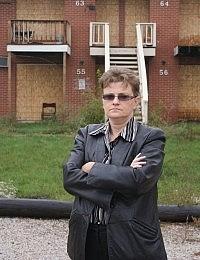

Julie Pryde is an "accidental advocate"

Julie Pryde, public health manager of Champaign-Urbana , was as surprised as ever when she went to the apartment complex Cherry Orchard Village to address a drainage issue, and found deplorable living conditions in the building. She immediately got to work and called an emergency meeting. She worked with residents, media, and state and local agencies to house the migrant workers in a hotel in Rantoul, Ill. The effort culminated in the closure of Cherry Orchard.

Julie Pryde, public health manager of Champaign-Urbana, has lived in the area all her life and has fond memories of shelled corn during the summers of her childhood.

Pryde was as surprised as ever when, in December 2009 she went to the apartment complex Cherry Orchard Village to address a drainage issue and found deplorable conditions in which people lived in the building.

Sewage flooded the land where housing complex once stood.

There were holes in the windows of apartments that opened directly out into the snow.

The apartments had no heat or electricity. People kept warm by keeping their oven doors open.

There had not been running water for a month, Pryde was told.

Electrical wires hung from the ceiling and there wer no carbon dioxide or smoke detectors.

What she saw in Cherry Orchard, struck Pryde.

She immediately got to work and called a emergency meeting on January 5, 2010. She worked with residents, media, and state and local agencies to bring the inhabitants of the compound, many of whom were migrants from Texas, to a hotel in Rantoul.

The effort culminated in the closure of Cherry Orchard.

Although the initial contact point Pryde had with the apartment complex was through her job responsibilities, her involvement ended up turning into something deeper and more personal.

Her illusions about the true nature of migrant labor were destroyed, and the system in which these people work and the companies responsible for their welfare became clear.

"They were new people now living in buildings like this," said Pryde."They were literally migrants who came from Texas by a foreman. Nobody wants to take any responsibility for putting people in this type of housing. People who get cheap workers do not have to look people in the face because they are brought by intermediaries."

"I looked people in the face and that changed me," said Pryde, who describes herself as an "accidental advocate."

"Once you see what happens, you can not go back," she said.

She has practiced this defense since that first winter visit to Cherry Orchard.

In early April, she convened a group of more than 20 people, from police, to academics from the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana, to providers of services for migrant workers and members of the community.

The purpose of the meeting was to discuss the best way to help migrant workers who were coming back to the area for corn shelling season that takes place in late June. Many of them stay until harvest in October.

The main emphasis in the group was to address the situation unfolding before them in their own communities, rather than waiting for state or federal authorities to resolve any problem. The group was created and tried to find solutions to a number of problems that had occurred the previous year.

The Urbana Police Chief, Patrick Connolly, said many migrant workers were attacked in the community on several occasions after cashing their paychecks. He praised the children of workers who tried to find the perpetrators and retaliate against those responsible for stealing the wages of their parents.

Connolly said he would like to find a local bank that could make the announcement, "We charge checks. Just do not do it here," referring to the area where there was rampant theft.

"There must be a solution," he said. "I do not know what would that be."

Some suggested solutions: request the credit union at the University of Illinois that would allow workers to cash their checks without an account.

Another possibility: partnering with public transit authorities to transport workers to a bank located in a Walmart in the area. Thus, workers could cash their check and make purchases on the same trip.

Pryde spoke frankly about the limited progress that had been reached with the closure of Cherry Orchard, but said she was optimistic about what the new group formed by members of the local people could do to help immigrants who come this year.

"We all join," said Pryde, emphasizing the sense of collective responsibility that permeates the group. "It is good to get to know eachother in advance."

This article was originally published in http://www.vivelohoy.com/