scheme to keep the site off the National Priorities List. He and a lawyer representing the company were eventually criminally charged with quietly leading an effort to get local, state, and federal elected officials, including Alabama’s attorney general, to oppose the additional oversight. The scheme became public and ended in scandal. A state representative and a regional EPA administrator pleaded guilty to criminal charges as well.

The map shows the 35th Avenue Superfund site in North Birmingham. The Collegeville Center and the North Birmingham Homes both are within the boundary of the Superfund site, an area that’s endured industrial pollution for years. Though the EPA says the area is cleaned up, the agency’s own records show that there are still toxic chemicals in the area. The map may not have the full extent of the Superfund location. Map: APM Reports, The Intercept

Though the scheme was exposed, the 35th Avenue Superfund site wasn’t added to the priorities list. While the corruption and political drama initially drew more attention to the neighborhood’s problems, Haley Colson Lewis, an attorney with GASP, a local environmental advocacy organization, said the momentum for getting the site on the National Priorities List has since stalled.

The EPA did conduct an initial cleanup of the Superfund site and the neighborhood, but records obtained by APM Reports and The Intercept show that environmental officials knew residents would likely continue to face health dangers from ongoing pollution. The EPA warned in 2011 that dangerous ash would only continue to migrate from the coke plant that sits less than 3,000 feet away from both public housing complexes. “The surrounding community will continue to experience deposition from the plant unless controls are put in place,” the EPA’s on-scene coordinator wrote in a memo to his peers as they prepared to expand testing and cleanup in the area.

The agency has since shifted its stance. EPA officials now say they believe, based on a few samples from the surrounding neighborhood, that contaminated dirt brought in from nearby industrial sites is to blame for much of the pollution; they still maintain that the public housing is clean.

EPA records show that during the 2014 cleanup of the public housing, the agency left in place lead, arsenic, and benzo(a)pyrene in some areas because the pollution didn’t exceed the level that would trigger removal. The agency hasn’t conducted significant soil testing at the housing complexes in six years.

The current hazards in the soil at the housing complexes are unknown; the agency hasn’t conducted significant soil testing at the housing complexes in six years.

Rep. Terri Sewell, a Democrat who represents North Birmingham in Congress, said the only way residents can rest assured that they are safe is if federal and local officials’ oversight is vigilant. “This problem didn’t happen overnight,” she said. “It’s not going to be solved overnight.”

Residents have come to distrust government pronouncements about the safety of the area. That’s in part because whenever the EPA has conducted environmental testing in the past decade, the results show pollution levels worse than people were led to believe. For instance, following the first tests by the EPA back in 2009, when dangerous levels of the benzo(a)pyrene and arsenic were found at two elementary schools that sit next door to each of the public housing complexes, the area was cleaned up and given the all-clear. Based on those limited results, the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry concluded exposures to soil in the area “do not present a public health hazard.” That conclusion would be proven false when the EPA soon found further contamination in the area that led to the 2014 cleanup.

The fact that the EPA can’t confirm health risks have been eliminated at the 35th Avenue Superfund site or the surrounding area — which includes two coke plants, asphalt batch plants, pipe manufacturing facilities, steel producing facilities, quarries, and a coal gas holder and purification system facility — has led to distrust among residents and environmental activists.

Charlie Powell, an activist with the local environmental justice group People Against Neighborhood Industrial Contamination, or PANIC, wonders how officials consider the site cleaned up with so much pollution still spewing over the community. “How can you say it is not going to happen again, but the plants are still doing the same thing?”

After the EPA named ABC Coke one of the potentially responsible parties for contamination across the 35th Avenue site, an executive from Drummond, which owns the plant, hatched a plan to shield the company from liability. Photo: Andi Rice for The Intercept

Opening Pandora’s Box

Activists like Powell believe that residents should be moved out, and the area should be rezoned for industrial use only.

