How Florida left farmworkers out of its COVID-19 pandemic response

This story was produced by Janine Zeitlin, a participant in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2020 Data Fellowship.

Other stories include:

What is Florida’s plan for vaccinating thousands of farmworkers? It’s unclear

Nikki Fried to Gov. DeSantis: Give Florida farmworkers, all teachers COVID-19 vaccines now

Florida farmworkers struggled to get vaccinated. But health officials finding ways to help

We had to work twice as hard': How the pandemic magnified inequities for Florida's migrant students

Norma Caldon, left, and Inocente Ordoñez, right, wash their hands before getting on a bus to work in Immokalee on Friday, April 3, 2020. The hand washing station, supplied by Lipman Family Farms, is one of many that have been placed throughout the community.

Alex Driehaus/Naples Daily News/USA TODAY - FLORIDA NETWORK

The sting of the needle dulled the fear of death that compelled Armando Izaguirre to the strip mall vaccination clinic.

“I lost a nephew,” Izaguirre said, “and that’s really scary. ... When you lose somebody close to you, it’s like, uh oh, wake-up call.”

His nephew died of COVID-19 and worked in agriculture, as does Izaguirre.

Armando Izaguirre, of Immokalee, has a bandage applied to his arm after receiving his COVID-19 vaccine during a Healthcare Network vaccination clinic, Tuesday, Feb 9, 2021, in Immokalee. Jon Austria/Naples Daily News USA TODAY NETWORK - FLORIDA

A month earlier, the 68-year-old farmer had pulled into the same Winn-Dixie lot in Immokalee and, to his shock, found a mass of well-heeled coastal retirees on a vaccination pilgrimage to the small inland town.

But no spot for him. Immokalee is a hub for surrounding fields that produce America’s tomatoes and oranges and Izaguirre’s lifelong home.

“I’m looking at all these people that I’ve never seen in my life and all these expensive cars out there. Mercedes. I mean, Bentleys. Corvettes, brand-new Corvettes! And I’m like, man,” Izaguirre recalled. “$300,000 cars!”

The per capita income in Immokalee is $12,000. Izaguirre drives a truck.

The pandemic ignited high infection rates and deaths in this farmworker community last spring and summer.

“This town got slammed,” said Joseph Brister, director of Immokalee’s sole funeral home, noting most of the COVID-19 deaths were older men with pre-existing conditions who worked in agriculture.

“I had four really bad months here. … I didn’t get much sleep.”

The death toll and the state’s inadequate and lagging response to the health needs of farmworkers throughout the pandemic reflect a public health failure that devalued the contributions of workers who were deemed essential, farmworker advocates say.

And that neglect has implications reaching beyond the Sunshine State, advocates say.

“It’s urgent that agricultural workers are vaccinated before they travel to other states,” said Lupe Gonzalo of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers. “More than anything, there’s a lack of responsibility, and again we’re seeing the same thing: another rather large failure in bringing necessary resources, urgent resources to farmworkers.”

The coalition estimates about 20,000 migrants live in Immokalee during harvest season.

Gov. Ron DeSantis announced last week that the state will open vaccines to anyone 18 and older on April 5, leaving co-health care providers and nonprofits scrambling to reach thousands of migrant workers who start heading north in April.

Workers and towns people wait in line to be tested as a farm bus delivers more workers from the fields. Busses drop off migrant farmworkers in the center of town, near CIW and Mission Peniel, in Immokalee. COVID-19 Rapid tests, education and results are provided by a Healthcare Network, CIW, working together with PIH to address the unique needs of this heavily immigrant community. Andrea Melendez/The News-Press/USA Today, Florida Network

Gonzalo welcomed the governor’s “long overdue decision” but called for streamlining the registration process so farmworkers can be vaccinated before harvest season ends.

“The vaccine rollout thus far has been challenging for low-income people without the time or technology required to get appointments. We fear that leaving the onerous registration process unchanged, Florida will continue to endanger its essential workers and hamper its own efforts to control the spread of the virus.”

Nikki Fried: Farmworkers have not been on governor’s radar

In early March, DeSantis said he was done vaccinating by job, making it clear farmworkers would not be prioritized, despite a federal recommendation to give them early access, despite pleas from growers and advocates, and despite health, living and working conditions that make them more vulnerable.

A University of California, San Francisco study found that Latino food and agriculture workers were in the most at-risk category for death during the pandemic.

