Latinos face mental health woes alone

Angela Maria Naso wrote this story while participating in the California Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of the Center for Health Journalism at USC’s Annenberg School of Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

Do Latinos have the necessary resources to treat their mental illnesses?

Many do not seek treatment due to the stigma or fear of being labeled as crazy. Others do not have the means to access the appropriate services to adequately manage their mental health needs.

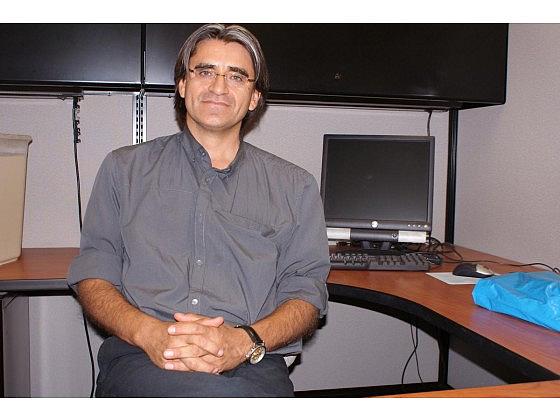

“Among the many obstacles that the Latino community faces, stigma is first, followed by distrust of government and religion,” said Alfredo Huerta, a Mexican immigrant with 18 years of experience as a clinical therapist for the Riverside University Health System’s Department of Behavioral Health.

While Huerta, of Beaumont, believes that there is an initial resistance to ask for help, once the family gets involved with the treatment, the stigma is reduced.

He’s not the only one who feels that way. Muñoz’s mother, Sara Muñoz, commented that in the Latino community, the tendency is to keep one’s personal problems inside.

“In our culture, acceptance is the hardest part. I saw it when I would take my son to the clinic and would talk to other parents who did not accept the fact that their son or daughter had a mental health issue even though they were cutting themselves, for example. We all knew we were there for the same reason,” she said. “That is why I ask, what do we gain for staying silent?”

WIDESPREAD PROBLEM

The statistics speak for themselves: 73 percent of Mexican-origin adults with a mental health disorder will not get the needed treatment. The problem of under-utilization is even higher among Mexican immigrants. According to a 2012 report titled “Community-Defined Solutions for Latino Mental Health Care Disparities” published by the UC Davis Center for Reducing Health Disparities, 85 percent of Mexican immigrants who needed services remained untreated.

Veronica Kelley, assistant director of the San Bernardino County Department of Behavioral Health, feels that few ask for the help they need due to stigma and fear of government. She also feels that adolescents are especially vulnerable to the effects of acculturation and assimilation on their families.

“Adolescents are seeing that the social norms they are being taught at home are not the same among their peers, such as respect for authority. This can cause them a lot of stress and anxiety,” she said.

A shortage in bicultural and bilingual therapists was another barrier, she said.

IMMIGRANT PARADOX

In the case of immigrants such as himself, Huerta does not find it strange that they suffer from trauma. Leaving one’s country of origin and moving to a new nation is difficult.

Surprisingly, the UC Davis report indicates that newly arrived immigrants tend to be in better mental health than people their same age who were born in the U.S. This has been coined the “immigrant paradox.”

However, the longer the immigrant stays in the country, the more possibilities that he or she will develop mental health problems. For Mexican immigrants, individuals living in the U.S. longer than 13 years have higher rates of mental illness than those with fewer years residing in the country. This decline is said to be attributed to changes in lifestyle, cultural practices, increased stress and new social norms.

The report also found that Latinos face generalized treatments that will not accommodate their linguistic or cultural needs. And if left untreated, mental illness symptoms tend to get worse with time, which eventually impacts relationships, work and daily life.

There are effective treatments for these illnesses, said Huerta, who personally recommends psychotherapy, medication and support groups.

PROFESSIONAL HELP

Huerta suggests that it might be time to see a mental health professional when someone has a conflict or recurring problem with no apparent solution. Other symptoms could include: difficulty in sleeping, appetite changes, mood swings, negative thoughts and lack of concern for one’s personal appearance.

“Talking to someone is an important first step,” he said. “If the person is a believer and goes to church, they could talk to their pastor or priest. If they have access to a primary-care physician, they could make an appointment to see if the problem is physical.”

If the doctor does not find anything wrong, then the patient may be referred to a mental health professional, Huerta added.

In Joe Muñoz’s case, a Latino counselor from the Victor Wraparound Program, who came to see him at his home and at school was one of the keys to his recovery. “The counselor helped me find the resources I needed, and he also talked to me and my family, which helped improve our communication.”

About a year ago, Joe Muñoz co-founded an organization called Youth Advocates United to Succeed to help youths like himself who are facing hardships in their lives that are affecting their mental health.

“Sometimes life throws us into the ocean and the waves seem to be pushing us further and further away from shore. Our goal is to save lives, like a lifeguard. We are reaching out and bringing back those people who feel alone.” he said.

Given his own struggles, Joe Muñoz is surprised that he was able to graduate from Riverside’s La Sierra High School in June. Recently he started classes at Riverside Community College, where he plans to study psychology, American Sign Language and improve his Spanish, which is his immigrant parents’ native language.

“I gave myself a chance”, he said. “I took a negative and made it into a positive.”

[This story was originally published by The Press Enterprise.]