For migrants, cultural barriers, life’s shocks complicate welfare cases

Perla Trevizo is a recipient of the University of Southern California Annenberg Center's Fund for Journalism on Child Well-being.

Other stories in this series include:

Part 1: Arizona Daily Star special investigation: Fixing our foster care crisis

Part 2: Despite state progress in Arizona, 'a lot of desperation, isolation'

Part 3: Hard work of reunification often entails rehab, intensive home services

Reporters reveal deep faults in Arizona’s swollen foster care system

Shared goals, collaboration are keys to family success

Moments of high anxiety for deported dad on custody quest

Racial and ethnic disparities in child removals go unaddressed here

When a parent is deported, path to reunion starts with Pima County group

Barreras culturales, obstáculo para el bienestar infantil entre inmigrantes

Se unen para derribar muros para padres deportados

La ansiedad de un padre deportado peleando por la custodia de sus hijos

Arizona no atiende la disparidad étnica en niños bajo cuidado temporal

Metas compartidas y colaboración son claves para que las familias tengan éxito

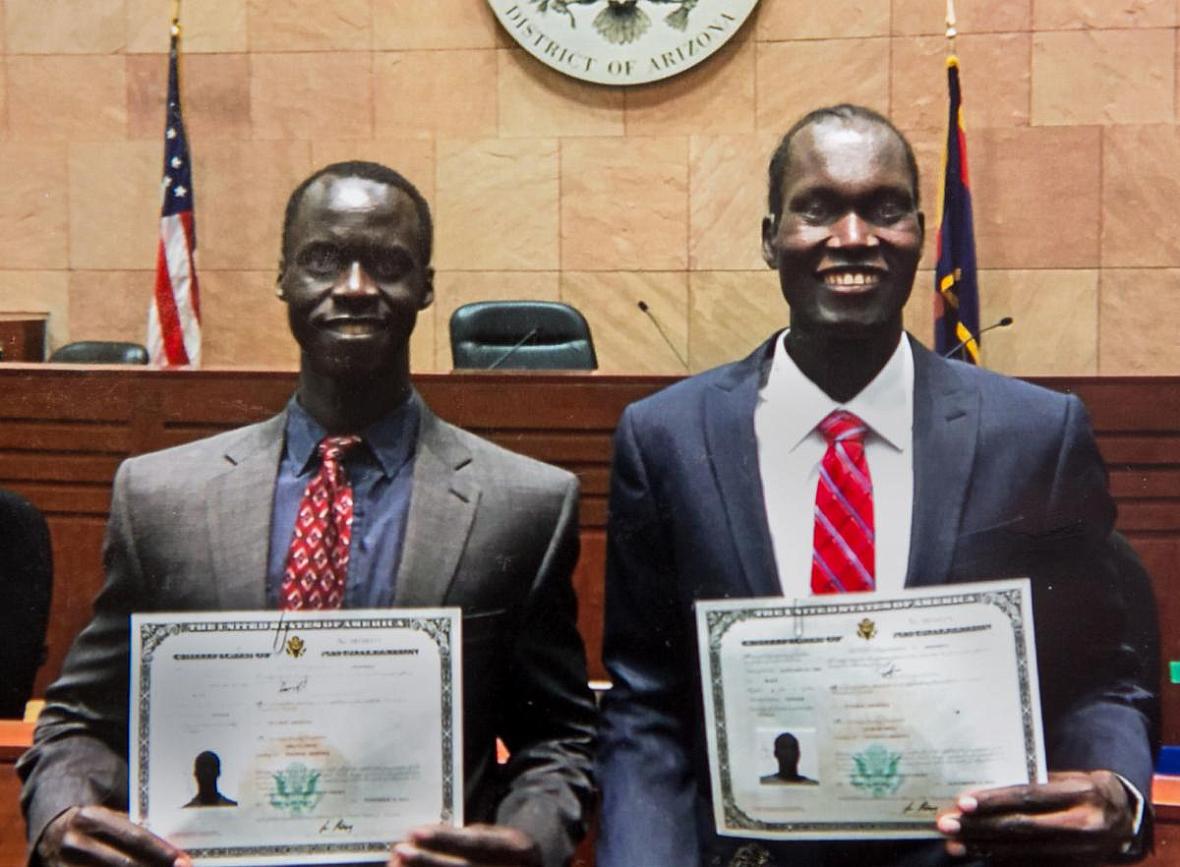

Obang and Ochor Odol were fostered by Deanna Campos, the principal at Wright Elementary School in Tucson.

(Photo Credit: Deanna Campos)

The woman fled danger in Eastern Africa and spent years in a refugee camp in Ethiopia, and the horrors she experienced left her unable to safely parent her children.

So one day in 2009, four years after their arrival in the United States, Ochor and Obang Odol, then 16 and 12, were asked to pick up their belongings as state workers waited and their mother watched. The brothers were not sure whether she understood what was happening.

The Department of Child Safety doesn't track how many children removed from their homes arrived here as refugees. A 2010 report found that children of immigrants in general represent 8.6 percent of those who come to the attention of the child welfare system nationwide. But as overall numbers of immigrant children or those with a foreign-born parent grow, child welfare workers serve a wider spectrum of families — some they can’t directly communicate with and some reeling from severe trauma.

While arriving as a refugee or being an immigrant doesn’t mean parents are more likely to abuse or neglect their children, their circumstances sometimes put them in a precarious position. Trauma, often the result of violence or sexual assault in their home country or on their journey to the U.S., along with language barriers, cultural differences, higher levels of poverty and, for some, lack of legal immigration status, can all be high-risk factors.