“Making sure that their health was a top priority, that just has not been on the governor’s radar,” Florida Agriculture Commissioner Nikki Fried said. “Not only because the fact that he didn’t help when we had asked for help to make sure there were testing sites, the PPE, and the educational opportunities for our farmworkers, but then blamed them for outbreaks.”

The governor attributed the summer surge in cases to “overwhelmingly Hispanic” farmworkers and day laborers and noted that “the No. 1 outbreak we’ve seen is in agricultural communities,” according to reporting at the time, though he later clarified he didn’t mean to blame workers. Urban pockets of poverty, mostly in the Miami area, have counted the highest per capita rates, according to data from earlier this year.

Fried, when asked, graded DeSantis’ work in serving farmworkers an “F.”

Her office partnered with the Florida Division of Emergency Management, the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences and local governments to host farmworker testing events and worked with the institute to launch bilingual vaccine education and create farmworker safety videos.

Fried was unaware of state dollars specifically targeted for farmworkers during the pandemic.

“Outside of what minimal amount we’ve spent on creating those videos ... I don’t think there was any other money that we may have spent, and certainly I do not know of any other state resources that would have been spent.”

She praised the $6 billion in expanded pandemic assistance to farmers the U.S. Department of Agriculture announced last week that will also provide for PPE and protection for farmworkers.

Edwin Canas administerss a COVID test to a farmworker. Busses drop off migrant farmworkers in the center of town, near CIW and Mission Peniel, in Immokalee. COVID-19 Rapid tests, education and results are provided by a Healthcare Network, CIW, working together with PIH to address the unique needs of this heavily immigrant community. Andrea Melendez/The News-Press/USA Today, Florida Network

Lack of transparency, and was there a plan?

State agencies have not been transparent about how farmworkers factored into Florida’s COVID-19 response. The governor’s office, the Department of Health and the Division of Emergency Management have not fulfilled records requests sent in February asking for state plans, coordination efforts and how much the state spent on reaching farmworker and rural populations during the pandemic.

Nor did they answer if a plan to serve farmworkers existed.

Florida gave first vaccine priority to residents 65 and older before opening it to those 50 and older and then 40 and older. Many of the state’s farmworkers, who number between 100,000 and 200,000, don’t fall in those age groups. But even the young are vulnerable.

Researchers estimated that 75% of Florida crop workers have at least one underlying health condition that puts them at risk of developing COVID-19 complications.

“A common perception is that a typical crop worker should be in a good state of fitness due to the physical demands of their farm jobs. However, this perception does not appear to hold," according to an article in Choices, a publication of the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association.

An estimated 19,000 Florida agriculture workers have tested positive for COVID-19, according to Purdue University’s Food and Agriculture Vulnerability Index. At least 9,000 workers across the country have died from it, a researcher estimated.

The governor’s age restrictions have pained providers well aware of the high risks for farmworkers and with missions to serve the most vulnerable. Healthcare Network, a federally qualified health center, had been unable to distribute vaccines to anyone under 50 per state guidelines.

“We will target those folks so we can offer them these vaccines, but the vast majority are younger than that,” said Dr. Emily Ptaszek, CEO of Immokalee-based Healthcare Network, before the state announced dropping the age limits. “It’s extremely frustrating. Frustrating is not even an appropriate word. It feels terrible for a team of community health advocates to not be able to take care of people the way we know we can.”

The median age in Immokalee is 29.

Of the 3,000 residents the network has vaccinated in Immokalee and two other communities, only about 20 have been farmworkers, a count Ptaszek called “dreadfully low.”

Also worrisome is the clock. “There is a pressing need to inoculate our already hard-to-reach migrant farmworkers,” she said. “The state’s expanded eligibility will provide us latitude to reach this unique group.”

Workers start migrating in April and are gone by June, she added. “Then another community has to deal with this issue.”

Sindia Vasquez, 13, Juana Lopez and Flor Perez, 14, all of Lake Worth attend the Public Prayer to Honor Farmworkers Lost Due to COVID-19 event at the Saturday March 27, 2021 at the Palm Beach County Health Department in West Palm Beach. Meghan McCarthy, MEGHAN McCARTHY/Palm Beach Daily News

Rural Florida towns hit hard by COVID-19

Several Florida towns with farmworker populations have been disproportionately impacted with infection rates higher than the state average and up to three times more than nearby wealthier communities of retirees, according to a March analysis of state data.