The Housing Authority of the Birmingham District may have other ideas. In a 2018 planning document, the housing authority notes that it would like to redevelop the North Birmingham Homes, which, like the Collegeville Center, also have “widespread environmental issues.” Using public money to redevelop the property would require thorough environmental reviews. And therein lies an irony, critics note.

Some of the same public housing properties that haven’t undergone a thorough environmental assessment in years, despite their proximity to a Superfund site and large amounts of pollution, would be studied to pave the way for a redevelopment project.

“It’s a process to protect projects, not people.”

“It’s a process to protect projects, not people,” said Weinstock, the Abrams Environmental Law Clinic attorney.

Such environmental reviews of polluted properties sometimes turn up more toxic pollution than anyone was expecting. That’s what happened in Anniston, Alabama, which lies 50 miles east of Birmingham. The local housing authority opened Pandora’s box when it attempted to rebuild three of its largest public housing complexes near the Anniston PCB — polychlorinated biphenyl — and Lead Superfund sites.

As in Birmingham, numerous officials had claimed over the years that the site had been cleaned up and the housing complexes were safe. But when consultants conducted the environmental review, they found traces of PCB, lead, and industrial fill on three separate sites where families lived for years.

APM Reports and The Intercept collected similar environmental reviews from 75 properties clustered around Superfund sites across the U.S. and found that consultants flagged chemicals and toxic waste — including lead, arsenic, chromium, and PCB — at half the properties. In other cases, the findings were inconclusive, the inspections were only visual, or consultants cleared the properties based on data provided by companies that would have to pay for remediation.

In Anniston, the EPA gave the properties a clean bill of health years ago and, like most of the public housing that sits within a mile of a Superfund site, they passed HUD’s health and safety inspections repeatedly. That’s because HUD’s inspections look for building-related hazards like lead paint and asbestos but not environmental threats. The consultants’ conclusions only affirmed the suspicions of David Baker, a local environmental activist who sits on a local Superfund advisory committee, that more cleanup is needed.

Baker spent the past couple of years trying to get a fence put up around one of the last parts of the community to be cleaned up, a PCB-contaminated stretch of Snow Creek that runs along the north east corner of the Glen Addie apartments where kids play, trying to catch fish, turtles, and tadpoles. The housing authority had big plans to modernize the complex, but the problems revealed in the environmental testing, Baker said, only affirms what he’s been saying all along: “Anniston needs to be retested.”

Meanwhile, only one of the public housing redevelopments is moving ahead. The other two are still on hold.

The Lower Burke Canyon Repository on the Bunker Hill Superfund site, seen across the street from Canyonside Townhouses. Photo: Rebecca Stumpf for The Intercept

Living on Idaho’s “Megasite”

Floyd Kimball’s son, Steve, was just 7 months old in 2017 when the two moved into Canyonside Townhouses in Wallace, Idaho, which sits on the massive Bunker Hill Superfund site. Floyd, who had recently lost his job as a cook at a resort, was relieved to find an affordable two-bedroom. And he and his son, a happy and playful toddler, quickly settled into their new home. But even as Steve thrived in some ways, he began to lag in others. At 2 years old, he didn’t talk or babble the way other toddlers did, which worried his father.

Last year, Floyd brought Steve to a pediatrician who tested his blood and found elevated levels of lead. Afterward, Floyd called the local health department, which then tested for lead at Canyonside Townhouses in July 2019. The results pointed to the source of the boy’s elevated blood lead level — or, rather, to several sources.

Lead, a heavy metal associated with speech delays and other developmental problems, was detected in the dust on Floyd’s boots; on the gray couch where Steve often colors and watches cartoons; on the stairs leading up to the boy’s bedroom; and in several areas on the property where he and other children in the complex often played, including on the playground equipment, in the sandbox, and on a nearby hillside.

