Project Roomkey funding ends soon. Over 11,000 Californians could become homeless, again

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Nicole Hayden, a participant in the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2020 California Fellowship.

Her other stories in this project include:

Riverside County advocates want COVID-19 testing for homeless on the streets

Palm Springs shelter avoided COVID-19. Homeless say they need more than protection from virus

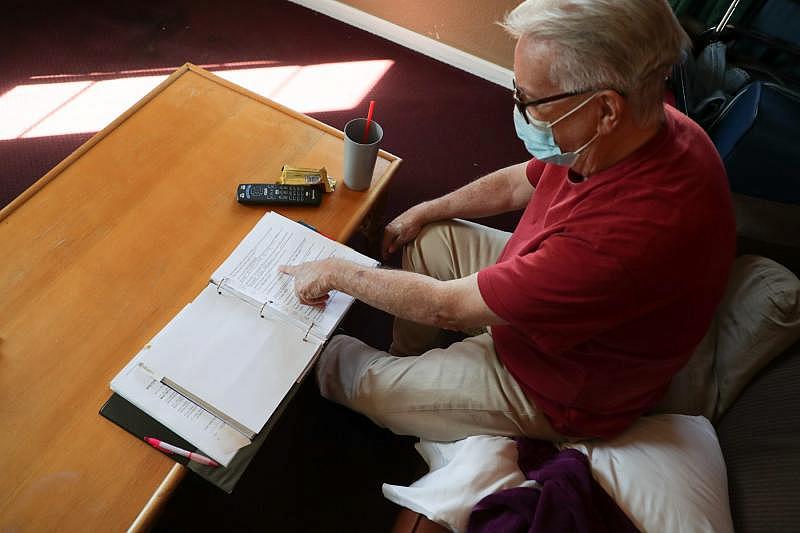

Lee Fournier sits in his hotel room provided by Project Roomkey on Sunday, October 11, 2020, at Rodeway Inn & Suites in Indio, Calif. Project Roomkey is an effort by the state to house individuals experiencing homelessness during the COVID-19 pandemic.

VICKIE CONNOR/THE DESERT SUN

A 2-inch-thick binder labeled "housing choice voucher program" sits on the coffee table of Lee Fournier's hotel room in Indio.

The 73-year-old man compiled it on his own, piece by piece. Pertinent business cards are slipped into the clear insert with the names of housing caseworkers whom he talks to on a regular basis. Inside, papers are organized by tabs.

On a recent day in October, Fournier hoisted himself forward on the sinking sofa that gives him trouble due to his bad back. He leaned forward slowly and his hands, stiff from age, flipped to a section in the binder titled “listings." Written in his looping handwriting, it included information about 14 potential affordable housing units.

He has called the landlord for each, repeatedly, since he was approved for a voucher on Aug. 12. So far, none have worked out.

"I lost out on some of the applications because I couldn't afford the fees," Fournier said.

Most applications required money upfront for a background check or to hold the unit. While Fournier submitted paperwork for all 14, some of the accompanying fees neared $200. His $1,700 monthly Social Security check is already stretched thin.

The pressure to find housing is mounting for Fournier, whose room at The Rodeway Inn could be revoked at the end of the year. On a piece of paper at the front of his binder, “notice of termination from program” is typed along the top. It's accompanied by a logo for Project Roomkey, reminding him that the state program that paid for his hotel room is winding down.

Gov. Gavin Newsom launched Project Roomkey in April, aimed at securing thousands of hotel rooms across California to shelter homeless individuals to prevent them from contracting COVID-19. The program targeted seniors, pregnant women and others at risk for being particularly vulnerable to having severe COVID-19 symptoms. More than 28,000 people — 17% of the state's homeless population —have received shelter under the $150 million program, which was rolled out in most of the state's 58 counties.

Fournier received a placement within Riverside County, one of 38 counties still operating the program.

But Project Roomkey was never meant to be a permanent solution. Many counties have already shut down their programs, kicking clients out of rooms due to lack of funding or refusing to take more in. Come Dec. 30, statewide funding will end, forcing many others to shutter their programs completely or line up new monies to allow people to stay longer.

"If I end up homeless again, I don't know where I'd go," said Fournier, who has been homeless for just under a year as he couldn't find affordable housing after his former lease ended. Prior to retirement, he worked in medical billing near Los Angeles.

"I guess I have my car to stay in," he said.

Statewide, only 5% of Roomkey clients have found a permanent home, according to an analysis by The Desert Sun.

