Pregnant during pandemic: COVID-19 fears fuel increased interest in home births

This is the fourth in "Pregnant During Pandemic," a series by Olga Grigoryants, a participant in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 California Fellowship.

Her other stories include:

Part 1: Pregnant during pandemic: Programs, midwives step up to support Black mothers

Part 2: Pregnant during Pandemic: Black midwives in demand; are there enough to handle influx of clients?

Part 3: Birth centers grow in popularity, but owners say it’s difficult to qualify for state license

Part 5: Pregnant during pandemic: Expectant mothers remain at high risk of COVID-19

Tameka Issartel and her daughter Nalani, 5, laugh with Tenshin, 7 months, in their El Sereno living room on Thursday, September 9, 2021 where Issartel birthed Tenshin. Midwife Racha Tahani Lawler pulled off her N95 and performed CPR all the way to the hospital after Tenshin struggled to take his first breath.

(Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG)

When Tameka Issartel went into labor shortly after midnight on Feb. 3, she found herself drifting into a trance-like state. She didn’t remember when her husband called their midwife or how she arrived with her assistant at her El Sereno home.

Midwife Racha Tahani Lawler describes Tameka Issartel’s difficult labor where she had to perform CPR on the baby all the way to the hospital after he had trouble taking his first breath during a coronavirus surge. (Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG)

As her pain intensified, Issartel spent several hours moving around her house, stepping into a shower, sitting in a bathtub and leaning up against the sofa in her living room, while midwife Racha Tahani Lawler massaged her back and encouraged her through labor. But the baby was still not coming out.

The pain grew so intense, Issartel said, she roared like a tiger.

That’s when the midwife told her husband to call 911.

Issartel kept pushing, changing her birthing positions several times with the assistance of midwives and her husband, who was also trying to take care of the couple’s three daughters patiently waiting nearby to meet the baby.

When Issartel’s son finally arrived around 9 a.m., she noticed that he was not breathing. Her daughters surrounded the baby as Lawler kneeled next to him, pulled off her N-95 mask and performed CPR, as Issartel stared in shock.

“Breathe, baby, breathe,” one of the girls said. “Come on, Tenshin.”

Rising interest in home births

Home births have been on the rise across the Los Angeles region for the last couple of years, in part because of the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic.

More women have been opting for home birth as hospitals postponed or moved most of their health care online due to the pandemic, barring partners, canceling antenatal classes and often leaving women to deliver and recover alone. And many women chose home delivery because they were worried about being exposed to the virus at hospitals.

Another factor contributing to the rise of home birth, experts say, is the growing awareness of health disparities in maternal and infant mortality faced by Black women, who bear a greater risk of childbirth complications than any other demographic group, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

It’s estimated that about 700 women die each year in the United States from pregnancy-related complications, including infections, severe bleeding and high blood pressure. Black, American Indian and Alaska Native women have been disproportionately affected by pregnancy- and birth-related complications, with the CDC reporting they are two to three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than other demographic groups.

Interviews with more than two dozen midwives indicate they have attended double or triple the number of home births since the first days of the pandemic, with many of them unable to meet the demand and even turning clients away.

Lawler said she has been receiving dozens of inquiries each day from families inquiring about home birth. On some days, she visits her clients not to provide any prenatal or postpartum care, but just to hold their babies and listen.

“So many Black people are struggling with feeling whole because of everything that is going on,” she said. “They are piecing themselves together, worrying about the pandemic, worrying about their family, worrying about their housing, worrying about their food and struggling to hold it together.”

Nurse midwife Shadman Habibi, who works at UCLA Health Birth Place in Santa Monica, said at least 25 women of 150 patients who were planning their deliveries there changed their birthing plans in the past few months.

“They stopped coming to us and decided to have a home birth,” Habibi said.

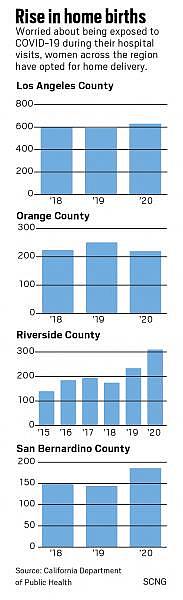

The number of home births in Los Angeles County increased by 5.3% to a total of 631 from 2018 to 2020. During the same period, the numbers in San Bernardino County increased by nearly 25% to 186, according to preliminary data from the California Department of Public Health.