A specialist with the local health department also measured lead on Floyd’s car keys, which Steve liked to put in his mouth at the time. The level of lead on the keys was 1,110 parts per million, almost three times the safety threshold the agency set for soil. In a vacant field across the road from the apartment complex, a former mining spot where Steve and other children play, lead was measured at 19,810 parts per million: almost 50 times the action level that would trigger a federal cleanup.

APM Reports and The Intercept hired contractors to conduct independent testing at three federally subsidized housing complexes on the Bunker Hill Superfund site, where decades of heavy metal mining contaminated a huge area. The results confirmed the presence of lead in house dust — the best predictor of blood lead levels in children — at each of the complexes.

An empty field and a playground at Canyonside Townhouses, seen on Jan. 5, 2021, is the primary area where children of the public housing complex play in Wallace, Idaho. Photo: Rebecca Stumpf for The Intercept

In the Amy Lyn Apartments, a subsidized family complex in Kellogg, Idaho, just a short drive from the Kimballs’ apartment, lead was found on the laundry room floor. Though the EPA doesn’t have a cleanup level specifically for laundry rooms, the level of the neurotoxin was more than 13 times higher than the actionable levels for the floors of apartments, according to analysis of samples conducted by American Scientific Lab, an EPA-approved independent lab hired by APM Reports and The Intercept.

In the nearby Shoshone Apartments, the APM Reports and Intercept testing discovered lead in the corner of an apartment floor, where a children’s scooter and toys were stored, in an amount above a safety level set by the EPA.

In an email, a spokesperson for the local housing authority emphasized the agency’s concern for the health and safety of residents of the Shoshone Apartments and noted that the complex underwent extensive remediation in 2002 and an environmental review in 2015.

At Canyonside, lead was detected above EPA’s safety threshold for apartment floors on the playground and on the floor of Kimball’s apartment. (The EPA does not have a standard for playground floors.) For Floyd, the presence of lead in the samples was devastating but not surprising. From his apartment window, he regularly sees heavy machinery moving contaminated earth.

In most places throughout the country, the presence of lead at such levels would trigger immediate action. But in these three federally supported housing complexes, the heavy metal is allowed to be present at significantly higher levels because they are on Bunker Hill, one of the largest Superfund sites in the U.S.

The Canyonside complex, 24 apartments arranged into three neat rows set in a woody hillside, was built in 1982, after a century of metal mining had turned the surrounding area of north Idaho into one of the most polluted places on Earth. The complex was finished just a year before the EPA first deemed a 21-square-mile area around the Bunker Hill mine a Superfund site. Though some environmental experts felt the only safe solution was to move the residents from the area, this was never done.

The area was once the largest silver-producing region in the world. Bunker Hill was the largest lead and zinc mine in the U.S., and the Bunker Hill lead smelter was also the nation’s largest. The industry left behind more than 100 million tons of mine waste — including aluminum, antimony, arsenic, cadmium, iron, manganese, zinc, and lead — much of which was dumped into local rivers and streams. Trees couldn’t grow in the metal-laden soil. Fish disappeared from the waters. Livestock routinely grew sick and died. And local residents experienced brain damage on a massive scale.

Young children like Steve are the most vulnerable to the effects of lead. Today, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recognizes that no level of lead is safe, while setting 5 micrograms per deciliter of blood as the level at which “public health action” should be taken. In 1976, after a smelter fire caused the largest lead poisoning event of children in U.S. history, the mean blood lead level of children living nearest the Bunker Hill smelter was 68 micrograms per deciliter — more than 13 times the current threshold, according to “Living With Lead,” a book about the environmental history of the mining area.

Concerns about the lead poisoning of Kellogg’s children helped fuel the 1983 decision to designate Bunker Hill as one of the nation’s first Superfund sites. At the time, the Superfund program was still paid for by the tax on polluting industries, which was fortunate since by then both the Bunker Hill Mine and Gulf Resources & Chemical Corp., which had bought the mine years earlier, had declared bankruptcy. In 1998, the site was extended to include the area surrounding the “box,” as the original site is known. The whole site — or “megasite,” as the EPA calls it — is now larger than Delaware.