//

The Desert Sun analyzed Project Roomkey by requesting client and placement data as of mid-October from all 58 California counties. Of the 45 counties that responded, 36 said they participated in the program. Thirteen counties did not respond.

Those 36 counties have served 28,716 Roomkey clients since April. Of those, 16% returned to homelessness, 40% are still in a hotel room but could face eviction come the new year, and 39% left the program but caseworkers don't know where they went.

To be sure, since at least 11,620 Project Roomkey clients are still housed in hotel units across the state, total data is not yet complete.

What local officials do know is that while Project Roomkey succeeded in initially sheltering thousands of homeless individuals to curb the spread of COVID-19, funding was quickly depleted. Counties are now scrambling to find long-term housing solutions.

A subsequent state initiative called Project Homekey aims to rehabilitate old hotels and motels into affordable apartments, but not all counties received funding. And for those that did, some of the projects won't be ready for move-in before the end of the year.

That means nearly 12,000 people, mostly clustered in California’s largest counties, face the possibility of returning to homelessness amid the pandemic, once again.

Lee Fournier sorts through a binder with potential housing options in his hotel room provided by Project Roomkey on Sunday, October 11, 2020, at Rodeway Inn & Suites in Indio, Calif. Project Roomkey is an effort by the state to house individuals experiencing homelessness during the COVID-19 pandemic. VICKIE CONNOR/THE DESERT SUN

How did the state fund Project Roomkey?

Newsom announced the launch of Project Roomkey on April 3, with an initial goal of securing up to 15,000 hotel rooms across the state. Counties clamored to set up hotel contracts in the following month.

The program cost anywhere from $57 to $300 per night per hotel room, depending on the level of service provided to individuals, according to data collected by The Desert Sun. The state released $150 million in limited emergency funding and negotiated a reimbursement agreement with the Federal Emergency Management Agency to help counties accomplish the feat.

But not everyone received that funding. Some counties opted to tap into their own annual homelessness funds, while others couldn't shoulder the cost.

Newsom assured counties they needn't worry because the FEMA reimbursement could refund 75% of costs incurred by the programs. Costs that could be reimbursed included hotel rooms, meals, and security and custodial services. Any additional services, such as behavioral health, health care services and case management, would need to be directly funded by counties themselves.

Rodeway Inn & Suites in Indio, Calif., partnered with the state for Project Roomkey, an effort by the state to house individuals experiencing homelessness during the COVID-19 pandemic. VICKIE CONNOR/THE DESERT SUN

Some, such as Lake County, were hesitant to solely rely on FEMA reimbursements as the federal agency has been slow to pay in the past. Lake County chose not to continue its Project Roomkey program after using up the state's initial $100,000 allocation to serve 12 clients because it didn’t have the capacity to produce funding upfront.

“Lake County is a small, rural, impoverished county that has been hit hard by wildfires and floods annually since 2015,” said Crystal Markytan, the county's public administrator. “Lake County is still recovering FEMA dollars from the 2015 Valley Fire, with many other disasters in the intervening years, waiting in line.”

Of the counties surveyed by The Desert Sun, nearly 100% said more state and federal funding is needed to provide long-term housing solutions as most counties solely rely on state and federal funding. Riverside County, for example, funds just 1% of homeless services from its own budget.

“While grateful for increased funding for homelessness from the state and federal government, …most has been one-time funding,” said Janna Haynes, Sacramento County spokeswoman. “Not knowing for certain if future funding will be available to continue to fund programs makes it difficult to plan for long-term solutions.”

'We didn't build an exit strategy'

Some California counties always viewed Project Roomkey as a short-term band-aid, meant just to provide temporary shelter for individuals experiencing homelessness to stop the spread of COVID-19 through encampments and mass shelters.

And in some ways, it helped. While the California Department of Public Health said it did not have statewide data on the number of COVID-19 cases among homeless individuals. Riverside County reported homeless individuals accounted for 0.6% of its cases — though that still equates to 402 people, or 14% of the county's estimated homeless population.

Counties such as Fresno, Sacramento and Santa Cruz didn't provide case management as part of their Project Roomkey programs, which can include mental health services and housing assistance.

“When we started our own program, we thought by June 30, we would be done,” said Laura Moreno, Fresno County social services program manager. “We didn’t implement any (long-term) stuff because it was an emergency, and we just wanted to get people inside. We never expected to still be here in October.

"Sheltering in place was so critical at that point," she added. "People wanted to wander so we'd say, 'No stay here, we will give you a pack of cigarettes.'"