As of March, Immokalee still counted the highest number of cases in Collier County, with an infection rate double the rate of Pelican Bay, home to wealthy retirees and Collier’s first private residential vaccine clinic.

In Palm Beach County, rural South Bay had an infection rate three times that of seaside Jupiter. South Bay was among the predominantly Black farming communities where leaders criticized the governor for leaving out low-income residents who did not have cars to drive to distant Publix stores, which have served as state vaccination hubs. The governor then opened a drive-thru site.

Other communities with farmworker populations in Palm Beach, Indian River, Martin, Hendry, Glades and Manatee counties also had higher infection rates.

“The pandemic has really turned the world upside down. Then again, the people at the bottom are the ones who feel it the hardest. In this case, it has been the farmworkers,” said Lourdes Villanueva, director of farmworker advocacy at Redlands Christian Migrant Association, which runs child care centers across the state. “These are families that live in our communities; their kids go to the schools. It really behooves us to make sure we include them.”

Response reflects farmworkers are essential but ‘disposable,’ advocates say

The inaction around vaccines has felt like another rebuff for farmworker advocates, who have spent the pandemic collaborating on how to reach farmworkers with accessible testing and trusted providers when their health care needs went unacknowledged in the state response.

“The most difficult part is to be called essential and at the same time experience that you are disposable,” said Pastor Miguel Estrada of Immokalee’s Misión Peniel, one of the nonprofits that banded together during the pandemic to reach underserved Immokalee residents. “When basically the government doesn’t provide for you the minimum stuff to show you that you are important to them, I think that’s exactly what they mean.”

On a Friday evening, farmworkers in boots and masks streamed off school buses that carried them from the fields into a parking lot near Misión Peniel, which gave them food. A mother in her 30s was among them.

It was her second week back picking tomatoes after months of being unable to work to care for her family.

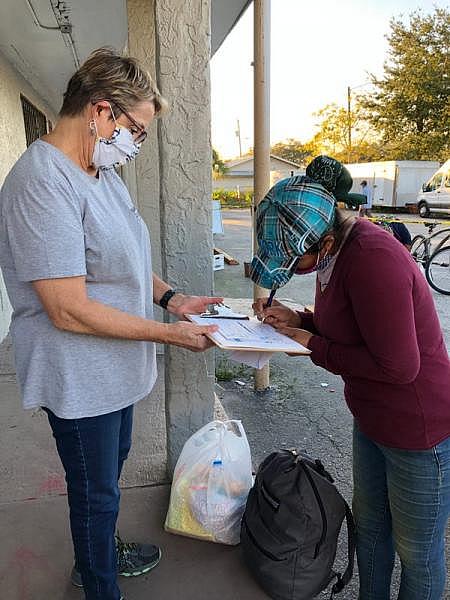

Ruth DeYoe of Mision Peniel in Immokalee requests the signature of a farmworker who is receiving financial help from the social services organizatioon in January 2021 after the woman's son tested positive for the coronavirus and she was unable to work. Janine Zeitlin/USA Today Network Florida

The mission offered her help with bills. She hoped she’d receive the vaccine soon.

“If they’ll give it, I’ll take it,” Juliana said in Spanish. She migrated from the Guatemalan highlands to escape poverty. “Because I have experience with this illness. And it’s very difficult to get out ahead of it.”

The USA TODAY Network - Florida is not fully identifying Juliana because she is undocumented and fearful of how deportation would impact her children.

Palm Beach County’s Guatemalan Maya Center hosted Saturday evening testing for several months targeted for when farmworkers would not be working. Those events counted a 30% infection rate, said Lindsay McElroy, a spokeswoman for the center, an organizer of a public prayer on March 27 to honor farmworkers lost because of COVID-19.

The center produced messages and videos in indigenous Mayan languages and worked with the state health department in Palm Beach County to find solutions for the state’s ID requirements for vaccines that are difficult for farmworkers, particularly the undocumented, to meet. She noted officials will allow the center to write a letter establishing proof of county residency.

The governor has not responded to the center’s appeals for greater health care access and vaccines, McElroy said. “His actions have been explicitly discriminatory toward our community.”

Nor did he respond to a letter from Palm Beach County Commissioner Melissa McKinlay, the commissioner said.

