'No access': Poor, isolated and forgotten, kids of 32304 see their health care compromised

This story was produced as a project for the 2019 National Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

13 million missed meals in Leon: 'Meal Deficit Metric' aims to track hunger across Florida

Coronavirus: Lack of access to tests hampers care in Tallahassee's poorer neighborhoods

Going granular: Why deep dives into health data can help kids in poor zip codes like 32304

At 32304's Riley Elementary, staff 'serve a greater need than just educating the mind'

Distanced from assistance: Rampant health problems in Gadsden mirror coronavirus risk factors

‘Our kids aren’t growing up’: Epidemic of gun violence scars, kills Tallahassee’s Black children

An afternoon inside the trailer of Michelle Kirkland, her husband Brandon Hughes and their two children Vivianna, 9, and Brandon

When Kisha Simms’ teenage daughter needed root canals and tooth extractions, the Publix deli worker made the four-hour roundtrip drive to Panama City for a consultation, appointments and follow-ups. No dentists in Tallahassee accepted her state insurance to perform the simple procedures.

A few miles away, Myssty Ochoa’s 8-year-old son Romeo walks around his family’s trailer on his toes. He needs casts to straighten out his legs. Doctors suspect the crippling disorder may be caused by an underlying medical problem, but his mom can’t afford X-rays to find out. Medicaid only pays for half.

Just a few months ago, Michelle Kirkland, Brandon Hughes and their two children were finally able to ditch the roach-infested trailer they lived in for four years. They moved into another mobile home off Highway 20, then the coronavirus hit.

Kirkland lost her job as a retail inventory worker at the start of the crisis. Her husband, laid off earlier when Winn-Dixie shuttered, saw his new work refurbishing restaurant equipment evaporate. They aren’t sure how they will make the $450 monthly rent and budget for nutritious food.

Simms, Ochoa and Kirkland all live in 32304, a zip code thrust into the spotlight when the state Chamber of Commerce last year highlighted its extreme poverty in a report to local economic leaders.

Scattered throughout Tallahassee’s distinct quadrants are well-known pockets of poverty, such as Frenchtown, South City and the Bond Community, where neighborhood advocates have formed alliances and task forces to try to improve conditions.

But the many impoverished enclaves of westward Tallahassee’s 32304 remain largely forgotten.

Few city residents can pinpoint the location of the oblong-shaped zone that begins a mile shy of the state Capitol, stretches west from the edges of Greater Frenchtown and Griffin Heights to U.S. 20 and the Ochlocknee River. Divided by U.S. 90, the area is sandwiched between West Tharpe Street and Jackson Bluff Road.

Past Collegetown, 32304’s many tarnished trailers and houses are on back roads hidden behind supply warehouses on the city's far west fringes. Laundry is strung along chain-link fences, parents walk home from the West Tennessee Street Walmart carrying groceries. There are barely any parks.

Almost 50% of children in 32304 live in poverty. And more than 9,000 households there subsist below the poverty level, exceeding the household count of any zip code in the state, according to U.S. Census estimates. The second highest is 33142, Miami's impoverished Brownsville at about 7,200 households.

For the children in those homes, staying healthy is a profound challenge. Affordability and access to dental care, medical treatments and nutritious foods are lacking.

Aggravating the problem is a dearth of specific local data on health factors that veils the scope and complexity of problems children in 32304 face every day.

“If you don’t gather the data, you don’t know,” said Dr. Joedrecka Brown Speights, a Florida State University College of Medicine professor and expert on family, maternal and child health. “Data really drives optimal responses. It allows you to become more strategic.”

