How South Dakota voters could help save the lives of uninsured moms

The story was originally published in PBS NEWSHOUR with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2022 National Fellowship

The only times Veronica Olds, 30, has had health insurance across the last dozen years has been when she is pregnant. A mother of two girls, with a baby boy on the way, Olds carries some medical debt and may have other health problems, but says those issues are “just gonna get put on the backburner.” Medicaid expansion could help Olds and other mothers in South Dakota provide medical care for their children and themselves.

Photo by Hope Schumacker for the PBS NewsHour

RAPID CITY, S.D. – Cassandra Big Crow was strapped to a gurney as paramedics slid her into the belly of a yellow and blue helicopter, its blades whisking the air.

At 37 weeks pregnant, she was so thrilled to meet her little boy that she had painted her finger and toenails baby blue. But now, as life-saving equipment beeped and blinked inches from her nose, Big Crow’s mind spun at what this unexpected medical emergency might cost her, an uninsured South Dakotan living in a maternal health desert.

Hours earlier, she had driven 90 miles from her mother’s home near Rapid City for a prenatal appointment at the hospital near her grandfather’s house on the Pine Ridge Reservation. She felt dizzy and her vision was blurred, but Big Crow was in a hurry. Hospital staff took one look at her painfully swollen legs, checked her blood pressure and panicked. She might have a seizure, they said, and she needed to be airlifted back to the city from which she had just come for further medical care.

Over the deafening whir of the helicopter, her tears and concerns about her own health and safety, Big Crow asked the flight medics who their employer was, and if their service was covered.

“The main thing that was in my head was, ‘This bill is going to be so huge.'”

“The main thing that was in my head was, ‘This bill is going to be so huge,’” Big Crow said.

In a matter of days, her fears were validated.

If she had only qualified for Medicaid, things might have gone differently. An independent contractor who audits workers’ compensation claims for insurance, Big Crow had applied for coverage after she got pregnant, but was told she earned too much money.

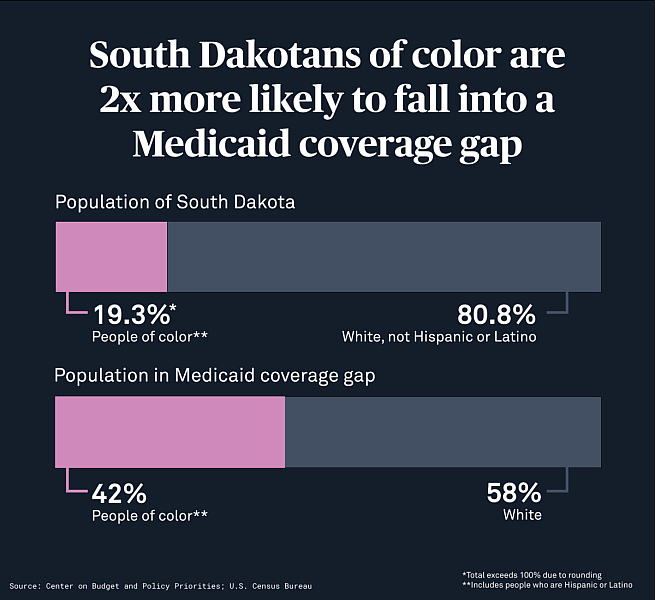

Big Crow isn’t alone. One out of 10 South Dakotans don’t have health insurance, according to the Census Bureau. Across her state, 16,000 adults are uninsured because they can’t afford private coverage, but their incomes disqualify them from Medicaid – what’s called the Medicaid coverage gap. While eight out of 10 state residents are white, South Dakotans of color are twice as likely to end up in the Medicaid coverage gap.

But soon, on Election Day, South Dakota voters will decide if they want to expand Medicaid, allowing more than 40,000 people a chance to enroll. It’s a move that could potentially save patients’ lives, according to doctors in the state who spoke to the PBS NewsHour.

Graphic by Jenna Cohen

Three out of 10 South Dakota births are funded by Medicaid, ranking it among the largest payers covering births in the state. (Nationwide, it’s a bit higher – the federal public health insurance program pays for four out of 10 births.)Some parents qualify for Medicaid in South Dakota during pregnancy, but that care can be riddled with caveats, and it ends 60 days after delivery unless the postpartum patient develops a disability or remains qualified for other reasons, according to the South Dakota Department of Social Services. In 2020, one out of seven women of childbearing age were uninsured in the state.

