Living Lonely Part 2: Unsettled refugees

Lois M. Collins wrote the "Living Lonely" series for the Deseret News as a 2013 National Health Journalism Fellow. In the series, she examines the health effects of loneliness. Other stories in this series include:

Bhutanese refugee Hari Koirala, right poses with his family. They had lived for many years in a refugee camp in Nepal. Credit: Hari Koirala family photo

Hari Koirala’s parents were lonely in their native Bhutan because of government oppression. Then they were lonely for years in a Nepalese refugee camp, unable either to integrate into the camp or to go back home.

So it is no wonder, he said, that they are lonely here in the United States, where they resettled five years ago. They have lost their language, their country and many of their connections.

Still, Koirala sees a bit of joy awakening when his mom and dad plant and harvest on the farm the International Rescue Committee runs in Salt Lake County.

There’s something elemental and comforting about working the dirt with fingers and tools. Refugees often tell Grace Henley, who directs the IRC New Roots program, that it is the first experience that has felt like home to them for many, many years.

Social isolation, sadness, fear and often loneliness lurk in the very definition of “refugee.” People flee their country because of persecution — actual or feared. They are targeted for their race, religion, ethnicity or politics. War and violence are part of their world.

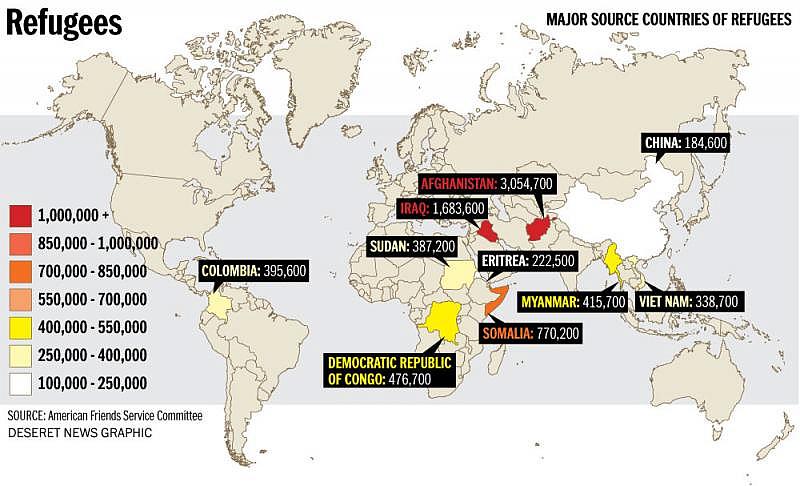

Some 42 million individuals, mostly women and children, are displaced: One-third of them are now refugees. The IRC and United Nations say war has uprooted one in every 170 people worldwide.

Isolation is “actually a pretty good defense if you’re fleeing for your life,” said Patrick Poulin, director of Salt Lake’s IRC office. But in a new land where one needs to meet others, learn the language and navigate society, what has been a tool becomes a barrier.

Today, the Deseret News continues a three-part series on the health impacts of loneliness and social isolation with a look at refugees. Experts say that refugees’ loneliness creates setbacks amid already-daunting challenges.

Homesickness is sickness

It’s called “homesickness” for a reason. The disconnectedness that occurs when one leaves home can wreak havoc on one’s health. Colonial Americans talked openly about its dangers. In the 1800s, you could die of “nostalgia,” said Susan J. Matt, history professor at Weber State University in Ogden and author of “Homesickness: An American History.”

Being far from the people and place you loved was said to cause dysentery, fever and heart palpitations. Union soldiers died of homesickness in the Civil War, while thousands suffered but survived. Some said homesickness caused rapid breathing, bad coughing, throbbing arteries and incontinence; others said it just made symptoms worse. By the second half of the 1900s, though, one had to suck it up. Being too dependent on kin and home indicated immaturity.

For refugees, homesickness and loneliness are often inseparable — symptoms hard to untangle. Refugees in the throes of loneliness and social isolation may suffer depression, lethargy, headaches, exhaustion and more. It makes it harder to learn needed skills like language or the logistics of survival in a new culture.