In 2005, a National Academy of Sciences report on “Superfund and Mining Megasites” predicted that the cleanup of Bunker Hill, which had already been underway for more than two decades and cost hundreds of millions of dollars, would take centuries more and additional hundreds of millions of dollars to remediate — and even then the area would remain polluted.

Floyd Kimball outside his home in Wallace, Idaho, on Jan. 5, 2021. Photo: Rebecca Stumpf for The Intercept

Nuclear Weapons Against BB Guns

The Superfund program, one of the federal government’s most ambitious environmental efforts, has struggled financially and politically amid ongoing budget cuts. Though the EPA works hard to get companies to cover some of the costs of cleaning Superfund sites, “they’re never covering the actual cost of the damage they caused,” said Joel Hirschhorn, who spent much of his career working on Superfund issues, both through the Office of Technology Assessment — which advised Congress on scientific issues — and as an independent environmental engineering consultant.

While the Trump administration has claimed success in the Superfund program, pointing to its role in the cleanup of 27 polluted sites, Jim Woolford, who was director of the EPA’s Superfund program from 2006 until retiring last April, disputed that characterization. Woolford said some of these sites were cleaned up by previous administrations and pointed out that there is a long list of sites awaiting cleanups that have yet to be funded.

“The backlog is a train wreck that has been long in the making,” said Woolford, who estimates that the cost of fully remediating the sites awaiting cleanup to be between $750 and $850 million. “I was forthright with the [Trump] administration about needing more money, and they just pushed back and said ‘you’re not going to get it,’” he said.

In part due to this lack of funding, most cleanups are only partial. “Between 80 and 90 percent of our sites leave some contamination in place,” Woolford said.

The Superfund program’s struggles are especially evident at Bunker Hill. The massive amounts of pollution made cleanup extraordinarily challenging, and the powerful local mining industry made it harder still, said Hirschhorn, who worked on dozens of Superfund cleanups. “They fought against better testing of blood in kids, better testing of lead in soils. They were just against protecting public health and safety.”

The result, Hirschhorn said, was a “failed remedy” that resulted from the government’s inability to stand up to industry. “EPA didn’t stand a chance. They didn’t have good enough staff or the political leadership willing to go against the major corporations.” He described the power mismatch between the agency and mining companies as “nuclear weapons against BB guns.”

With residents still potentially exposed to dangerous heavy metals, government officials are relying on long out-of-date health standards. And they’re not monitoring the health of all children in the area.

A map of the area surrounding the Canyonside apartments that the Panhandle Health District sent Floyd Kimball along with test results showing the presence of lead in his home. Map: Panhandle Health District

More than 7,100 yards and public spaces have been cleaned up and 581 roadway segments recently paved at the Bunker Hill site, work that an EPA spokesperson described as “dramatically reducing people’s exposure to lead and other metals.” But other goals remain unmet. And at least two of them — the cleanup threshold for soil and the children’s blood levels noted in the site’s “remedial action objective” — are dangerously out of date. In 2012, the CDC lowered the blood lead “level of concern” nationally from 10 to 5 micrograms per deciliter. But the Bunker Hill site has yet to update its objectives to meet those standards. Instead, the EPA’s official “remedial action objective” for the site, which was created in 1991, requires that less than 5 percent of children tested for lead have blood lead levels above 10 micrograms per deciliter without specifying how many children overall should be tested.

The National Academy of Sciences committee recommended universal blood lead screening of children between ages 1 and 4 on the Bunker Hill site. But that hasn’t happened. While there is no question that children’s blood lead levels have steadily fallen in the area since the worst of the pollution crisis, lead exposure persists and some children are still falling through the cracks.