After Veronica Olds aged out of South Dakota’s Medicaid coverage, the only times she has had health insurance across the last dozen years was during her four pregnancies, including one that ended in miscarriage.

Over the last decade, she has wrestled with depression and anxiety without reliable access to help when she needs it. She developed sciatica when she was pregnant with her older daughter, age 4, and severe hip pain with her younger daughter, now 2. Medicaid covered her trips to see a chiropractor during both pregnancies, but in between, she has to pretend like the problems aren’t there. She waited months with painful cavities eroding her molars and ignored concerns about her thyroid before turning to the Community Health Center of the Black Hills, a federally funded facility that cares for underserved communities at potentially little cost to the patient. But heightened demand for services can mean long wait times, and the staff there can only do so much, Olds, 30, said.

“How do you expect somebody to be a productive member of society if they’re not healthy?”

“If it’s something they can’t handle, they still have to send you to the ER and then you’ve got an ER bill,” Olds said.

Dr. Katherine Degen, an obstetrician and gynecologist in the area, said so many of her patients are “just struggling to be good moms” and “put themselves on the backburner.” They may ignore undiagnosed (or untreated) diabetes, hypertension or other chronic conditions because reining them in would cost money they don’t have. As a result, Degen said, “They die early, or they’re not fully available to their families at the extent they would like to be.”

“How do you expect somebody to be a productive member of society if they’re not healthy?” Degen said.

Before former President Barack Obama signed the Affordable Care Act into law in 2010, a quarter of women of reproductive age in the U.S. were uninsured, said Jamie Daw, assistant professor on health policy and management at Columbia University. Since then, most states have accepted federal money to make Medicaid – and health care – more accessible and nearly cut in half the percent of uninsured women in this age group.

But South Dakota is one of 12 that has not expanded Medicaid. There, people can sign up only if they become pregnant, have dependent children, live with a disability or are elderly, though income requirements further erode those categories. No other adult under age 64 can qualify for Medicaid in South Dakota. Even among pregnant people, the state has the strictest income limits for Medicaid. Applicants have to make no more than 138 percent above the federal poverty line, which adds up to less than $18,000. After the Supreme Court overturned federal protections for abortion, South Dakota’s trigger ban immediately went into effect. Degen fears the state’s restrictions on abortion make it likely more people will carry pregnancies to term, regardless of whether or not they can physically or financially afford to do so.

Cassandra Big Crow, 29, has always wanted to be a mother, to “feel like I have purpose.” She applied for Medicaid when she became pregnant, but state officials denied her request because of her income as an independent contractor. Even among pregnant people, the state has the strictest income limits in the U.S. for Medicaid. Applicants have to make no more than 138 percent above the federal poverty line, which is less than $18,000. Photo by Hope Schumacker for the PBS NewsHour

Most clinics in Rapid City only accept patients who either have private insurance, have already been approved to receive Medicaid or can provide money upfront, said Jennifer Sobolik, a certified nurse practitioner. Everybody else goes to community health providers like herself – if they seek out reproductive health care at all.

When, recently, one of her patients didn’t show up for a prenatal appointment, Sobolik realized the patient had just turned 18, aging her out of Medicaid. Even though Community Health Center of the Black Hills asks patients to pay on a sliding scale, the prospect of being on the hook for a medical bill can be intimidating enough to discourage people from darkening the door of their care provider.

“If you’re a person in a situation where you’re deciding between eating or seeing the doctor, you’re probably going to choose having your next meal,” she said.

How patients fall into coverage gaps

The fact that states have such different rules around Medicaid has divided entire populations of people into an unwitting experiment, one that reveals the community-wide value of access to health care.

People in expansion states are more likely to have health care coverage and see doctors for routine preventative care, while facilities in under-resourced areas are more likely to remain open. In non-expansion states, people are more likely to remain uninsured and wait to seek care in order to avoid steep medical bills or because they are unable to travel long distances – that is, until their condition becomes an emergency and care becomes more complicated and costly. A September study published in the journal JAMA found people in non-expansion states were 40 percent more likely to incur medical debt than people in Medicaid expansion states.