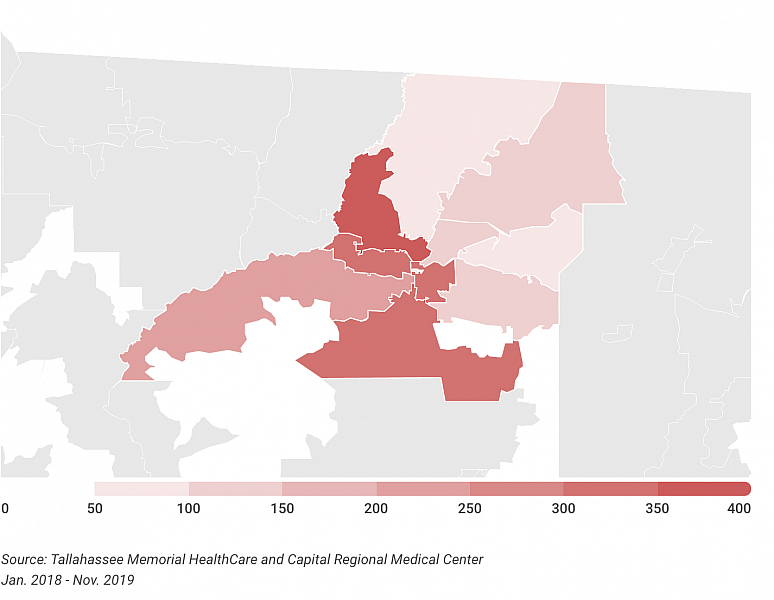

Children's ER visits - Asthma

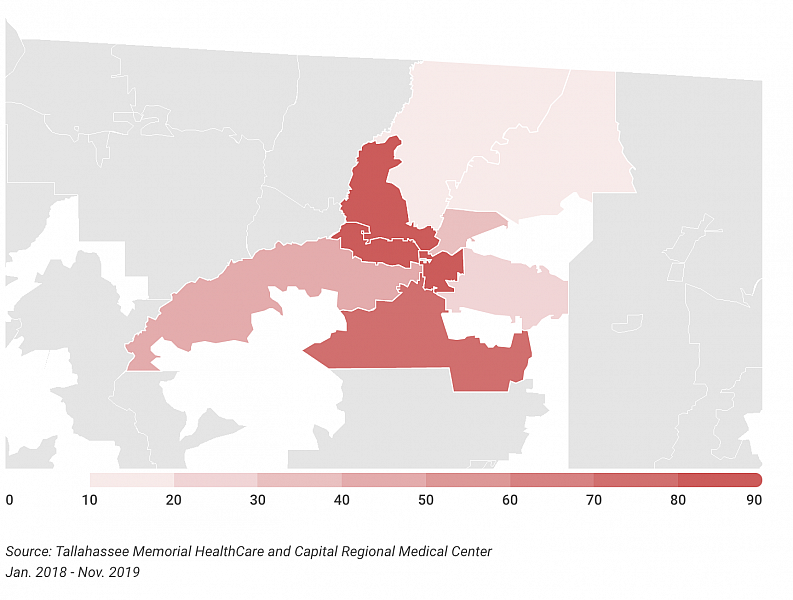

Some available information, however, provides clues. Like those in other high-poverty zip codes in Tallahassee, children in the area visit the emergency room for dental issues and asthma significantly more than kids in more affluent zip codes, according to data obtained by the Tallahassee Democrat from the city’s two main hospitals.

Public health experts know ER visits and those exact ailments are hallmark symptoms of disparities in health-care access.

The coronavirus outbreak has further exposed those inequities as it upends already tenuous lives. The 32304 zip code has the highest number of coronavirus cases among all zip codes in Leon County — 190 of 642 cases as of Thursday morning. The next highest is neighboring 32303 with half that number.

Children's ER visits - Oral Health

About a sixth of 32304’s cases are tied to residents of the Tallahassee Developmental Center, a facility for adults with disabilities where about three dozen residents tested positive for the virus.

Early findings show COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus, strikes communities like 32304 harder than others because of pre-existing conditions related to poverty. Those who were vulnerable before are even more vulnerable now.

“This is compounding the problem,” said Miaisha Mitchell, a local advocate for families in 32304 and a former health care administrator of three decades. “Folks who have been disproportionately impacted are further down on that ladder.”

'I can't afford that'

On the northeast edge of 32304, three miles away from the state Legislature are the Springfield Apartments, a series of pale orange buildings on Joe Louis Street that comprise one of the city Housing Authority’s largest public housing complexes.

Surrounding the projects are some of the most dangerous, tattered blocks in town. Along state-named streets like Indiana and Alabama, many of the tumbledown homes are mold-stained, with missing panels and broken carports. Kids walk back to bare porches from Riley Elementary, nestled across the street.

Simms moved to Springfield Apartments after she and her two daughters spent a year homeless. She couldn’t afford to pay rent when she separated from her husband. They shared a house with a friend in West Palm Beach, then spent another six months couch surfing with relatives.

Before slicing meat and subs at the Mahan Village Publix and delivering groceries with Instacart, the 38-year-old cleaned hotel rooms and oversaw housekeeping staff at the Fairfield Inn.

With an annual income of $23,000, she can’t afford the insurance plan offered by Publix insurance – $30 out of her paycheck.

“How do you expect a single mom to pay $50?” she said of the plan’s co-payments. “I can’t afford that.”

And coming up with gas money to get her then-17-year-old daughter Naya to dental appointments is a struggle.

“It was either Panama or Gainesville. Anything that’s outside of certain brackets you have to drive so far, and I just think that’s so crazy,” Simms said, sitting on her living room sofa still dressed in her orange Publix uniform. “It’s a couple surgeons right here, why are they not accepting Medicaid?”

A dental hygienist cleans 11-year-old Deitra "DeeDee" Jackson’s teeth at Neighborhood Medical Center. ALICIA DEVINE/TALLAHASSEE DEMOCRAT

Both Naya and her 11-year-old sister DeeDee have Children’s Medical Services insurance, a state program for kids with complex health issues. The sisters both have ADD – attention deficit disorder – and DeeDee also suffers from asthma.