In 2019, the most recent year for which data is available, only 169 children under 6 living within the bounds of the original site had their blood tested for lead, according to the Panhandle Health District. Eighty-two of these children were found to have lead in their blood; 23 of them had blood lead levels above 5 micrograms per deciliter — the current level of concern identified by the CDC. Eight children had blood levels above 10 micrograms per deciliter. And two had levels above 20, a level at which children begin to experience irritability and loss of appetite.

Lasting neurological damage can occur at levels well below the 5 micrograms per deciliter set by the CDC or even the 10 micrograms per deciliter used in Bunker Hill. An increase in children’s blood lead level from less than 1 to 10 micrograms per deciliter was associated with a 6-point drop in IQ score, according to a 2005 study in Environmental Health Perspectives. But it’s impossible to know how many children living on the Bunker Hill site are exposed or had lasting neurological damage because some aren’t tested.

In 2016, 2017, and 2018, fewer than 150 children in the center of the site had their blood tested for lead each year. Among those who were tested, a significant minority had blood levels above the current safety threshold. The 125 children under 6 tested in the box in 2017 likely represented about half of the children in the area, said Andy Helkey, Kellogg Remediation Program Manager at the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality.

Helkey said that the blood testing results showed that Bunker Hill technically met the EPA’s objective for the site of having less than 5 percent of children with blood lead levels above 10 micrograms per deciliter. But he acknowledged that some individual communities within the Superfund site didn’t meet that almost 30-year-old goal. And many children in the area still haven’t been tested.

Though the EPA and companies responsible for the pollution in Bunker Hill have already spent more than $1 billion cleaning up the site, the health department lacks the money to determine how many children live in the epicenter of the Superfund site and to test them, Helkey said.

Meanwhile, the level of lead that triggers remediation at the Superfund site — 1,000 parts per million, which was set in 1991 — is more than twice the level that the EPA set for residential soil in the rest of the country: 400 ppm. So when local health officials found lead present at 401 parts per million on the decking of the playground at the Canyonside complex, they weren’t legally bound to remove it. Asked about the discrepancy, an EPA spokesperson wrote in an email that the agency “is considering various options to accelerate protective and efficient Superfund residential lead cleanups.” The spokesperson also acknowledged that individual sites may have different cleanup levels for lead that depend on “site-specific conditions, such as the degree to which lead is bioavailable.”

There’s little question that many people living on Bunker Hill are suffering from lead exposure. “Pretty much everyone I talked to in a long-term family had long-term health problems,” said Sue Moodie, an epidemiologist and health researcher who spent several months interviewing residents in 2008 and 2009. “There were a lot of reports of children getting really frustrated in school and having behavioral problems and breaking things.”

For Kimball, the revelations about the likely sources of the lead in his son’s blood haven’t helped him prevent further exposure. After he received the test results from the health department, Kimball said he asked the building management to address the problem, but no action was taken. “I talked to everyone I could possibly talk to, but nobody seemed to want to do anything,” said Kimball, who keeps a thick file of his letters seeking help about lead.

The local health department was also of little help. Valerie Wade, an environmental health specialist with the agency, suggested that Canyonside Townhouses install additional play areas on site so that the children in the apartments would be less likely to go to the highly contaminated lot across the street, according to a health district spokesperson, who said that “the apartment complex said they did not have funding to do so.”

Wade explained the situation this way to Kimball in an August 2019 email: “Unfortunately, we cannot force them to do anything,” she wrote, going on to encourage Kimball to “steer clear of the contaminated areas and get inventive with things to do with” your son.