Photo by Hope Schumacker for the PBS NewsHour $1 too much Brooke Pond, 27, knows it’s possible to work full-time and still be unable to afford health care close to home. When she was pregnant with her first child two years ago, she earned $13 an hour as a mental health counselor but made $1 too much annually to qualify for Medicaid, she said. “If I got insurance, I wouldn’t have much of a paycheck,” she said. She received coverage through the Indian Health Service, but she had to drive 100 miles during a snowy, South Dakota winter to reach Pine Ridge Hospital for a February delivery. It was “super stressful,” she said, and she “never had the same midwife.” She asked the hospital if she could give birth closer to her house. “‘It’s your first kid,'” she said officials told her. “‘You’ll have time to get here.'” That response did not fill her with confidence. Since then, Pond has a new job that offers her private health insurance, and is currently pregnant with her second child. She said if she had had Medicaid, she believes she would have felt less stressed and like she wasn’t "just being passed around."

Fear of financial ruin is enough to compel people to gamble with their health instead. In 2019, three out of 10 U.S. adults without insurance took that risk by skipping needed medical care to avoid costs. At the Community Health Center of the Black Hills, Tim Trithart said he and his staff encounter such patients on a daily basis. Patients with sporadic health coverage do not come in on a regular basis, missing out on preventative care, and show up when their needs become catastrophic, Trithart said.

“If you extend any sort of health coverage, you’re going to improve care, and you eliminate one of the barriers that people have,” he said. “People that don’t have access to care — they will avoid coming in.”

Bills – and lack of money to pay them – worry Olds the most. For seven years, Olds has lived in the same trailer next to a sweeping pasture where a rancher raises black Angus cattle. Her children love to feed watermelon scraps to the cows, who ultimately are destined for someone else’s plate. For the last year, prices have been so high that Olds hasn’t been able to afford ground beef herself. Right now, their $310 in lot rent gobbles up most of their money, leaving little for food, gas or utilities, let alone health care.

Life is unpredictable enough. Olds wishes that access to care didn’t have to be. In May, Olds’ husband was wearing protective goggles while cleaning asbestos from the ceiling where he works. While holding a broom with a sharpened handle, his ladder suddenly wobbled. He tried to catch himself, but his hand holding the broom bounced off a nearby wall. The sharpened handle jammed underneath his goggles, damaging his left eye. His job did not offer regular health insurance for himself or his family.

He has since undergone three surgeries and receives a weekly $570 check and health coverage – but only related to his eye injury – through worker’s compensation. Olds said her husband’s heart also troubles him, but if he sees a cardiologist, that will be one more bill the family can’t afford to pay.

A year ago, an inflamed cyst became so painful that Olds finally went to urgent care for relief, but the visit cost her more than $1,000.

Paying it off is “just not really feasible for us right now, so I’ve still got that bill hanging over my head,” she said. She suspects she has other health problems, too, but they are “just gonna get put on the backburner.”

“It would be real nice if [health insurance] was more than just the six-to-eight weeks after you have a baby,” Olds said. “There can be other pregnancy-related issues further down the road from that.”

For the better part of a decade, Jamie Daw and Lindsay Admon, an obstetrician and gynecologist at the University of Michigan, have studied what happens when people endure insurance churn – going in and out of health coverage – and what that means for their overall health. In 2017, Daw co-authored an article published in the journal Health Affairs where she and her colleagues analyzed nationally representative survey data from 2005 to 2013 and found high rates of insurance transition before and after a person delivered their baby.

The authors also concluded that “[h]aving health insurance facilitates women’s access to timely prenatal and postpartum care, which improves birth outcomes and supports the long-term health of women and newborns.”

The research went a long way to make reproductive health care more accessible. In 2021, Congress passed the Maternal Health Quality Improvement Act, designed to increase rural access to obstetric care. Earlier this year, the Biden administration urged all states to expand Medicaid so it would expire 12 months after delivery for all people who give birth, instead of the typical 60-days – a direct response to a growing body of research showing a majority of maternal deaths happen after childbirth. The administration pointed to Daw’s research in its June report, the White House Blueprint for Addressing the Maternal Health Crisis. So far, 36 states (including the District of Columbia) have extended their postpartum care beyond that 60-day limit. But South Dakota is among 15 states that have not taken up that year-long extension.

