How Minnesota’s Foster Care System Reminds Native Moms of a Racist Legacy

This project was produced as a project for the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2021 National Fellowship.

Other stories by Jessica Washington include:

Mother Jones illustration

Ricky Turner/Unsplash

Teresa Nord prefers the peacefulness of her new rural home hours outside of Minneapolis, but today she’s seated in a retro diner outfitted with plush booths and vintage tables, one of her favorite places in the city.

She quickly decides on a BLT salad with chicken and wild rice soup, then engages in a remarkably easy conversation, floating between her own story and those of Native women and families she’s helped as a parent mentor over the last few years. But tears begin to fill her deep blue-green eyes when she talks about her own daughter – and how she nearly lost her.

Since 2018, Nord has worked at the Indian Child Welfare Act Law Center, an organization dedicated to helping Native mothers and families reunite with their children in the foster care system. She sees the legacy of generations wrapped up in the child welfare system. She can tell you which judges allow smudging, a traditional practice for many tribes that helps alleviate stress and anxiety, before court. And which social workers are particularly “nasty” to Native moms.

“For the families that we work with, it’s constantly living in a state of fear,” says Nord. “Grandma was in the system and now Mom is in the system and now the child is in the system… How can we expect our community members to even start healing?”

Nord, who is a Navajo and Hopi Indian descendant, has experienced that fear herself. In February of 2015, Nord temporarily lost custody of her 6-year-old daughter after a social worker determined she “was in imminent danger.” It took two years to get her back.

“Grandma was in the system and now Mom is in the system and now the child is in the system… How can we expect our community members to even start healing?”“I live with this constant fear,” says Nord. “I call it child protection PTSD, that they’re just gonna one day knock on my door.”

Native children like Nord’s daughter are significantly overrepresented in the child welfare system. Minnesota’s history of separating Native children from their families through so-called “boarding schools” and mass adoptions weighs heavily in the minds of Native moms today, many of whom feel that history is repeating itself within today’s child welfare system.

No two stories of parents involved in the child protective system are the same, but Nord feels she’s seen enough as a Native mom and working with other women to notice a pattern: Too often social workers default to removing Native children—and those presumed to be Native—from families experiencing difficulties.

“There is such a long history of removal just because of the texture of [the mother’s] hair or the color of their skin,” says Nord. “[Families] are never really given a chance.”

For the last eight months, The Fuller Project has investigated the child welfare system in Minnesota.

From the testimony of more than 20 people involved in the child welfare system in Minnesota—including mothers like Nord, lawyers, historians, politicians, bureaucrats, judges, and activists—it’s clear that for many Native mothers, the fear of having their children ripped away from them and the ripple effects of generations of Native removals remain omnipresent.

In Minnesota and across the country, many non-Natives have just begun to reckon with the atrocities of boarding schools where state and federal officials sent Native children who were removed from their homes to “re-educate” them.

While the specific horrors of that time are over, the trauma and continued impact for those who experienced it and for their descendants is very much alive in Minnesota, says Holly Henning, deputy associate director at Ain Dah Yung Center, a Native-run Twin Cities emergency shelter for youth, many of whom are involved in foster care.

“I feel like child protection is a continuation of the oppressive [boarding school] systems,” says Henning. “I have family that are boarding school survivors, and the stories they’ve told…I see that play out with child protective services.”

Nord, who also has family members who were boarding school survivors, says that, like many Native moms, her first interaction with CPS was before she was a parent.

Throughout her childhood in Minnesota and California, Nord remembers CPS workers repeatedly visiting her mother, who was blind. Her mother’s disability made many people doubt her ability to parent, Nord says.

“It felt like this looming cloud over us,” Nord recalls.

In her teens, Nord struggled with substance abuse, but says she was sober by the time she gave birth to her first child in 2008.

After suffering a back injury while playing volleyball, Nord was prescribed opioids by her doctor, which she says kickstarted a relapse.

“I was living a sober, stable life. I was working hard as a single mom,” she says. “Within a very short period of time as a result of my relapse, which was a result of being injured and handed handfuls of medication from doctors… my life just spiraled out of control.”

Things escalated quickly. In September of 2014, she was arrested for second-degree possession of heroin. The drug charge, and her daughter’s absence from school while Nord was in jail, landed Nord on the school’s radar.

But it was Nord’s plea for help, she says, that led to her daughter’s removal from their home.

In February 2015, Nord’s daughter, then 6, confided that a family friend had abused her. Devastated, Nord, who was under investigation by CPS, says she immediately reached out to a social worker urgently seeking support for her daughter.