In Riverside County, that number rose by 121% to 310 from 2015 to 2020, according to the Riverside University Health System-Public Health.

In Orange County, the numbers have remained about the same from 2018 to 2020, according to the California Department of Public Health.

Licensed midwife Angelica Miller, who is based in Long Beach, said she has seen an uptick of inquiries about home birth since last year.

“A lot of moms choose home birth outside the pandemic because they can be active participants of their care,” she said. “With the pandemic, it’s a fear of COVID.”

Many of her clients, Miller added, choose a home delivery because they want to have control over their birth experience and make sure their needs are met.

One of her recent clients, MyLin Stokes Kennedy, decided to have an out-of-hospital birth after witnessing her wife, Lindsay, being pregnant with their son Lennox about two years ago. She watched in shock as an obstetrician failed to check on her wife while she was in pain.

Stokes Kennedy made up her mind to deliver her baby at home once she became pregnant with the couple’s third child.

“I’m just more aware of what’s happening to women like me in the hospital,” said the 34-year old resident of Fountain Valley, who is Black. “I didn’t want to be part of those statistics.”

Stokes Kennedy said she was drawn to home birth and midwifery care because of its focus on avoiding unnecessary interventions. The idea of receiving guidance and support from a midwife made her feel seen and heard. The pandemic was the final straw, she added, convincing her to opt for out-of-hospital delivery.

Lindsay Stokes Kennedy wrote her wife MyLin’s birth affirmations on a mirror where Mylin’s paintings are reflected as seen on Thursday, September 16, 2021. (Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG)

“With the pandemic, I wouldn’t want to be in the hospital,” she said.

It took her more than two months to find Miller, a Black midwife who attended home births in Orange County.

She envisioned delivering her baby in a birthing tub surrounded by candles, lavender scents and family members.

“I wanted a holistic, beautiful, spiritual journey and it has been like that so far,” Stokes Kennedy said. Miller, she added, encouraged her to ask questions during appointments that sometimes stretched to more than an hour — a type of care she believed she wouldn’t get with obstetricians.

But once she went into labor in the late hours on Sept. 3, all her birthing plans went out of the window.

As her labor progressed quickly, her contractions became longer and more intense. She labored in the bathroom for a while before her water bag dropped. About 30 minutes later, with the midwife still on the way, Stokes Kennedy noticed the baby’s head popping out.

“I said: ‘My baby is coming,’ ” she said.

When Lindsay heard her wife’s voice, she ran over from the dining room, where she was filling the birthing tub with water, and encouraged her wife to breathe and keep pushing. Stokes Kennedy’s doula, mother, and 13-year-old son stood by her side.

She pushed and pushed. Then she rested for a minute and pushed again.

Maddox Levi was born before midnight on Sept. 3. He weighed 9 pounds, 3 ounces and was 23 inches long. Right after he was born, the family FaceTimed the midwife and stayed on the call until she arrived about 15 minutes later.

Stokes Kennedy said although her mother was nervous witnessing home birth without professional help, no one considered calling 911.

“I was safe at home,” she said. “It was never a terrible pain. … Once his head was out, he was fine. There was never any worry.”

Although Stokes Kennedy didn’t have a chance to experience a water birth or light $200 worth of candles, she said she would do a home birth again. “My wife caught the baby,” she said. “It was very calm, intentional and beautiful.”

MyLin Stokes Kennedy rests at home on Thursday, September 16, 2021 with her son Lennox and Maddox, who her wife Lindsay delivered in their Fountain Valley home days ago. (Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG)

As the pandemic continued battering hospitals, midwives say they occasionally received phone calls from women who couldn’t afford to pay for midwifery care but needed advice preparing for an unassisted birth, also known as free birth.

