How did some Rochester neighborhoods become greener than others?

This story was produced as part of a larger project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 Data Fellowship.

Other stories by Justin Murphy include:

This project mapped every tree in Rochester. Here’s how we did it

‘I now see the disparity is real.’ For Rochester’s mayor, trees are a justice issue

Rochester’s trees are celebrated, but not everyone gets to have their time in the shade

Walk through Rochester's Washington Grove, a rare remnant of nation's old-growth forests

Sign up to learn about Rochester's trees by texting with reporter Justin Murphy

Tell us the story of your favorite tree in Rochester. Where is it and why is important?

Read about Rochester’s most beloved trees and share your own story

Rochester's trees make Landmark Society of Western New York's annual 'Five to Revive' list

Democrat and Chronicle

The basic itinerary in Rochester for out-of-town tree enthusiasts was well established by 1913, when British urban planner and garden home advocate Ewart Culpin arrived on a speaking tour.

It included Mt. Hope Avenue, including both the cemetery and the Ellwanger and Barry nursery grounds; Highland Park, in particular its legendary arboretum; and the magnolias on Oxford Street and the stately elms on East Avenue.

Somehow, though, Culpin's tour must have gone off the script. In his speech to the Chamber of Commerce, the visitor complimented the city's horticultural fathers but also gently chastised them.

"Your beautiful streets are so beautiful that the contrast between them and your poorer streets is remarkable," Culpin said. "You have here parkways as beautiful as those in any other city in the United States ... But your aim shouldn't be primarily to make your city the most beautiful in the country, but to make it the best for all to live in."

The current inequality in tree cover in the city of Rochester is easy to observe, either through data or the naked eye. But that plain fact immediately raises a more difficult question: How did it come to be?

Broadly speaking, there seem to be two causes, one purely historical and one that continues to the present. The first ties back to the city's official moniker: the Flower City.

The nurserymen

For most of its early history, Rochester was known as an Erie Canal town. In the 20th century it would become synonymous with the Eastman Kodak Co. and other advanced manufacturers.

For several decades in the late 19th century, though, Rochester was known best as the Flower City, a title earned by a profusion of local plant nurseries, Ellwanger and Barry chief among them.

"The city of Rochester, beyond other cities, is dependent on its horticultural attractions for its superiority over other places," Horace Hooker, owner of a large nursery in southeast Rochester, said in 1879. "Deprive us of these, and we shall sink into the common level of mediocrity."

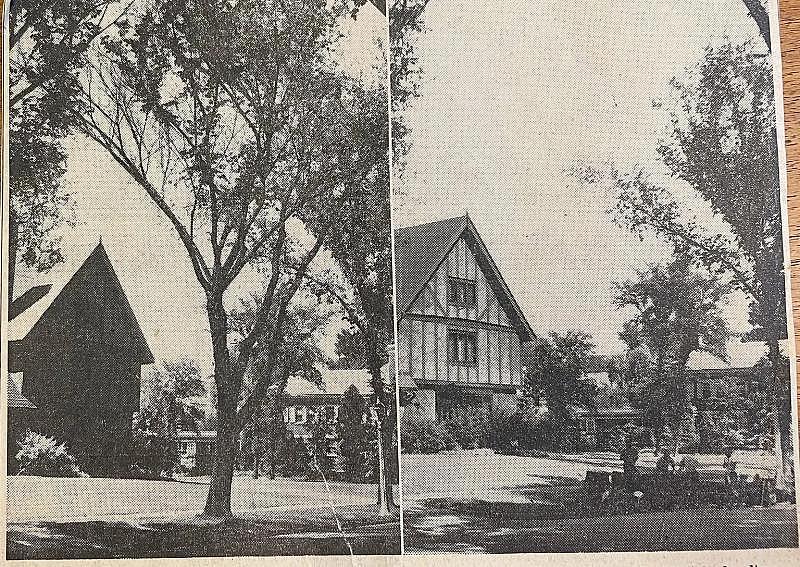

Trees along Douglas Road, with 111 Douglas Road on the left, near Park Avenue, in 1955 and 2021.

By the 1880s there were 35 nurseries in the Rochester area. Collectively they exerted massive influence on the national industry, supplying plants for parks and private developments across the United States.

The beginning of the end came in the last years of the 19th century, when a nationwide insect infestation wrecked their distribution network. Facing the demise of the industry as they knew it, Rochester's nurserymen pivoted to the real estate business in a way that shaped the physical future of the city.