Instead, her daughter was immediately removed from her care. Nord was charged with neglect, and her daughter was placed in foster care.

“The foster provider told her that your mom is a bad mom, you’re never going to see her again, [and] you might as well get used to that,” says Nord.

After serving less than a year in prison for her drug charge, she regained custody of her daughter, who is now 13; she also has a 3-year-old, born after her recovery.

But the scars of foster care and her battles with CPS still haunt Nord and her teen daughter.

“When [parents] do get their kids back, the initial thought is, it’s going to be rainbows and butterflies, but it’s not,” says Nord.

Nord says her daughter struggles with multiple mental health and behavior disorders, which Nord says were exacerbated by her removal. Though the girl’s welfare is her priority, the trauma of her previous case can make asking for help difficult.

“I always have that fear, like if I reach out for help, are they going to misconstrue this as something it’s not based on the fact that I had an open child protection case, and I lost custody of her at one time,” she says. “That fear is always there. It’s not something I can shake.”

Teresa Nord poses for a photo, on Oct. 12, 2021 at the ICWA Law Center, where she works as a parent mentor. Nord, who is a Navajo and Hopi Indian descendant, says she had her daughter removed by child protective services. Jessica Washington/The Fuller Project

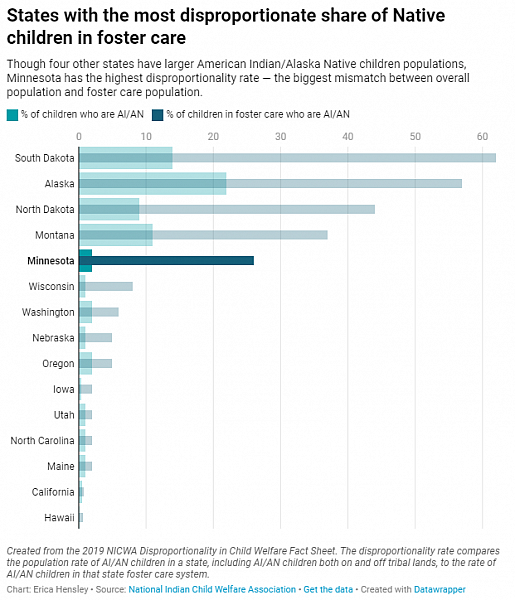

In 2014, a year before Nord’s daughter was placed in foster care, only 1.4% of children in Minnesota were identified as American Indian, but nearly one in four children in the Minnesota foster system were listed as American Indian, according to a 2017 report by the National Indian Child Welfare Association (NICWA).

Though advocates argue that policies have improved on the margins over the last few years, the numbers continue to show stark differences between white and Native families in Minnesota’s child welfare system.

In December, NICWA released a new report showing that in 2019, roughly 26% of children in Minnesota foster care identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native. That same year, only 1.7% of children in the state identified as AI or AN. The report found that Native children were overrepresented in the foster care system at 15 times the rate of their non-Native peers.

According to NICWA, disparities between Native and non-Native children are likely even higher because, it has found, Native children are routinely undercounted in the child welfare system.

Overall, Native children in 2019 were 16.8 times more likely than white children to be in out-of-home care, according to an October 2020 Minnesota Department of Human Services report. This number does not include children in the state who identified as two or more races, over half of whom had American Indian as one of those races. Children of two or more races saw the biggest jump in out-of-home placements in 2019.

Even in urban areas like Minneapolis, where the county board declared racism “a public health crisis,” the disparities between Native families and white families in the child protective system are still incredibly high, acknowledges Lisa Bayley, senior policy advisor on child wellbeing for Hennepin County.

Similar to the rest of the state, Native Americans make up roughly 1% of the population in Hennepin County, including Minneapolis, according to 2019 U.S. Census estimates. Yet Native children account for roughly 18% of youth in foster care and 13% of youth in out-of-home placements in Hennepin County.

“What we have now is not acceptable,” says Bayley. “It’s not acceptable at all, so we have to work towards changing them.”

In rural counties closer to tribal lands, like Beltrami County, the treatment of Native people in the child protective system is often worse, says Sadie Hart, an ICWA compliance court monitor in Minnesota.

Roughly 20% of the county identifies as American Indian alone. But about 88% of children in out-of-home placement in Beltrami identify as American Indian alone, according to a 2020 Minnesota Department of Human Services report. Beltrami County has not responded to requests for comment.