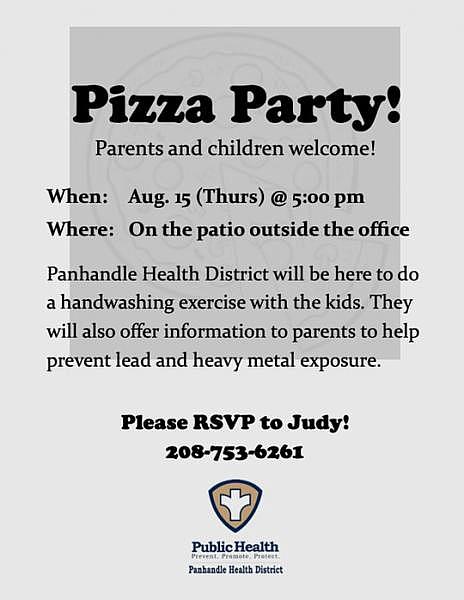

Although the local health department did not remove lead from the apartment complex, it did hold a pizza party at which children were encouraged to wash their hands. Flyer: Panhandle Health District

While the local health department didn’t substantively address the immediate lead threat facing Steve Kimball at Canyonside, federal agencies were aware that something could and should be done to address the environmental risks facing residents of subsidized housing on Bunker Hill. At a November 2017 meeting between HUD and EPA officials, Bunker Hill was one of the first sites mentioned, with at least one meeting attendee noting that human exposure was not under control at the site. At the meeting, the agency staffers spoke hopefully about future conversations about Bunker Hill and their plans to share maps and other information with other agencies.

But three years later, the lead contamination persists. Kimball is still waiting for help, and his son, now 4 years old, still hasn’t begun to speak.

While the area seems to have faded from the EPA’s attention, Kimball thinks about the pollution he and his son must confront every day. “It pops into my head every time I go outside,” he said.

A Legacy of Activism

On a recent afternoon, a team of scientists and environmental activists met around the corner from the Collegeville Center in North Birmingham to hang air monitors that will gather independent evidence about what exactly residents are still being exposed to.

GASP, the local environmental justice organization spearheading the effort, already conducted one round of testing, in 2020, that found concentrations of naphthalene, a carcinogen produced in coal and petroleum processing, at up to 50 times the EPA’s cancer risk level. They also found concentrations of benzene, another known carcinogen, up to 29 times the EPA’s cancer risk level.

The group plans to use the data from air monitoring to continue pressing the EPA to place the 35th Avenue Superfund site on the National Priorities List, which would bring additional funds for testing and cleanup.

GASP’s attorney Colson Lewis said the group is motivated in large part by the children always playing outside at the public housing complexes oblivious to the risks they’re being exposed to. “It just makes you want to keep advocating for what’s best for everyone’s health,” she said, “especially the children who can’t do it for themselves.”

There’s a rich history of activism in the area. The Collegeville housing complex sits just down the block from the famed Bethel Baptist Church, where Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, a co-founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, was the longtime pastor.

Five decades ago, city planners noted that “smoke, noise, and fumes from heavy industries and railroad operations and truck traffic permeate the area” around the Collegeville Center. The same conditions exist today in North Birmingham, Ala. Photo: Andi Rice for The Intercept

Cammack’s grandfather followed in a long tradition of men before him who, despite the power of the community, faced continued obstacles. After he worked for years in a local quarry, his health began to fail. He was compensated, and the family used the money as a down payment on a house. While home ownership became a point of pride for the family, Cammack said, “he paid with his life.”

So she’s taking extra precautions to protect her daughter. Cammack takes her to play at a park farther from their apartment complex, but the smoke plumes and foul smell tend to migrate, and she often cuts the trips short.

“It’s alarming,” Cammack said. “You can see it and smell it, but it’s hard to know how it affects you.”

Local environmental activists continue to push for federal oversight through the Superfund program, which would bring more money to repair the community. And they’re optimistic that incoming leaders at the EPA and HUD will make oversight a priority.

How much of a priority remains to be seen. “Everything is a balancing act,” Goldfarb, the retired HUD official, said. With resources scarce and the federal deficit growing, he said, “The question is what are we going to spend money on?”

Will Craft contributed reporting and data analysis for this story.

Support for this project was provided by the University of Southern California’s Center for Health Journalism.

[This story was originally published by The Intercept.]

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.