Fresno County launched its program using state and federal funds. Even if officials wanted to add caseworkers and set people up to secure permanent housing, Moreno said the initial state monies didn’t support costs for staff, or to pay for the technology used to track clients' housing progress.

Of the total number of homeless individuals served by Fresno County, 36% have returned to homelessness. About 27% have transitioned to permanent housing. Both numbers are higher than the state average.

“(People returning to homelessness) is not surprising given that many of these people came inside to a shelter for the first time (during the pandemic),” Moreno said. “Many people who came to these shelters were not previously known to our system.”

Fresno County now has more homeless individuals in emergency shelter than ever before — nearly 400 people — and funding to keep them there is about to end.

“We didn’t build an exit strategy,” Moreno said. “Now we are working backwards."

Fresno County has begun performing assessments of hotel clients to determine what kind of subsidized housing they might qualify for. Additionally, the county's Homekey project will create 165 affordable apartments ready for move-in by the end of the year.

"Right now we have no way to find 400 (permanent housing) units to put these folks in," said Moreno. "That’s why Project Homekey will be a lifesaver for us.”

Rodeway Inn & Suites in Indio, Calif. partnered with the state for Project Roomkey, an effort by the state to house individuals experiencing homelessness during the COVID-19 pandemic. VICKIE CONNOR/THE DESERT SUN

One caseworker for every 36 Roomkey clients

Other counties viewed Project Roomkey from the start as a launching point to help transition individuals into their own apartment by providing social workers to anyone who received a hotel room. But those counties grappled with a challenge that they've faced for years: funding for enough staff.

Emmanuel Baxa, a social services worker who typically works in adult protective services, was reassigned to Project Roomkey to help bolster the program when it launched in Riverside County. At its height, Baxa juggled 20 clients at once — more than he’s ever been assigned in the past, he said.

Nineteen caseworkers were assigned to more than 800 Project Roomkey clients over the span of the program, county officials said. Clients stayed an average of 104 nights.

That ratio was mirrored across California: Of the 29 counties that provided relevant data, the average ratio was one caseworker for every 36 Roomkey clients, according to a statewide data analysis by The Desert Sun.

“If I had it my way, I think 15 clients would be a manageable number in a perfect world,” Baxa said. “But with today’s issues and pandemic crisis, we are currently not in a place where that will ever happen.”

Still, Riverside County had moderate success among the counties that have seen a higher percentage of clients housed: Its homeless population falls within the top 10 in the state, and it had the ninth-highest success rate with 15% of Roomkey households moving from hotel rooms to housing.

“Our goal is to not just offer shelter during the emergency period but to offer a true pathway back to permanent housing and financial stability for these clients,” county spokesman Jose Arballo said.

Baxa tries to visit with each of his clients at least once a week. Fournier said Baxa helped him sign up for an EBT card and navigate the process of calling available apartments within his personal budget.

Other clients take more extensive follow-up, Baxa said. One of his clients recently needed assistance to address hoarding behaviors that could have led to his landlord kicking him out. Another client continued to misplace multiple cell phones, so Baxa helped him install a landline at his apartment.

More time with clients can lead to more successful housing placements, Baxa said.

“With perseverance, we are able to convince and secure housing for even the most challenging cases,” Baxa said.

Lee Fournier sits in his hotel room provided by Project Roomkey on Sunday, October 11, 2020, at Rodeway Inn & Suites in Indio, Calif. Project Roomkey is an effort by the state to house individuals experiencing homelessness during the COVID-19 pandemic. VICKIE CONNOR/THE DESERT SUN

Counties search for funding, affordable housing

Still, 43% of Roomkey clients in Riverside County — about 375 people — remain in one of many hotel units scattered across the state's fourth-most populous region. Already, 29% have returned to homelessness, an emergency shelter or haven’t been able to be tracked.

Knowing that funding would soon be depleted, Riverside County stopped accepting new clients for hotel rooms in September and is now making transitional plans for the end of the year.

Officials say they will not kick clients out on Dec. 30. Instead, county staff is working to find additional emergency funding that will allow clients to remain in the hotels. This new program will be "much smaller" and caseworkers were told to notify clients that they should start looking for "more stable" shelter options, county officials said.

"The smaller program is contingent on state funding," said Arballo, the county spokesman. "We do not have an exact figure for how many beds will be available through this replacement program. It could range from 100 to 200.”

The county is hoping individuals that have already received housing vouchers will be able to secure an apartment by then. Of the nearly 375 individuals still in hotel units, 31% have already been approved for a housing voucher — this includes Fournier.