Health care providers told the NewsHour that the narrow window of postpartum coverage in South Dakota also means that many patients don’t have enough time or haven’t physically recovered sufficiently to schedule care that could prevent future pregnancies, such as tubal ligation, while they still have Medicaid coverage.

Policymakers have been cutting Medicaid postpartum benefits after 60 days “because the mom wasn’t the focus,” Daw said. And evidence suggests the problem of insurance churn will only worsen if policies and systems aren’t in place to help pregnant and postpartum people get timely and affordable access to the care they need, she explained.

“We have to change this. It wasn’t designed to support mom’s health.”

The difficult road to find care

Financial cost is not the only barrier to care in South Dakota. The state is widely regarded as one of the nation’s reproductive health deserts. Some of Degen’s patients drive up to four hours to reach her practice in Rapid City, a former frontier town that grew along the banks of Rapid Creek, nestled between the Black Hills and the Badlands.

On an early October day, moody gray clouds rumbled across an otherwise open blue sky, as golden prairie grass rolled like waves and bright yellow aspen leaves fluttered in the breeze. The road between Rapid City to Pine Ridge can be lovely – and treacherous.

In winter, a single storm can dump 2 feet of snow onto that same winding asphalt. In the spring, melting snow and heavy rains can flood the river’s banks and nearby roadways. The challenge of making the same trip without reliable access to a vehicle – either asking someone else for a ride or hoping your car survives the journey – can gnaw at one’s resolve. Add to that stress the need to find enough money to cover the fuel costs for a 180-mile round trip or to arrange care for a loved one. One of Degen’s patients once came to her, apologizing for being late to an appointment because a one-mile stretch of road near her house had washed out. Her brother had walked ahead of her car through the water to make sure the vehicle’s engine wouldn’t stall out.

“It’s awful what people go through to seek care,” Degen said. “These are people who do seek care.”

Dr. Katherine Degen, an OB-GYN at the Rapid City Medical Center in South Dakota, has patients who drive up to four hours to reach her. Those who show up in need of care are “the sickest patients and the most poorly cared for patients I can imagine,” Degen said. Photo by Hope Schumacker for the PBS NewsHour

Run with four other physicians, Degen’s office accepts all insurance, and clinicians from other facilities refer patients to her from across the state. The need for their services – and strain on providers like Degen – is only growing in rural U.S. counties, where access to obstetric care has declined over the last decade.

Research has shown that states without Medicaid expansion saw more rural hospitals close than states that expanded health care coverage. In turn, these closures trigger economic shocks in the communities that often relied on those facilities for health care and jobs. In Rapid City, the patients who show up in need of care are “the sickest patients and the most poorly cared for patients I can imagine,” Degen said. “It’s horrendous what people will live with because they have no access to health care, no transportation access and no resources in general.”

Throughout her pregnancy, Big Crow saw her midwife as often as she could afford. An enrolled member of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, Big Crow had a visit with Amanda Youngers, who provides patients with reproductive health care, has treated hundreds of women over the course of her career and works within the Indian Health Service (IHS) system. Knowing that Big Crow had been denied Medicaid coverage, Youngers recommended she look for options with ties to IHS. So the mom-to-be began to plan her delivery at Pine Ridge Hospital, which can be a nearly two-hour drive in ideal weather conditions.

Born and raised in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, Youngers became a midwife in 2008 and worked on the Pine Ridge Reservation for 14 years. One of the biggest issues she observed, along with fellow midwives and their patients, was the “need for consistency and continuity of care.” She saw dozens of midwives and obstetricians cycle through the system, leaving their jobs after they had paid off their student loans or if their circumstances compelled them to move on.

Many of Youngers’ patients lived with more than 10 family members in multi-generational households, where everyone in the home relied on a single, shared vehicle. While her patients often were eager to receive prenatal visits, she said those visits ranked lower in household priorities compared to a child or older relative’s doctor’s visit, or if a family member needed to drive to work. The picture of access grew even more complicated if a pregnant patient was diagnosed with chronic health conditions, such as diabetes or hypertension, and required visiting a specialist who traveled once a week to Rapid City.

“Those are real barriers that we saw every single day for patients,” Youngers said.