“When we look at the practices of our counties, our state, our federal government and their attitudes towards Native Americans, they are a problem,” says State Senator Mary Kunesh, a Standing Rock Sioux Tribe descendant, who represents Ramsey, Hennepin, and Anoka counties. “They’ve been a problem for so long, and we have to fix them.”

The story of how Minnesota began separating Native children from their families at such high rates predates the modern child welfare system, says Nicole MartinRogers, a White Earth Ojibwe descendant and senior research manager at Wilder Research, a research organization that works with nonprofits and governments.

“There’s a really explicit connection in the Indigenous community's mind between boarding schools and the child welfare system,” says MartinRogers. “Because [boarding schools are] how the system first started taking kids away from their families.”

In 1871, the first boarding school for Native children in Minnesota, the White Earth Indian School, began taking “students” from the neighboring tribes. The guiding philosophy of these boarding schools at the time can be summed up as “Kill the Indian, save the child,” an adaptation of the motto of forcible assimilation.

By the early 1900s, there were 16 boarding schools operating in Minnesota, pulling children from all 11 tribes within the state, according to the Minnesota Post.

Although the boarding schools, run primarily by Catholic nuns, called these children “students,” the majority were forcibly removed from their families, starved, and beaten. They were also forced to sever all connections to their Indigenous roots.

There aren’t records of how many Native children were removed from their families over the years in the United States, but according to the National Native American Boarding Schools Coalition, by 1926 nearly 83% were in boarding schools, which went on to operate into the 1970s.

For Valencia Little Thunder, 42, a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, the boarding school era is far more than a history lesson.

She remembers little of her early childhood, marked as it was by the turmoil of her mother’s substance abuse. Little Thunder spent her early years in the foster care system in Rosebud, South Dakota, before moving to Minneapolis with her mother at around age 9. When she was 11, Little Thunder remembers, her mom introduced her to alcohol and marijuana and would routinely get drunk and high with her.

Decades later, after becoming a mother herself and entering recovery, Little Thunder says she finally understood the underpinnings of her mother’s substance use. “She was a part of the boarding schools,” says Little Thunder.

Although her mother rarely talked about what happened to her as a child, Little Thunder says she was able to piece the story together by talking to her aunts and reading up on history.

“I see the impact,” says Little Thunder. “The using, the drugs, because [she was] abused… I accepted who she was because she’s been through a lot.”

Reclaiming her history has been a painful process, but one that she says made her fight even harder to reunite with her children and give them family and culture. Through the help of the ICWA Law Center, Little Thunder was able to win back custody of her two middle children, whom she’d lost custody of while in rehab.

She also went back to school and discovered she had a knack for it, graduating in 2009 from an adult high school diploma program.

“I really [did] everything that the white society said I couldn’t do,” says Little Thunder.

One of the things she’s proudest of is giving her youngest daughter the gift of their native language, which was taken from her mother. “She speaks fluent Dakota,” says Little Thunder proudly. “I feel a part of the solution.”

Valencia Little Thunder pictured here at Five Watt Coffee in Minneapolis, Minnesota on Oct. 11, 2021, is a member of the Lakota tribe. Her mother was a boarding school survivor, and Valencia had to fight to regain custody of her children who were placed in foster care. Jessica Washington/The Fuller Project

Mass removal of Native children from their homes didn’t end with the closure of the boarding schools, says historian Margaret D. Jacobs.

In her book, A Generation Removed: The Fostering and Adoption of Indigenous Children in the Postwar World, one of the premier texts on the so-called adoption era, Jacobs highlights the practice of mass adoptions and removals of Native children in the United States and other western nations following World War II.

“There was always a kind of eliminatory impulse going on in American society to eradicate American Indians,” says Jacobs, a professor at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln specializing in the American West, particularly Indigenous child removal. After the failure of the boarding schools to fully “assimilate” Native children, she tells The Fuller Project, “[white settlers] start thinking about adoption as a more effective way to carry this out.”

The boarding schools officially closed in the U.S. in the early 1970s. By 1976, roughly 13% of Native children in the state of Minnesota had been adopted, by overwhelmingly non-Native families, according to Jacobs’ research. Another 5.8% had been put into the foster care system. Native children in the 1970s were placed in foster care at 16.5 times the rate of non-Native youth in Minnesota, according to Jacobs. As of 2019, Native children in Minnesota are 16.8 times more likely to end up in out-of-home care than their white peers.