However, the lack of housing stock continues to be a challenge, said Marcus Dillard, Riverside County Housing Authority supervisor. As a result, many individuals are stuck in a hotel room in limbo and may not secure housing before the year's end, he said.

Riverside County currently has less than 30,000 affordable housing units and needs more than 66,000 new units to meet current needs, Arballo said.

Newsom's solution for this housing gap came in the form of Project Homekey.

More than half of the counties that received funding and responded to The Desert Sun reported that they expect their converted affordable housing projects to be available at the end of the year, right when Roomkey funding runs out to allow people to move from their temporary hotel unit to a permanent home.

However, some of the counties don’t expect their Homekey projects to be ready for habitation until mid-2021 or even later. Riverside County's biggest project to house anyone, including those currently in hotel rooms, will not open its doors until May 2023.

Riverside County has two additional Homekey projects that will come online sooner but are tailored to specific populations, farmworkers and LGBTQ youth.

A majority of California counties did not receive Homekey funding — 61% won't have this long-term solution to provide, according to a Desert Sun analysis.

Lee Fournier's hotel bedroom provided by Project Roomkey is photographed on Sunday, October 11, 2020, at Rodeway Inn & Suites in Indio, Calif. Project Roomkey is an effort by the state to house individuals experiencing homelessness during the COVID-19 pandemic. VICKIE CONNOR/THE DESERT SUN

Which counties saw success? Which did not?

Counties with the greatest success out of Roomkey had the smallest populations to house, according to The Desert Sun's analysis.

Those counties included Tuolumne County, which saw 58% of its Roomkey clients transition to housing, as well as Santa Barbara with 35%, Mariposa with 30%, Del Norte with 22% and Riverside with 21%.

Yet other small counties topped the charts for clients returning to homelessness. Glenn County saw all six of its Roomkey clients back on the streets when the program shut down; Humboldt County saw 61% of its clients return to homelessness; followed by Tulare at 60%, Yolo at 58%, and Monterey at 59%.

Some of the biggest counties with the largest number of homeless individuals — like San Diego, Sacramento, Santa Cruz and Los Angeles — have had the lowest success rate for placing individuals in permanent housing. Those counties saw 0.8%, 1.7%, 2% and 4.5%, respectively, of their total Roomkey clients transition to permanent housing.

Comparisons must be taken with a grain of salt, though, as many clients are still in the program. For example, San Bernardino County has seen one of the lowest rates of Roomkey beneficiaries returning to homelessness so far at 8%, but it also has the highest percentage of clients still in hotels with 74% of its 824 clients remaining in Roommkey units.

San Bernardino County secured 427 rooms, all of which remain occupied. About half the rooms were occupied by an individual and the other half by a couple or family.

Rodeway Inn & Suites in Indio, Calif. partnered with the state for Project Roomkey, an effort by the state to house individuals experiencing homelessness during the COVID-19 pandemic. VICKIE CONNOR/THE DESERT SUN

'Where did all that funding go?'

In some ways, Fournier got lucky amid the pandemic. He'd been staying with friends prior to a string of hospitalizations due to diabetic complications. After that, he was sent to a skilled nursing facility and then a board and care facility to recover. As he was set to leave, his nurse asked him where to, and he said, “I don’t know.”

A social worker at the facility sent him to meet with a housing caseworker who linked him to Project Roomkey.

While Fournier is one of thousands who remain in hotels awaiting a permanent placement — or eviction — other homeless Californians didn't snag a room at all.

Raymond Thompson, 65, who has been homeless for three months in Southern California, was told he qualified for Project Roomkey but wasn't able to secure a room before funding ran out.

“I signed up on July 12 and they told me to wait for a phone call that I never got," he said. "… Where did all that funding go?”

As he waited for the phone call, Thompson continued to sleep outside behind a gas station dumpster in Cathedral City. He would ride the bus in circles around town when it was too hot during the peak of the summer.

But on a day that hit 122 degrees, he ended up in a local hospital due to dehydration.

Now that desert temperatures are quickly dropping, Thompson expects to face months of cold nights as he curls up under blankets outside.

Rodeway Inn & Suites in Indio, Calif. partnered with the state for Project Roomkey, an effort by the state to house individuals experiencing homelessness during the COVID-19 pandemic. VICKIE CONNOR/THE DESERT SUN

Desert Sun reporter Nicole Hayden covers health and homelessness in California. She can be reached at Nicole.Hayden@desertsun.com or (760) 778-4623. Follow her on Twitter @Nicole_A_Hayden.

This story was produced as part of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 California Fellowship.

[This story was originally published by Desert Sun].