But as the United States accepts refugees from troubled regions, its policies can hurt and isolate refugees. The example Matt uses is of Vietnamese refugees in the 1960s and '70s. The federal government attempted to scatter refugees in the United States so that no single state had too great a burden. That lowered costs for states but kept many refugees from growing close to each other, she said. The policies “were remarkably inattentive to the social and psychological needs of those in exile from home.”

Martha Poage described something similar in the book “The Moving Survival Guide.” “I have made friends only to lose most of them each time I moved, decorated houses only to sell them the following year. When my children lost their friends and social standing in school, I lost my identity. I have been elated over some moves and cried over others. I have been lonely and isolated many times.” She moved for her husband’s career, not to flee for her life, perhaps leaving her homeland forever, Matt said. For immigrants, the return-home rate is between 20 and 40 percent. Refugees have to make it work somehow or return to danger. But they don’t always thrive.

Proven health impacts

In the book “Loneliness,” authors John T. Cacioppo of the University of Chicago and science writer William Patrick document the health risks of loneliness. It can depress the immune system, which in turn links to high blood pressure, stress hormones, impaired sleep and decision-making, obesity, mental illness, substance abuse and even dementia. Ohio State University researchers cite links to Type 2 diabetes, inflammation, heart disease, arthritis, frailty and what they call “functional decline.”

Individuals who work with refugees have seen the havoc. Refugees are under pressure to do well and learn to support themselves; safety-net programs don’t usually last long, Poulin said. At first, refugees have access to mental health and medical screenings and treatments. The results show anxiety and depression are common. But dealing with them may clash with language and cultural taboos. Even what mental health means differs among cultures. There may be religious and familial implications that Americans don’t see.

“They are so lonely and separated,” Matt said. “I think it is a real tragedy and it gets worse: You can’t talk about it. If there are taboos and you can’t talk about it, you just feel more of that emotion.”

Different cultures and challenges

Image

Tatjana Micic, an IRC immigration specialist, thinks that the ability of refugees to join existing communities depends upon where they come from and how their journey unfolded. The United Nations said some refugees come from well-run camps, while others have makeshift shelters or live on the street.

Those in camps may already know people when they arrive in a resettlement country. Having lived in community may also make it easier when two or three singles are placed in an apartment together to share expenses and keep each other company. It is difficult for a refugee to afford living alone.

But age and other factors matter, too, said Micic, a former refugee from Bosnia who arrived in 1997. Most children pick up English quickly and become translators for their parents. Elderly refugees move slowly in fitting in. Many are from war-torn countries and a lot have post-traumatic stress disorder, something that occurs increasingly in younger refugees, too. Elders are less likely to ask for mental health services.

Hari Koirala was 23 when he came to America — slightly after his parents. He has a wife, a little girl and has adapted well to work and life here. But he’s sad as he watches his parents’ generation struggle. What holds older refugees back varies from culture to culture, but the result is remarkably similar.

Aden Batar came from Somalia almost 20 years ago. Now director of refugee resettlement for Catholic Community Services of Utah, he said many Somalis come here as single moms with children. The concept of mental health is foreign to them. They don’t know how to ask for or accept mental health services.

Henley, Micic and others easily think of refugees who are lonely, who struggle to fit in, who grieve for former lives or worry how they will adapt. It’s much harder, they said, to get someone to speak openly about their experiences. That willingness is found only among those who are doing well, years after arriving. “The more you feel you don’t have value in the new community and don’t understand how it functions, the more hopeless you feel and less able you are to step out or to talk about it,” Henley said.

Image

Women of the World founder Samira Harnish, right, delivers bedding to refugee Ngakoutou in Salt Lake City Wednesday, Dec. 11, 2013. Harnish came to America from Iraq in the 1970s.

Women who struggle

Women of the World founder Samira Harnish, right, delivers bedding to refugee Ngakoutou in Salt Lake City Wednesday, Dec. 11, 2013. Harnish came to America from Iraq in the 1970s.

Iraqi and African refugee women are among the loneliest and most isolated, said Samira Harnish, who founded Women of the World four years ago to help refugees adapt to America. She’s done this work almost since she came from Iraq more than 30 years ago: young, scared and in an arranged marriage that didn’t last.