Some expectant mothers turned to Facebook groups, seeking advice on unassisted birth where women shared pictures of themselves laboring in inflatable pools surrounded by candlelight and family members. They also asked questions on how to talk to neighbors about potential screaming during labor, whether free birth is possible with previous C-sections and if there’s a need to call 911 if labor doesn’t progress after a certain period of time.

Although free birth is not illegal in California, there have been instances in other states in which women who delivered stillborn babies at home have been prosecuted.

Doctors maintain that hospitals remain the safest option for pregnant women even amid the pandemic.

Dr. Amos Grunebaum, an obstetrician and gynecologist and a professor at the Zucker School of Medicine in New York, said out-of-hospital birth puts mothers and babies at risk.

“Complications can happen quickly and unexpectedly, even with people who have low-risk pregnancies,” he said. “People who deliver at home put their babies at an increased risk.”

Grunebaum and a team of researchers examined records from 2016-2018 and discovered that nearly 60% of women who planned a home birth had risk factors that could potentially end up in complications and neonatal mortality, according to a study published in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and covered by Reuters.

“These significantly increased risks of neonatal mortality in home births must be disclosed by all obstetric practitioners to all pregnant women who express an interest in such births,” according to the study.

Grunebaum was among a group of researchers who analyzed National Center for Health Statistics data on 88,000 planned home births across the county and discovered that nearly 4% of births followed prior C-section, about 23% of the mothers were 35 or older, and nearly 5% were 40 or older.

He also found that expectant mothers chose home birth despite risk factors like older age, prior cesarean delivery or obesity — factors which whole disqualified them from home birth in other developed countries.

“You have only one or two babies in your life,” he said. “Why would you risk it?

Dr. Mya Zapata, an obstetrician and gynecologist and the chief of the obstetrics service at Ronald Reagan Medical Center at UCLA, said she would recommend having a baby in the hospital.

“Most patients who get COVID, get it in the community from people they interact with,” she said. “The risk is much higher of getting COVID going to other locations and gatherings. In the hospital, at least the health care workers are vaccinated and everyone is wearing a mask.”

No regrets

As the Issartel family was waiting for paramedics to arrive, Lawler continued performing CPR for at least 12 minutes.

During labor, Issartel learned that the baby was large and his shoulder was stuck inside her pelvis, a birth complication known as shoulder dystocia.

When paramedics arrived, they put Lawler on the gurney with the baby as she continued performing CPR.

“I was terrified that I was going break his ribs,” she said.

Issartel, 34, was transported to the hospital in a separate ambulance.

At the hospital, the boy received a cooling treatment, also known as therapeutic hypothermia, used to treat babies who were deprived of oxygen during birth. The treatment lowers the baby’s body temperature to prevent his or her health from deteriorating, by stopping the death of oxygen-deprived cells.

Tameka Issartel poses with her husband Yukio Hoshi and their children Kalea, 10, Tenshin, 7 months, Nalani, 5, and Luana, 7, in their El Sereno living room on Thursday, September 9, 2021 where she birthed Tenshin. Midwife Racha Tahani Lawler pulled off her N95 and performed CPR all the way to the hospital after Tenshin struggled to take his first breath. (Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG)

Because of pandemic-related restrictions, Issartel was not allowed to see her son until later in the afternoon. She was allowed to hold him for the first time only after three anxious days.

When doctors returned the boy’s temperature back to normal three days later, Issartel placed him on her chest, watching him latch onto her breast right away, with breathing tubes and oxygen still attached to his body. His MRI images showed no signs of trauma or injury.

“I was very blessed that we didn’t have any issues with nursing,” she said.

Before Tenshin was born, Issartel said she was debating whether to have a home birth. She even considered unassisted birth, but eventually decided to hire a midwife.

“I didn’t want to go to the hospital in the middle of the pandemic,” Issartel said.

Home birth allowed her and her son to avoid lengthy and painful recovery, which Issartel said took more than two months after her previous pregnancy.

“I do believe this is really meant to be,” she said. “If I was in the hospital, the healing journey for him and I would be worse. I have no regrets.”

Olga Grigoryants’ reporting on pregnancy during the pandemic was undertaken as a project for the USC Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 California Fellowship.

[This article was originally published by Los Angeles Daily News.]