On a late November day, DeeDee snacked on a sausage pancake and a hot sausage. She and her mom playfully fought over the last watermelon popsicle and argued about what to make for dinner: shepherd's pie or chili?

The sisters don’t take their medications on the weekends. It saves them pills and “gives them a break,” Simms said.

The other day, the Joe Louis Street mom got $28 in child support from her daughter’s dad. That day, she and her girls had breakfast.

Simms said she must fight for doctor appointments for the girls. For teeth cleanings, she takes them to the federally designated low-income health clinic, Neighborhood Medical Center. None of its locations, nor the town’s other low-income clinic, Bond Community Health, are in 32304.

She feels her community is often slighted, overlooked.

“They won’t help people here because, I wouldn’t say racist, but you’re being labeled just because for the resources you need,” Simms said. “You basically gotta search and dig, or y’know, fight over here, versus in another area in Tallahassee you’re going to get the assistance.”

A Joe Louis Street single mom Kisha Simms spends an afternoon at home with her girls, and takes the younger one DeeDee, 11, to the dentist. ALICIA DEVINE/TALLAHASSEE DEMOCRA A Joe Louis Street single mom Kisha Simms spends an afternoon at home with her girls, and takes the younger one DeeDee, 11, to the dentist. ALICIA DEVINE/TALLAHASSEE DEMOCRA

As the coronavirus outbreak continues and experts warn of a second wave in the fall, Simms wonders how long she and other parents will have to keep driving 200 or 300 miles round-trip for their kids’ doctor’s appointments.

Simms, who hasn’t yet received her stimulus check, has lost hope in officials. She's stopped waiting on them.

“It just makes me motivated to do what I need to do,” she said. “Motivated to make me save, and make sure I’m focused. And go out and speak to our people so we can help them.”

'What am I supposed to do?'

In the barren patch in front of Myssty Ochoa’s Aenon Church trailer, 8-year-old Romeo and his 3-year-old sister Victoria draw on the porch the family cobbled together out of plastic curtains and a bench. They used a power-line spool leftover from Hurricane Michael as a patio table. It’s a refuge in their downtrodden neighborhood.

Victoria, 3, and Romeo 8, play inside their Aenon Church mobile home as their mom Myssty Ochoa looks on. ALICIA DEVINE/TALLAHASSEE DEMOCRAT Victoria, 3, and Romeo 8, play inside their Aenon Church mobile home as their mom Myssty Ochoa looks on. ALICIA DEVINE/TALLAHASSEE DEMOCRAT

When he first learned to walk, Ochoa says, doctors told her Romeo eventually would grow out of tip-toeing. One doctor suggested she buy him a bicycle to stretch his tendons out.

“But they never did stretch out. And so now, he can’t extend his leg all the way out. Because the muscles have grown how he’s stood,” said the 28-year-old mom.

Dr. Brown Speights has studied the long-term impacts on children and families like Ochoa’s, who’ve lacked access to the care they need.

“What we know about kids is early detection and intervention are very important. Kids are malleable,” said Dr. Brown Speights. “They’re little people growing … late intervention, not getting any care at all, it just kind of puts people behind in life. And it doesn’t allow kids to have the fullest life.”

Romeo can’t play soccer or football like his next-door neighbor and other kids his age, Ochoa said.

Ochoa quit her job at Hobbit American Grill making a penny above minimum wage, earning just enough to pay a babysitter, but not much else. She also takes care of her 12-year-old sister. Ochoa’s husband, who frames houses, built the girl a room into a corner of the 600-foot trailer.

Victoria, 3, jumps on her mom's bed while her 8-year-old brother Romeo plays Xbox games. The siblings live with their mom, her younger sister, and their mom's husband. ALICIA DEVINE/TALLAHASSEE DEMOCRAT

With three children and one paycheck, coming up with money to make ends meet and pay for Romeo’s X-rays has been a feat.

“I had to pay the rest of it up front. And I couldn’t,” said Ochoa, wiping tears from her eyes. “So, I mean, what am I supposed to do?”

It can be a maze to navigate what’s covered and what’s not. Doctors themselves have trouble advocating for patients’ coverage.

Dr. Mary Norton runs into this problem daily. A pediatrician at the FSU PrimaryHealth clinic, her patients are mostly on Medicaid and come from underserved populations.

It often takes weeks for Medicaid to approve prescriptions, lab work or imaging – or reject them.

“I’ve had difficulties getting nebulizers for kiddos that have had severe wheezing episodes and have had to go to the emergency room,” Norton said. “You need treatments for wheezing every 4 to 6 hours. Waiting days or weeks for a nebulizer is not acceptable.”

Most of her patients who need nebulizers to deliver oxygen and medicine to their lungs and help them breathe are young, 4 years old and under.