And once family members get involved in the child welfare system, they may face challenges that add a layer of complexity — exacerbated in places with high caseloads and caseworker turnover rates, as was until recently the case in Arizona. This can extend the time a child is in foster care or even contribute to the parents' rights being severed, experts said.

"It's really scary to be involved with DCS," said Meheria Habibi, resettlement supervisor with the International Rescue Committee in Tucson. "In the first place, they already have a fear that DCS will take their children away and on top of that you add the language barrier and not understanding the system."

Ochor Odol, then 17, joked around with Kathy Teel, left, and Deanna Campos at Amphitheater High in 2010. Teel and Campos were guardians of Ochor and his younger brother. (Photo Credit: Mamta Popat/Arizona Daily Star)

Trouble with English

Language is generally the top barrier for families with foreign-born parents.

Ochor, now 25 years old, remembers arriving in Tucson in 2005 and feeling lost.

“I didn’t know how to use electronics or the PIN number for the (debit) card,” he said. “If you don’t know how to read well, it’s hard, you can miss payments.”

He and his brother eventually learned but say their mother didn't.

Refugees get a "welcome guide" with information about life in the United States, which includes a section about physical abuse and neglect and how the government can take their children away.

During the first few months, refugee resettlement agencies help families by arranging for housing, filling out government forms, informing them about job opportunities and trying to guide them. But the goal of the program is for families to be self-sufficient as soon as possible.

Many adapt well to their new surroundings and with time learn English, get jobs and open businesses. But others struggle.

Children or other family members are often left to interpret.

No one in Arizona spoke the Odols' native language. When Child Protective Services, now DCS, got involved, they called a man in Minnesota to assist, Obang said. For everything else, interpreting was up to Obang, now 21 and a university student.

The Odols are members of the Anuak tribe of Ethiopia and South Sudan. A 2010 Arizona Daily Star story said their father was shot and killed in an altercation and their mother stricken with an infection that hampered her thinking.

“Mom didn’t talk about it much,” Ochor said. “She would just keep things to herself.”

PTSD is common among refugees, but behavioral health services here are limited, service providers say.

As their mother's health declined, she hid cereal boxes, threw things at her children and took their books, said Deanna Campos, the Odols' foster mother and Ochor's former teacher. "She needed a community of people to help her." But she was alone.

Akello never regained custody of her sons. She died in 2013.

Deanna Campos (Photo Credit: Ron Medvescek/Arizona Daily Star)

"A lot of times because of lack of access to language appropriate services, families fail to follow up with what's required of them to do and that leads to worse and worse scenarios," Habibi said.

In fiscal 2017, DCS got 3,600 requests for interpreters, often in Spanish, Arabic, Farsi and Swahili. Almost 200 of 2,700 DCS employees have passed a test and agreed to perform translation services in exchange for a stipend, with Spanish being the top language.

In 2014, DCS also implemented a policy to address clients' limited English proficiency that includes an assessment of services provided, languages needed and evaluation of compliance. It is also supposed to translate vital documents, among other requirements.

DCS did not respond to repeated requests to discuss how the policy was being implemented or to provide copies of the reports.

Some families are illiterate in their native language, but oral translation isn't always possible. Even taking parenting classes can be a challenge if families need an interpreter at every session.

"Native-born English-speaking parents have a difficult time navigating the child welfare system where there are multiple attorneys, caseworkers from a variety of service providers, meetings, court hearings, therapy sessions, parent-child visitations, parenting education classes and a new vocabulary of legal terms that even experienced lawyers are not familiar with," said Rebecca Curtiss, staff attorney at the Arizona-based Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project. "Imagine learning a whole legal process which your culture might not contemplate in the same manner. Imagine that your language does not contain words that accurately describe the concepts found in the U.S. child welfare system."

Looking back, Obang said, “I think if we had somebody who had spoken our language, that would have made the whole process a lot better.”

In recent years, government agencies and nonprofits have developed tools to help those working with refugee and immigrant families. Newly hired DCS specialists receive cultural awareness training designed so they "understand their clients — including foster and adoptive parents and the children in their care — in the context of their culture, and develop a sensitivity to cultural differences."

Fear of detention

Fear can also hinder the path toward reunification — fear of officials, of a new system, and for those in the country without status, fear of deportation.

One caseworker said families often associated them with immigration enforcement, which made their jobs more difficult, according to the 2011 University of Arizona study "Disappearing Parents: A Report on Immigration Enforcement and the Child Welfare System."

That fear can mean children in immigrant families are less likely to come into contact with social services whose workers serve as mandated reporters, said Alan Detlaff, dean at the University of Houston Graduate College of Social Work. People in immigrant communities may also be hesitant to report child abuse because of potential repercussions to families if members are undocumented, Detlaff said.

The Pima County Juvenile Court doesn't explicitly ask about immigration status, but judges have said it often comes up in child welfare department reports because it impacts the undocumented parents' access to services and employment prospects. A judge cited in the 2011 UA report noted an increase in cases in which immigration issues arise, with more than 25 percent of his cases then involving immigration issues.

Sometimes this fear can translate to a child not being able to reunite with the parent. In the UA report, a judge described a case where the child was left with the mother's sister after she was deported.

DCS approved visitations with the father in Texas but the man, who was in the country illegally, was afraid to take the bus to Tucson.

“It’s really heartbreaking. It’s a real dilemma," the judge said. "I wanted to make sure it wasn’t a financial barrier and he said, ‘No, I’m afraid that if I get on a bus I’ll be stopped and I’ll be detained.’”

[This story was originally published by Arizona Daily Star.]