Much like the boarding schools, the adoption of Native children is largely viewed by the white-dominated system as being for the children’s benefit. But experts in Native history and culture, and many in the system themselves, say placement is often driven by factors like discrimination and cultural ignorance and causes individual and generational trauma, especially in families with a history in boarding schools.

“There’s a narrative in the United States about how adoption is this wonderful thing, and we always frame it as we’re giving children opportunities,” says Jacobs. “Coupled with this narrative we have about…dysfunctional Native communities, these two narratives came together in a very powerful way.”

In response to outcry from Native activists over the removals, Congress passed the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978, a law that adds special protections against removals for tribal citizens. In 1985, Minnesota enacted its own version, the Minnesota Indian Family Preservation Act.

These laws require the child protective system to work collaboratively with tribes, create longer timelines for parents to regain custody, establish higher burdens for removals and terminations of parental rights, and require that CPS engage in “active efforts” to keep Native families together.

But they protect only children who are enrolled in their tribes, explains Shannon Smith, executive director of the ICWA Law Center. Not all children of Native descent are officially enrolled in their tribes due to specific membership rules, including documentation and residency requirements. This means many Native-identifying children don’t have ICWA’s legal protections. “It’s based on a political relationship between a child and their tribe,” says Smith.

On top of that, the laws are under attack: Brackeen v. Haaland, a case winding its way to the Supreme Court, challenges the constitutionality of ICWA. Decades after these laws went into effect, family separation remains “intractable” in Minnesota, says Jacobs.

“There’s such a weird disconnect in Minnesota between this progressive rhetoric and this really racist structural system,” says Jacobs. “We’ve seen that with police brutality in Minnesota, but it’s also true in the child welfare system.”

The current system is just a variation on the same practices from decades ago, says Karl Nastrom, an attorney and Casey Family Program fellow researching the child welfare system in Hennepin County. “The boarding schools, the first people put on reservations…and then the adoption era. And then now, it’s the foster era,” he says.

Looking back on the boarding school and adoption era, it’s easy to say the philosophies underpinning those removals were wrong, says Smith, the law center director. “We realize to a certain extent that’s really absurd.”

But the underlying mentality persists, she says, as does the impact.

“We haven’t ever gotten to a point of the system being culturally humble or being like, wait a minute, we don't know better,” Smith says. “I think a lot of times removals [are] society… equating removal with safety. And that is an equation that is just automatic. And I think that’s fundamentally flawed.”

Henning, who runs programming at the Ain Dah Yung Center, says that “more often than not” she sees children removed from their families only to have something worse happen to them in out-of-home placements.

“They had lice for four months, so they were removed from the home. Then when they’re in out-of-home placement, they’re sexually abused, they’re physically abused. Their experiences of trauma and what they’ve had to go through has gone, like, times ten versus the original report,” Henning says.

Shana King, pictured here at her home outside of Minneapolis, Minnesota on. Oct. 10, 2021, is a Native mother who had her children removed. She is a member of the MHA Nation. Her late son is in the background. Jessica Washington/The Fuller Project

In 2009, Shana King, an enrolled member of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation who lives outside of Minneapolis, lost custody of two of her children while in the deepest part of her three-year addiction battle.

During her childhood, King says, she was repeatedly sexually and physically abused. Like Little Thunder, she ended up in the foster care system after making a report of physical abuse.

Throughout her adulthood, King dealt with periods of homelessness and eventually developed a short-lived but “severe” addiction to heroin, as she tells it. In September of 2009, she overdosed in a public park, leading CPS to remove two of her five children, who were 14 and 7 at the time.

From that moment on, King, who is Native and Black, says she felt demonized by her white social worker.

“I was a Native American mom who passed out with her white-looking son,” King says. “I wasn’t considered somebody who loved them… I was looked at as an addict who had two kids.”

Two years later, with the support of her tribe, King won back custody of her children. However, the impact of the foster care system on her children, especially on her youngest, diagnosed with severe cerebral palsy, lasted.

“When he went into foster care, they put him on like 33 different medications that I’m still winding him off from because he’s so addicted,” explains King. “It’s affecting his liver and kidneys.” Her son died in December at age 19.

Foster placement also denied her children a loving environment, King says.

“When I would go visit him, they said don’t hold him too much, he’s going to get used to that. Anytime he cried, they’d give him Valium,” she says. “They would tell my daughter, you can live with this foster family all the time because your mom’s never gonna not be homeless, and she’s always going to be poor.”

Working with her tribe, she was able to find housing and a treatment approach that was culturally appropriate. Looking back on how she and her son were treated, it’s hard for her to think removal was the right step.