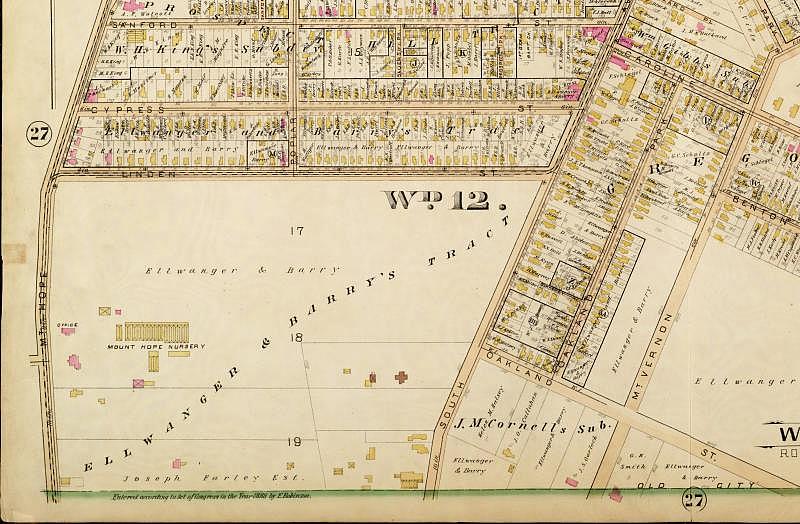

Ellwanger and Barry, for example, sprouted a development entity that soon exceeded the plant nursery in profitability. The current South Wedge and Highland Park neighborhoods stand largely on former nursery land, and the nurserymen used their reputations and horticultural acumen to establish the new developments as luxury living.

"They’re very consciously parsing out the former nursery grounds and making these very high-end homes that are beautifully planted with great boulevards for the wealthy elite in Rochester," said Camden Burd, a historian at Eastern Illinois University who wrote his doctoral dissertation at the University of Rochester on the nursery industry here.

AN 1888 PLAT MAP OF MOUNT HOPE AND SOUTH AVENUES. ROCHESTER PUBLIC LIBRARY LOCAL HISTORY & GENEALOGY DIVISION

Your beautiful streets are so beautiful that the contrast between them and your poorer streets is remarkable. You have here parkways as beautiful as those in any other city in the United States ... But your aim shouldn’t be primarily to make your city the most beautiful in the country, but to make it the best for all to live in. - Ewart Culpin, British urban planner in 1913

Horace Hooker laid out housing on part of his nursery and planted magnolia trees down a grassy center median, making Oxford Street one of the city's most memorable boulevards. Vick Park A and B, off Park Avenue, are on the site of James Vick's famous and influential seed garden. The Browncroft neighborhood was developed from the Brown Brothers Nursery. Across the Genesee River, the former Genesee Valley Nurseries begat Genesee Park Boulevard.

The nurserymen were well connected politically, including a dominant influence on the city Parks Commission. They sold their land off piecemeal while squeezing out additional profit from their remaining plantings in the meantime.

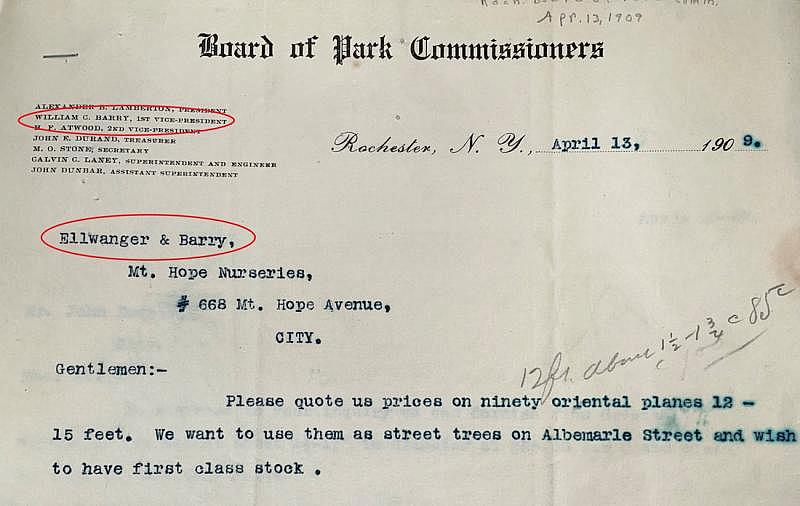

For example, William C. Barry, then president of Ellwanger and Barry, was also vice president of the Parks Commission and signed off on many large public purchases from his own nursery.

A 1909 purchase request from the City of Rochester Parks Commission to Ellwanger and Barry, demonstrating the conflict of interests inherent in the roles of men like William C. Barry. ELLWANGER AND BARRY PAPERS, RARE BOOKS, SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND PRESERVATION, UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER

There were nurseries northeast of downtown Rochester, too, if not quite as many. But for several reasons — the presence of extensive railroad tracks, for instance, as well as the placement of Kodak Park and the Rochester Public Market, both on former nursery grounds — they were not converted to such pastoral housing developments.

Instead, the northeast, broadly speaking, was the landing place for arriving immigrants from Italy, Germany, Poland and other European countries. After World War I, Black people from the South began moving there as well.

In contrast to other parts of the city, the northeast was developed in haphazard fashion, with little consideration for aesthetics or green space.

We have been so in the habit of thinking of the very beautiful part of what is, on the whole, a very beautiful, healthful, well-drained city, that all have lost sight of the fact that we have people with children living under conditions of which we have no reason to be proud. - George Goler, longtime public health director in 1901

"It was a port of entry for immigrants, a place built as a slum before anyone now alive can remember," a reporter wrote in 1973. "It was vibrant — a working-class district of ... narrow streets without trees."