Lack of access to reproductive health care has tragic consequences. According to data compiled by maternal mortality review committees in 36 states (not including South Dakota), more than 80 percent of pregnancy-related deaths were preventable between 2017 and 2019. This September, a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that out of 1,018 deaths, the most common underlying issues included mental health conditions, hemorrhaging, heart-related conditions and infection. Native pregnant and postpartum people suffered and died at disproportionately higher rates compared to other groups; in those communities, 93 percent of such deaths didn’t have to happen.

In recent years, the United States finally began paying more attention to how often people died as a result of childbirth, Daw said. But there’s still more work to be done to make sure people have access to care when they need it.

“A lot of maternal deaths are preventable if they’re treated in a timely way,” Daw said. “Health insurance is important for timely treatment.”

Patients like Big Crow regularly make longer trips for health care because IHS – which covers more than 2.5 million American Indians and Alaska Natives and is often considered the last-stop insurer for Indigenous peoples in the U.S. – will not cover their services at the much closer IHS facility in Rapid City due to layers of bureaucratic rules.

According to Youngers, everything was fine during Big Crow’s last visit. But as her due date neared, Big Crow developed preeclampsia, which quickly worsened. During her drive to Pine Ridge, Big Crow said that so much fluid filled her calves that if you pressed your finger tip against them, the pale impression it left behind would take several seconds to disappear. As her health deteriorated, she was loaded onto the helicopter. She gave birth to her son weeks early and remained hospitalized for six days.

Big Crow thought she had done things correctly to avoid the costs and concerns that still ended up swarming her thoughts – the patient advocate from the same hospital that billed her thousands even affirmed that she had. Still, three weeks after her baby was born, Monument Health was “blowing up” her phone, Big Crow explained, calling repeatedly about paying for the $5,000 helicopter ride she reluctantly took. “It's a guessing game on if the tribe is going to pick up the bill, or if I'm going to be stuck with thousands in debt,” Big Crow said.

If IHS government officials don’t judge the visit to be “priority one” or a life-or-death emergency, then they will not cover the cost, said Ryan Jumping Eagle, who sits on the tribal council for the Oglala Sioux Tribe as a liaison to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. In July, tribal leaders came out in support of South Dakota’s Medicaid expansion, saying it would help patients have better access to care and would help cover unaffordable bills that go unpaid and tank people’s credit.

For five years, 29-year-old Big Crow has been rebuilding her credit after declaring bankruptcy for other circumstances. If IHS won’t cover it, she said, she would have to make payments in $800 monthly installments and take another five years to pay off the debt.She was worried this unexpected bill could jeopardize her hard work and haunt her for years to come.

The political fight over Medicaid expansion

On Nov. 8, South Dakotan voters will decide if they want to expand Medicaid or keep the status quo. If passed, Amendment D will go into effect in July, and the federal government will fund nearly all of the $300 million annual cost.

Some political experts said the first vote on this issue really came during the June primaries. In a Republican-backed proposal, voters were asked to raise the threshold for ballot initiatives that cost $10 million or more, meaning that successful referendums would need 60 percent support from voters to pass rather than a simple majority of 51 percent or more.Two-thirds of South Dakota votersrejected the constitutional amendment, which would have made it harder to pass Medicaid expansion.

A poll in early October found that about half of registered voters supported expanded access to Medicaid, and another quarter weren’t sure how they felt about the program. Overall, fewer than quarter of voters opposed the measure.

When it came to the state’s mood at that moment, “The ballot is in a very good position to be passed,” said political scientist David Wiltse, who also directs the SDSU Poll.

More than 80 percent of pregnancy-related deaths were preventable between 2017 and 2019.

But Sherry Bea Smith, a registered nurse and hospital administrator, has advocated for Medicaid expansion for months, and she thinks the vote is “gonna be a squeaker.” For years, she has spoken to potential voters at state fairs, or sat in on debates with lawmakers and now she feels the conversation around Medicaid expansion “is at a crescendo point.” The coronavirus pandemic and the economic instability that followed convinced more South Dakotans that they need to change their state’s fragmented health care system, Smith said, and she anticipates a “big voter turnout.” But if the citizen vote doesn’t expand Medicaid, Smith says advocates will return to the state legislature.