“I am disappointed there is such a failure in state leadership to recognize the immense importance our farmworkers play in public safety,” she told The Palm Beach Post.

Stronger state coordination around farmworker issues is long overdue, advocates say.

“I keep saying we should re-establish the advisory council,” said Arturo Lopez, executive director of the Coalition of Florida Farmworker Organizations, who was on the governor’s farmworkers advisory council in the late 1980s. It was dissolved in the early ’90s and he has since appealed to the state to revive it.

So far, unsuccessfully.

Growers, UF, Fair Food Program provide farmworker protections

Florida’s $147 billion agriculture industry is the state’s second-largest industry after tourism, according to state officials. Growers had also petitioned the governor for vaccine priority for workers citing their “vital” role in providing a “safe and abundant food supply.”

“Florida is the ‘winter breadbasket’ for the entire country,” Aaron Troyer, chair of the Florida Fruit & Vegetable Association, wrote to DeSantis in December. “The health and well-being of the agriculture workforce is the top priority for Florida growers, who have taken extraordinary measures, completed extensive training and made substantial investments in workforce protection against COVID-19.”

About 800 farm labor supervisors participated in COVID-19 training on protecting workers, said Gene McAvoy, an associate director at UF’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences center in Immokalee.

The program relied on federal Centers for Disease Control guidance on how to protect agricultural workers against COVID-19. There are no state mandates on protecting farmworkers from the virus, according to Fried and other experts.

A bus picks up dozens of farmworkers outside of La Fiesta #3 in Immokalee on Friday, April 3, 2020. Alex Driehaus/Naples Daily News/USA TODAY - FLORIDA NETWORK

“Many companies have mandates. … some are more than stringent than others,” McAvoy said. “In the fruit and vegetable business, you can’t afford to have a bunch of people out sick.”

The Coalition of Immokalee Workers’ Fair Food Program developed “the first privately enforceable” COVID-19 protections for farmworkers in the United States, said Laura Safer Espinoza, a retired judge and executive director of the council that oversees the program. “That’s critically important in states that have not passed mandatory legislation or pledged resources for enforcement.”

The program counts many large growers, which represent 90% of Florida tomato production as well as the largest cut flower producer on the East Coast, and operates in seven states including Florida.

Consumers “have to worry about” farmworkers, said Luis Peña-Lévano, an assistant professor of agribusiness and resource economics at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore. “Because they are labor, they represent one of the key factors” of successful production.

Increased costs of labor and measures to protect workers can trickle down to the buyer, he said, and higher food prices might be yet to come. “It will take some time to see.”

Pandemic shows need for local health control

Mary Montes fanned her frail 90-year-old mother, who sat atop her walker as they waited for her vaccination under a bright winter sun.

Agnes Barrera grimaced and curled her hand into her frail body. Barrera suffers from arthritis after a lifetime of picking crops, explained Montes, her mother’s caregiver.

Like many farmworkers, Barrera’s first language is not English but an indigenous language. In her case, she speaks the language of the Shuswap tribe of Canada. Like most farmworkers, she was initially shut out of the vaccine.

But after the first Immokalee state-run vaccine event, which required online booking and drew seniors from hours away, Healthcare Network offered to take the lead and worked with the Coalition of Immokalee Workers and Partners In Health to provide intensive, even door-to-door outreach. The Florida Department of Health provided space and support.

Agnes Barrera, of Immokalee receives her COVID-19 vaccine by Healthcare Network Dr. Douglas Halbert Tuesday Feb. 9, 2021, in Immokalee. Jon Austria /Naples Daily News USA TODAY NETWORK - FLORIDA

Montes warned the doctor inside giving her mother a shot: “She’s going to kick.”

Barrera stomped as forewarned.

“All done!” Montes assured her mother. “No coronavirus is going to get us.”

The same cannot be said of the current workforce.

Ptaszek would like to see the state health department allow its local leaders, which the network has been coordinating with, greater leeway to meet community needs.

“It’s hard to be talking about equity and distribution,” Ptaszek said, “and then not quite have the support and the pathway to do that.”

“Health care is really local.”

Janine Zeitlin is an enterprise reporter in Southwest Florida. Consider supporting local journalism by subscribing. Connect with her on Twitter @JanineZeitlin or at jzeitlin@gannett.com.

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 Data Fellowship.

[This article was originally published by Naples Daily News.]