“I never think that addiction is a reason to remove children,” says King, especially when removal is so culturally insensitive and further traumatizing in foster situations. “I really feel like we need to have spaces in our communities where we can have family treatment centers, where we can still eat dinner together and get the support we need.”

In Minnesota, and specifically in Hennepin County, where King currently lives, “drug abuse” and “alleged neglect” were the primary reasons for having a child removed in 2019.

But experts like Shannon Smith, who has worked in the child welfare space for over 20 years, say that when you dig deeper, poverty—which Native women disproportionately experience in Minnesota—is often at the root cause of these removals.

“If we were to take a society as a whole and start removing kids for every person who was struggling with maybe abuse of alcohol, our system would be overwhelmed,” says Smith. “But when you’re poor and you're using, all of a sudden it becomes…the reason to take the kids away.”

Indeed, some experts say, poverty can often look like neglect to social services workers, especially in families of color. Even when poverty is causing instability that puts kids at risk, removal may not be the best option and can exacerbate rather than fix the root issues.

In Hennepin County, where the ICWA Law Center is located, Native Americans account for roughly 26% of those living in poverty, although they make up just 1% of the population, according to the county’s 2018 report Child Protective Services: Reform and Child Well-being.

“There are so many Indigenous families living in poverty, it’s hard not to consider it neglect… if the caseworker walks into the house and there’s no food in the refrigerator or the kids don’t have a bed to sleep on or other things that can result from someone just being really poor,” says Nicole MartinRogers of Wilder Research.

The impact of boarding schools and generational trauma also can’t be separated from the current child welfare issues in the state, says MartinRogers, whose grandfather is an Ojibwe boarding school survivor.

It’s a “vicious cycle,” she says, because each generation loses that connection to their family and culture. “All that generational trauma, it feeds into the disproportionate number of Indigenous families that are involved in the child welfare system,” she says.

Lack of Native representation in the child welfare system in Minnesota also drives these disparities, MartinRogers says. Roughly 92% of social workers in the state are white, according to Minnesota’s 2020 Social Worker Workforce Report; statistically zero percent identify as American Indian.

“If we have all white women who come from middle-class backgrounds who are making the determination about when someone is abusing or neglecting their child, that's a problem,” MartinRogers says.

As a result, rather than honor cultural differences in parenting practices or treat the underlying issues of poverty, disinvestment and trauma, CPS often decides to treat the symptom, says Mary Kunesh, the state senator.

“They think the very best thing is to remove the kids from their families when actually, the best thing that we can do is remove the issues and the barriers that are causing that family to struggle,” she says.

Bridget Sabo, an attorney and parent advocate in Hennepin County, says that in child protection cases, legal standards can get “mushy,” unlike in criminal cases, which often revolve around concrete evidence. “Whenever we're talking about kids, we're talking about parenting, we're talking about culture,” Sabo says. “That's a completely subjective standard. When you come into someone's house, is this house safe? Are these practices safe?”

In urban areas, most referrals of Native moms to CPS come from schools, but in the suburbs, most reports tend to come from the criminal justice system, which also disproportionately impacts Native women, says Hart.

Native women are sentenced to prison at a higher rate than all other races, according to the 2020 Status of Women in Minnesota report, which found that 14.7% of Native American women in the state have been sentenced to prison compared to 11.5% for women of all other races.

Data collected by the report from the Minneapolis Police Department from 2016 to 2018 show that Native women are significantly more likely to be stopped and searched than women in other racial groups. Native women made up only 2% of all traffic violation stops of women during that time period, but they accounted for 24% of all women stopped for being a “suspicious person.”

For Native youth, particularly girls, the disparities in the justice system both mirror and influence their experiences with child protective services. Roughly 50% of Native girls in 9th and 11th grades in Minnesota have had a parent in jail or prison at some point, the highest proportion of any group.

“I look at my story and look at the multiple systems that were in play…the criminal justice system, the child protective system, there were all of these different components. And nobody was communicating, nobody was saying, ‘Hey, what resources or prevention or wrap-around services can we push?’ ” says Teresa Nord, who nearly had her parental rights permanently terminated while in prison.

In order to address the disparities in the child welfare system, the law center’s Smith says the approach should be holistic. “When we start talking about the world of child protection, it forces us to bring in all issues and disparities that are prevalent throughout all systems,” Smith says. “When we think about criminal justice, when we think about issues of chemical health and mental health, when we think about economic disparities, all of those kinds of come together in the world of child protection.”