“It’s archaic that we have such an advanced society that doesn’t get a guarantee of care for well-being,” she said.

The poll found that while one out of five South Dakota voters oppose Medicaid expansion, that attitude was largely held among Republicans. Incumbent Gov. Kristi Noem, a Republican ally of former President Donald Trump (whose administration worked to repeal Medicaid expansion and the ACA), publicly rejects the premise that South Dakotans need Medicaid expansion, saying“single, able-bodied” people need to work “and have the potential to earn benefits that would pay their medical bills.”

In an August column published in the Rapid City Journal, State Rep. Trish Ladner, the Republican state legislator who represents a nearby district, said she thinks the push to cover more people’s health care “boils down to dollars and cents.”

Ladner pointed to the historic level of South Dakota-based health care providers and health-related organizations that have endorsed Medicaid expansion, saying, “Corporate entities, unless a non-profit, are not known for investing large amounts of dollars into something without expecting a return on their investment.”

In the partisan debate that embroiled the ACA’s eventual passage, opponents maintained that the system would financially drain the nation and its states with little to show for it. But dozens of states have expanded Medicaid, and experts say these doomsdaypredictions have not panned out.

Ladner did not respond to the NewsHour’s requests for comment. Noem’s reelection campaign pointed to the governor’s comments during a Sept. 30 televised debate.

From left to right: From Rapid City, the drive to Pine Ridge Reservation can be lovely, but it can take two hours even in the best weather. // Amanda Youngers, a certified nurse midwife, talks with patient Kalen Mehlhaff at IHS in Rapid City. Youngers worked on Pine Ridge for 14 years. Photos by Hope Schumacker for the PBS NewsHour

Across the nation, there will be a new wrinkle to the Medicaid gap problem come early 2023. Tens of millions of Americans are expected to lose their Medicaid coverage and will need to re-enroll in the program once the Biden administration lifts the coronavirus pandemic’s public health emergency. That declaration froze people’s Medicaid status so states could not drop them from coverage in the middle of a pandemic. This artificial buffer created one of the lowest rates of uninsurance in modern U.S. history –8 percent of the overall population. But when the emergency is lifted, health policy experts expect a deluge of uninsured adults and children – and foregone care – when people have to fill out and submit paperwork.

“I want him to be an early talker,” Big Crow said about her son, standing outside a gas station in Black Hawk, South Dakota. She likes to talk, so it makes sense she’d want her little boy to keep up with her. She says she reads “I Love You to the Moon and Back” to him and narrates her day to him as she works remotely from home. (“Now, I’m going to go wash my hands!”) When she turns to talk about how frequently he runs through diapers, the newborn lifts his head and coos at his doting mother, successfully changing the topic.

Holding him quietly curled in her arms, she unfolds his neatly kept, hospital-issued blanket as a cool breeze rushes past, wrapping it around his legs and toes and alligator-print onesie. Her fingers gently fuss over the soft baby fuzz on his left ear. In her arms, he doesn’t squirm or get agitated.

Yet for Big Crow, her son’s first month of life was an hour-by-hour struggle. She had trouble sleeping and constantly wrestled with anxiety over whether IHS would cover the cost of the helicopter ride.She grew frustrated thinking about who seems to skate through the system currently in place – people who are either wealthy enough to pay for unexpected expenses themselves, or who have virtually no income or assets and rely solely on the government for assistance.

“If you're in the middle area, you have to struggle to get by,” she said.

Over the next few weeks, as her body healed and her son grew, she called IHS repeatedly, desperate for updates about her bills. She and her grandfather mailed handwritten letters, pleading her case. She submitted her Medicaid denial letter and explained how the monthly payments she would owe cost as much as rent.

“There was no way I would’ve been able to afford that,” she said.

Then, in late October, she said an IHS official told her over the phone that the agency would cover her cost and intervene on her behalf with the hospital in Rapid City where she had been airlifted. She expected to see a letter arrive in the mail in days.

For the first time since before her son was born, Big Crow felt at ease – a calm that could only be broken by the next medical emergency.

The upcoming vote can’t erase the medical debt that already hangs over people who have been through similar crises. But Medicaid expansion would still help her and her son have more reliable and consistent access to affordable care in the future, she said.

This story was produced as part of a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 National Fellowship.