Women she helps may have survived combinations of war, oppression, honor killings, female genital mutilation, assaults and astounding poverty. “When they come to our country, they get isolated because of the language, what they don’t know about the law, the regulations, the culture. They are lost. I have many ladies who struggle with PTSD.”

Here, some lose children to gangs that speak English, which the women don’t understand. Some husbands, frustrated in their new lives, batter their wives.

The effects of loneliness vary, partly based on how long it lasts. Harnish describes one woman who lost weight and was too tired and fretful to sleep at night. She actually shook. Women of the World brought a volunteer in for English lessons and promised to teach her to ride the bus. It took time, but the day she left her house, Harnish said, “We cheered like you would for a kid when he walks the first step.”

When refugee assistance programs try to figure how best to use limited resources, loneliness and difficulty adapting are two things that do get attention, Henley said. They look especially hard at people who arrived alone or those who experienced a large number of challenges.

Grieving what’s lost

One of IRC’s Sudanese farmers attended agriculture school back home. He left, mid-schooling, when his village was attacked and his mother killed. He’d learned to farm at his dad’s knee and, as was tradition, received a tiny piece of land when he came of age. Arriving in America meant saying goodbye forever to that piece of land.

He is a strong man who got a good job and supports his family. He learned English and adapted fast. “He’s happy here,” Henley said, “But he still needed to grieve what he let go of. That’s true of almost everybody.”

Refugees who find a clear path to follow feel less lonely, she said. “If they come here without a clear jumping-off point, struggle with the language, can’t find a place to worship and don’t land in a strong community, it is much harder. Grief, loneliness and fear are more overwhelming.”

Matt believes it must be acceptable to feel loneliness, homesickness, and even garden-variety sadness. If people lost the pressure to repress unhappy feelings, “that itself might bring some relief. … I am reluctant to say that anything is hard-wired into us. But the need for human connections is pretty close to universal,” she said.

Making the best

When Gyanu Dulal arrived from Bhutan in 2008 with his wife and children, now 16 and 19, he found American culture and processes hard to fathom. Families that find community and someone to guide them do best, he said. He now works with other refugees through IRC.

Batar said churches, community groups and individuals can help. Catholic parishes often adopt CCS families from the beginning, welcoming them at the airport, setting up apartments, providing food and friendship despite language and cultural barriers. Caring is powerful medicine against loneliness.

Still, “every refugee gets homesick,” Batar said. Two weeks ago, a young single mom with two young children arrived from Africa in the middle of a blizzard. “I cannot stay here,” she said, shivering in unfamiliar cold. “I told her there will be days that will be warm in Utah. We will help you get used to this weather.”

Other pieces are harder: To thrive, she needs friends, a place to worship, people who understand her. Almost all feel depressed at the beginning. Mental health barriers are harder to overcome than physical ones.

Suhad Khudhair knows that. She fled kidnappings and killings in Iraq with her sons, now 15 and 21, in 2006. They reached Utah in 2009. It was midnight and the streets were empty. So was their apartment. The littlest one wept.

“We had no choice,” said Khudhair, who had studied English. “We had to survive or go back to a very bad situation.” She had never been so cold, couldn’t figure out buses, often got lost. They walked most places. Those things were manageable, but it was hard to make friends. They had left a big house, a car, a backyard, good jobs. Sometimes, she broke down and cried.

Curiosity took her to a nearby church where she made an unexpected friend who introduced her to neighbors and local customs. Eventually, Khudhair bought a small car. She now works at Catholic Community Services. Next year, she will apply for citizenship.

Dulal said those who get out and become active are less likely to become sick. One who doesn’t go out “sooner or later will have so many health problems — not just physical, but mental, too.” If they can become active in their culture communities, it helps. In camps, refugees often visit; here they may feel cut off. “We do not see any immediate solutions for that.”

Henley describes baby steps: One working in a garden program may learn English to talk about how to grow things. Or learn to ride the bus to go there more often. Eventually, he may want a phone. The steps one takes matter.

“I’m not sure anyone chooses loneliness,” Poulin says. “It’s like overeating; one’s not choosing obesity, but it’s an outcome.”

This story was originally published in the Deseret News.

Photos and video by Jeffrey D. Allred