Despite Norton’s staff stipulating the need to Medicaid, blood tests to diagnose diabetes or cholesterol problems in children with obesity often receive pushback too.

The parent ends up having to shell out the cash, despite being covered.

Brown Speights says situations like Ochoa’s, where there’s partial access to coverage but a lack of resources to fill in the gaps, are perfect examples of overlooked disparities in care.

“Inequities happen when you don’t provide resources according to need,” she said. “Someone could have access, but still not have access. You don’t have full-on what you need to be completely healthy … (like) getting an X-ray so you can get diagnosed with a bone issue.”

The long-term effects include not just an unresolved health issue but the family’s resulting mistrust of the system.

“Now, you’re dealing with a family or a child where the system hasn’t worked well for them,” she said. “And it’s not going to be inviting next time they have to go through that system.”

'There's nothing out here for people'

Between U.S. 90 and 20, off Aenon Church Road are clusters of run-down, distressed trailers with rusted walls and rotted wooden porches. At night, few streetlights come on. But the darkness doesn’t hide the squalor.

Thirty-six-year-old Michelle Kirkland and her family live here. With irregular work hours and a tight budget, venturing to the other side of town for her kids’ doctor’s appointments is hard — as is finding and affording nutritious food.

On a fall day, her kids, 9-year-old Vivianna and Brandon Hughes, 11, come home from school and rush to the kitchen for an afternoon snack.

Sometimes it’s Publix fruit-on-the-bottom yogurt. That day, it was tuna, raisins and a jar of marshmallow fluff studded with crisped rice cereal. The siblings burst into boisterous laughter and Vivianna munches while solving math problems.

Kirkland once tried to plant an edible garden filled with vegetables. Her kids on the other hand are pickier, so her pantry is stocked with plenty of Hamburger Helper. It’s the weeknight go-to.

Tiny roaches crawl along the walls and the kids don’t bat an eye. They’ve made a game of smacking them. Their Christmas wish for a cheaper, pest-free trailer came true. They moved into one off U.S. 20 by Munson Slough’s swampy bend.

But soon after, the COVID-19 crisis slashed their income. They’d gathered toilet paper and hand sanitizer from the dollar store down the road on Blountstown Highway. A Walmart is the only grocery store for at least 5 miles.

As the coronavirus shut schools down, she relied on her food stamps to feed her kids lunch.

“We have been poor enough to get the kids free lunch, always,” Kirkland said. “I am poor enough for my kids to get Medicaid and get food stamps, but not to get Medicaid myself.”

When she was pregnant with Brandon and Vivianna, she’d head to Bond Community Clinic’s former location near FAMU for check-ups. It was about 9 miles from her current Aenon Church neighborhood, and 13 miles from where she lived at the time.

“There is no access. It’s all the way on the other side of town. I mean, there’s nothing nearby,” Kirkland said. “That’s just how hospitals go and health centers. Most of them are all the way on the other side of town.”

Dr. Temple Robinson, who runs the low-income Bond Community Health, sees families like Kirkland’s and knows the barriers they face for care.

“If you have to pay for a ride to go to a doctor’s appointment and the child is well, you’re less likely to do that,” said Robinson, who helped start the Bragg Stadium walk-up testing site to help bring coronavirus tests to south side residents.

“If you’ve got to take three buses to go get a shot for a child that’s well and your time is so tight that there are other things you need to do, or this is the day you need access to other social services, how do you make the rounds?”

Preventative health care is often placed on the back burner. Access is the No. 1 disparity Robinson sees in her low-income pediatric patients, causing missed appointments.

Until Kirkland bought a car recently, the family of four walked to the store for groceries. Before she lost her job to the pandemic, her erratic work schedule hindered taking her kids to the doctor for check-ups. Sometimes, her shifts counting retail inventory wouldn’t end until 2 a.m.

“There’s nothing out here for people,” her husband Brandon Hughes said, throwing his hands up. “The school is what, 15 miles out? Come on, man. What are we supposed to do? The buses stop a mile and half from here.”

That’s why he bought a bicycle. An hour to get to the bus stop was ridiculous, he said.

“Once you cross Capital Circle, coming into the outskirts of Tallahassee, there is nothing,” he said. “It’s like Tallahassee ceases to exist.”

About This Project

The news that the 32304 zip code has the most households in poverty in the state prompted the Tallahassee Democrat to ask: What is life like for children there? How does poverty impact their health? Reporter Nada Hassanein sought to answer that in a six months-long reporting process to find answers, get to know families and mine for data.

The photography for this series was captured by photojournalist Alicia Devine. The photo editor was Mark Wallheiser. Jennifer Portman, USA Today enterprise editor, was the project editor.

This series was supported by the University of Southern California Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2019 National Fellowship and the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

[This article was originally published by the Tallahasee Democrat.]