In roughly 20 years working in social services in Minnesota, Tikki Brown has started to see real efforts at changing the system in the last 10. “We do have a number of efforts,” says Brown, assistant commissioner for Children and Family Services for the Minnesota Department of Human Services. These include partnerships with Minnesota’s tribes and cultural sensitivity training for staff, which she says have led to “slight” improvements.

In Hennepin County, Justice Anne McKeig, the first Native American to sit on any state Supreme Court and a former child and family services prosecutor in Hennepin County, oversaw several reforms aimed at improving the disparities for Native families. In the 1990s, her office set up an entirely new, “more collaborative” court system to deal with ICWA cases, with specialized judges, attorneys, and a stronger connection with the tribes.

“What's unfortunate is that it hasn't really moved the dial, when we're looking at the percentages of the disparities,” says McKeig.

Indeed, the most recent data show that reforms have barely moved the needle. From 2015 to 2019, the disparities in out-of-home placement rates between Native and white families have declined by only a fraction of a percentage point, according to annual Minnesota Department of Human Services reports.

In Hennepin and neighboring Ramsey County, court monitors like Sadie Hart have recently been brought in to ensure that ICWA cases are properly adjudicated—a change that has seen some success, according to Hart. “Ramsey County is finally recognizing the damage that they've done to the community. And they're taking responsibility for that,” Hart says. “It's still in the really early stages, but they're making good efforts.”

Still, farther outside of the Twin Cities, in places like Beltrami County, Hart says there hasn’t been much movement on ICWA compliance. Often she worries that social workers may just be ticking boxes, a concern shared by several of the experts interviewed by The Fuller Project.

“People don't know that this is what they're supposed to be doing, or they don't have the time to do what they're supposed to be doing,” Hart says.

Another recent state initiative is the American Indian Families Grant Program, which started in 2020 and provides early interventions and direct support to Native families. Participation is promising so far, says Brown.

MartinRogers, whose research is focused on the Native community in Minnesota, is skeptical that the system can be changed from within. “I think that some people would probably say that the system was designed to do exactly what it’s doing,'' she says. “So it’s probably not going to be able to fix itself.”

Still, more programs that enable parents dealing with issues like chemical dependency or housing insecurity to remain with their children would be huge, MartinRogers says. Advocates of reform like Senator Kunesh argue that properly educating judges and county officials on ICWA and holding them accountable through more rigorous audits are necessary to push the ball forward.

Addressing inherent issues with the mandated reporter system would also go a long way, says Malaika Eban, a social worker, and director of community strategy at The Legal Rights Center. In Hennepin, most child welfare reports come from mandated reporters, according to Hennepin County Human Services. Eban says these reporters, many of whom are educators, are often uninformed about what happens after they make a report.

“I think that many folks who are mandated reporters… think, ‘OK, I call child protective services, someone goes and checks in on the child, if nothing’s wrong, then no problem. Everybody goes on with their life,’” says Eban. “But that’s not the reality.”

Because CPS intervention can cause parents to lose jobs and housing and create trauma even if a child is never removed from the home, Eban recommends giving mandated reporters better training.

As a social worker herself, Eban says she believes that most people involved in the child welfare system truly want what’s best for families, but the system is too big, with negative historical roots that run too deep, for any one individual with positive intentions to change it.

“Until every single social worker is willing to acknowledge that reality, then we’re going to see the results that we have,” Eban says.

Giving tribes autonomy over child welfare issues affecting their citizens, and fully funding tribal child welfare programs, as intended by the ICWA, would also do a lot to address these issues, says Jacobs.

District court Judge Terri Yellowhammer, a member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, who first started working on ICWA cases in the late ‘90s, knows fixing these issues won’t happen overnight.

“I think we have to think about it in terms of steps,” Yellowhammer says. “Otherwise it’s overwhelming, it's like a 1,000-pound boulder. You have to start somewhere.”

In Minneapolis with her two children, Teresa Nord remains skeptical that much can be done to fix the system that upended her life. “There absolutely needs, in my mind, to be a complete system abolishment,” Nord says. “It can’t continue the way it is. Because more and more and more… families are destroyed.”

Correction: A previous version of this story misstated the amount of time Teresa Nord spent in prison and how long it took for her to regain custody of her daughter. She served two years’ time and spent three years regaining custody.

Support for this reporting was provided by the USC Annenberg School of Communications and Journalism National Health Journalism Fellowship.

[This story was originally published by Mother Jones.]