George Goler, the influential longtime public health director, commented in 1901 on the same disparity that Ewart Culpin noticed 12 years later.

"We have been so in the habit of thinking of the very beautiful part of what is, on the whole, a very beautiful, healthful, well-drained city, that all have lost sight of the fact that we have people with children living under conditions of which we have no reason to be proud," he said.

That fundamental observation — the prosperity of some obscuring the poverty of many — has colored much of the city's history. The tree canopy serves simply as an unmistakable visual marker.

Citizen engagement

Certainly the plant nurseries and their well-connected owners exerted an influence on how Rochester grew at the time. But it has been more than 100 years since most of that land was developed. Why do the same patterns persist?

Perhaps the best place to look is Rochester's most famous tree-lined boulevard, East Avenue.

One clue comes from 1938, when the city's socialite class waged a pitched battle over a proposed widening of East Avenue — and, in particular, the tree removals it would require.

"The removal of any more trees would be a disgrace," said John McInerney, president of the Rochester Automobile Club. "It is a beautiful street, and the residents on it pay a high tax to live there. They certainly ought to be protected."

The city of Rochester, beyond other cities, is dependent on its horticultural attractions for its superiority over other places. Deprive us of these, and we shall sink into the common level of mediocrity. - Horace Hooker, owner of a large nursery in southeast Rochester in 1879

Fifty-one years later, Nan Johnson, a Monroe County legislator and public health advocate, made the same point during another reconstruction project.

"The mere mention that any of these trees would be removed is enough to elicit the legendary wrath of the citizens of the East Avenue area," she wrote. "As a matter of fact, it seems clear that the city has already backed off of any such proposal."

It takes some doing to get a street tree to thrive, not least of all regular trimming and general solicitude on the part of the municipality. Residents with the time, tools and inclination to lean on their local government are more likely to obtain the results they want, in trees or anything else.

Trees looking east down Rockingham Street in 1915 and 2021, with 153 Rockingham being the house at the far right.

That seems to be what has happened with the tree canopy in Rochester: the subtle gains from political pressure by wealthier, better organized neighborhoods have accumulated over the years into a stark and durable difference in tree cover.

The effect has been most apparent during times of major tree loss: as roads were being widened for automobiles in the 1930s; the height of Dutch elm disease in the 1960s; and the ice storm in 1991.

Tom Argust was the commission of parks, recreation and human services in 1991. He recalls the arduous work of clearing downed trees on streets and in parks after the weather event — and then the even more delicate job of deciding which additional trees should be cut down for safety's sake, and where others should be planted.

In that instance, politically savvy residents in the 19th Ward and Browncroft neighborhoods, among others, leaped into action, going so far as to hire their own arborist to rebut the city's conclusion that some of their trees needed to come down.

"Citizen engagement and participation and citizens doing their homework and knowing how to work the system – it gets results," Argust said. "A lot of these citizens in the 19th Ward, Browncroft, South Wedge – a good number of them really did their homework about trees. They were able to at least ask really good questions of the forester."

In the northeastern quadrant of the city, meanwhile, residents could do little but mourn the ash trees that the city removed.

"I'm going to have to get an awning or something now," one longtime homeowner said in May 1991. "In the afternoon, without these trees, it's just like a sunburst. You can't sit out in the living room, even with the air conditioning."

The same dynamic played out over decades starting in the late 1940s, when the first of a series of pests and pathogens began to wreak havoc on the city's trees. The most damaging was Dutch elm disease, which from 1950 to 1975 claimed nearly every elm tree in Rochester.

In 1959, the city experimented with planting supposedly blight-proof trees in a few test areas — all in the southeast quadrant near Highland Park and Mt. Hope Cemetery.

‘Who cut this down?’

Broadly speaking, the city forester's files in the Municipal Archives, as well as the newspapers' letters to the editor sections, are bristling with requests, recommendations and admonitions from residents in wealthier, mostly white neighborhoods. Other neighborhoods have not applied the same pressure and so over time have been left living on less green streets.

Nina Bassuk is program leader of the Urban Horticulture Institute at Cornell University and was involved in assessing Rochester's tree canopy after the ice storm, in particular in the parks.

"Some people will not be engaged, or will not ask to be engaged, in the process," she said. "As opposed to people who take it upon themselves to be spokesperson for the trees."

I’m going to have to get an awning or something now. In the afternoon, without these trees, it’s just like a sunburst. You can’t sit out in the living room, even with the air conditioning. - A homeowner in 1991 after an ice storm destroyed a number of trees

Today, the notes written by forestry technicians in the official city tree inventory reflects the same process. There are more handwritten notes for trees in the southeast quadrant than for trees in the rest of the city put together, with many acknowledging the weight of homeowner pressure.

"NEVER prune this tree without speaking to carol first!!!!" one note reads for a tree in the Park Avenue neighborhood.

In the northeast, meanwhile, most of the notes have to do with trees being removed or refused. One such note, for a disappeared hackberry tree in the Upper Falls neighborhood, serves to summarize the entire history of trees in the neighborhood: "Who cut this down??"

Contact staff writer Justin Murphy at jmurphy7@gannett.com.

This story was originally published by Democrat & Chronicle.]